The Influence of National Culture on Commitment that Produce Behavioral Support for Change Initiatives

Saeed Hameed Aldulaimi1

1College of Administrative Sciences Applied Science University (ASU) - Bahrain Kingdom. |

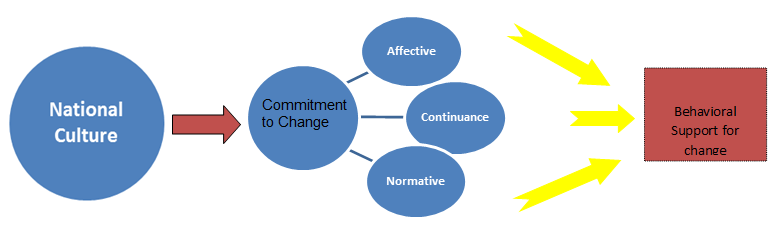

AbstractOrganizations progressively become innovative and recognize the environments that push for compliance within their internal environment and circumstances in the external environment. The rationale of this research is to discover the impact of national culture dimensions on commitment to organizational change initiatives. The current study review the previous studies to classify the aspects that impact organizational commitment and must be considered in managing change initiatives in organizations. This research assessed commitment by utilizing the Herscovitch and Meyer (2002) commitment to change scales to measure three components including affective, continuance, and normative commitment. National culture is measured utilizing the values survey module 2008 (Hofstede). The independent variable is national culture and the dependent variables are affective, continuance, and normative commitment. |

Licensed: |

|

Keywords: |

Funding: This study received no specific financial support. |

Competing Interests: The author declares that there are no conflicts of interests regarding the publication of this paper. |

1. Introduction

This exploration study will be conducted to investigate how the complex aspect of national culture variables influence the commitment to organizational change and how leadership can utilize the phenomena of culture to turn into a part of employee work life and consequently achieving organizational commitment to change. Revising the literature uncover there is no research exists on the influence of national culture on commitment to organizational change. The successful implementation of change initiative can be done through the commitment to change itself by attaching the individuals to the necessary actions for change (Erkutlu & Chafra, 2016). Organizational culture and commitment to change bring solutions to problem during the transitional era.in addition, there is a growing interest in research to investigate the role of employee commitment in organizational change situations (Aldulaimi & Sailan, 2012).

The rapid and rapid developments in our world and its associated changes have led to Concepts and events accelerated to influence business organizations, as well as influence on Freedom of movement of services and goods between different countries in a manner that calls for the return Consider the study of the administrative methods and practices practiced by the organizations and the impact thereof Raising performance and productivity levels within these organizations. On the other hand, both social and cultural factors have a significant impact on both organizations and individuals belonging to a country. The level of performance and quality of organization management is affected by a degree Significant in the social and cultural environment. The behaviour and performance of individuals within those organizations in society both inside and outside the organizations are working a reflection of the elements of that environment, so the culture of society plays a fundamental role in life organizations and individuals. But this impact on social and cultural factors necessarily varies depending on the nature of these organizations and the different individuals.

At the organizational level, there are internal factors related to the nature of the activity and the area in which it operates in each organization, as well as the level and style of management and leadership of these organizations and the quality of individuals Employees. These factors make organizations working in one society different among them, this difference is not only the level of performance or level of business results but also in the nature of the factors that make up the internal environment of the organization affected by the external environment Individually characteristics. This is what is meant by organizational culture or culture of the organization. These organizational culture is formed and this formation is reconfigured by its members who are in the same Time members of the community. So no change in cultural and social factors in the community necessarily affect the culture within the organization.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Culture

Culture (from the Latin cultura derived from colere, meaning "to cultivate") and the term “culture” refers to collective thinking of certain society as Hofstede mentioned (Aldulaimie, 2018). Culture has several meanings all derived from its Latin source, which refers to the tilling of the soil (Hofstedep, 1991).

Management scholars have pointed out that not all cultures fit all purposes, attitudes or people, and that these cultures are based on time by the dominant groups of the organization to suit them, and that what is appropriate to the institution at one stage is not necessarily appropriate forever. Ultimately, the culture is based on common constants, beliefs, customs, and written and unwritten rules that have been developed over time and are considered valid.

The concept of culture is one of the most widely accepted concepts, according to the different orientations of scholars and researchers who have studied the concept of culture. Although the use of the term culture is widely used in the media as well as in the academic language. This concept has been treated very superficially in the understanding. The knowledge and science group is the first to come to the mind of the reader or listener when the word "culture". Demorgon sees the term "culture" as the origin of Latin culture, which means the process of plowing the earth. In language, the word culture means care of the mind and care for human refinement.

During the 17th century, the concept of culture further expanded to address items made by humans versus those created by nature. The work, Of the Law of Nature and Nations, published in 1684 by the German philosopher Samuel Pufendorf, further labelled culture as the existence of things developed by humans in opposition to natural conditions. By the mid-18th century, culture was a common term used throughout Eastern Europe denoting key parts of social life as extensions of human activity that separate human from animal actions (Stephin, 2003).

Near the end of the 19th century the British anthropologist Sir Edward Burnett Tylor defined culture as "that complex whole which includes knowledge, belief, art, morals, law, custom and any other capabilities and habits acquired by man as a member of society." Tylor's definition includes three of the most important characteristics of culture: (1) Culture is acquired by people. (2) A person acquires culture as a member of society. (3) Culture is a complex whole. Tylor is considered representative of cultural evolutionism. In his works Primitive culture and Anthropology, he defined the context of scientific study of anthropology, based on the evolutionary theories of Charles Darwin. He believed that there was a functional basis for the development of society and religion, which he determined was universal (Cited in Sackmann (1991)).

The term “culture'' has its theoretical roots within social anthropology and was first used in a holistic way to describe the qualities of a human group that are passed from one generation to the next”. Coincidentally, the sociologist (Parsonsp, 1951) developed a theory of social action, and which he also called "structural functionalism." Parson's intention was to develop a total theory of social action (why people act as they do), his model explained human action as the result of four systems:

- the "behavioral system" of biological needs

- the "personality system" of an individual's characteristics affecting their functioning in the social world.

- the "social system" of patterns of units of social interaction, especially social status and role

- the "cultural system" of norms and values that regulate social action symbolically

In most western languages culture commonly mean ‘civilization’ or refinement of the mind and in particular the results of such refinement, like education, art and literature (Hofstedep, 1991). Hofstedep (1991) produced that people unavoidably carry several layers of mental programming within themselves, corresponding to different levels of culture for example

- National level : according to one’s country

- Regional , ethnic, religion, linguistic affiliation level

- Gender level

- Generation level

- Social class level

- Organisational or corporate level

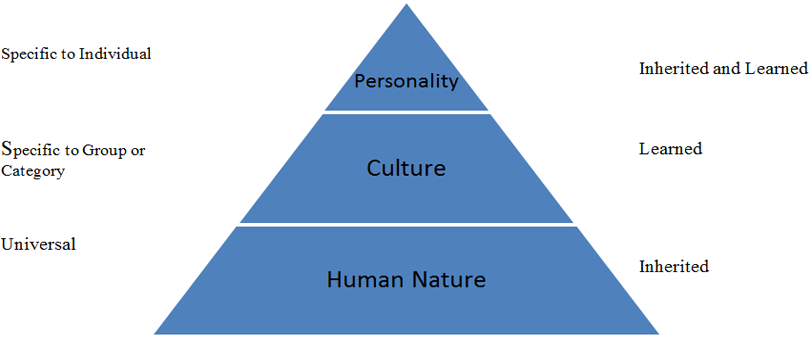

According to Hofstede “culture is the collective programming of the mind which distinguishes the members of one group or category of people from another”. Culture is learned not inherited; it derived from one’s social environment not from ones genes. Culture should be distinguished from human nature one side (the universal human being have in common or inherit), and from an individual personality on the other side (the unique personal set of mental programs which not share with the others). Figure 1 illustrates the position of culture between human nature and personality.

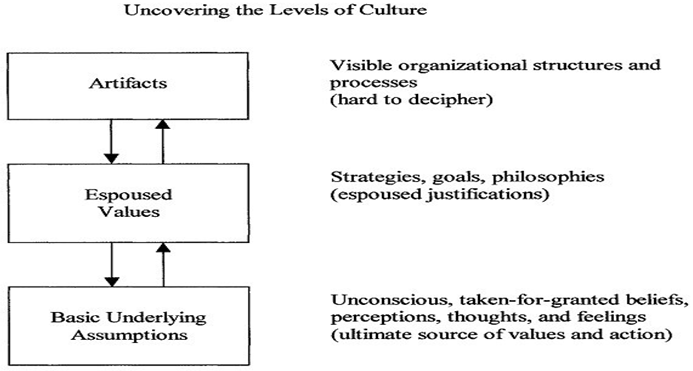

Toward the end of the 20th century, after considerable research, Schein (1992) produced a greatly simplified definition of culture. He defined culture as, "A set of shared, taken-for-granted implicit assumptions that a group holds and that determines how it perceives, thinks about, and reacts to its various environments" (p. 7). Furthermore, Scheine (1985) classified the culture to three levels:

- Behaviors and artifacts: this is the most manifest level of culture, consisting of the constructed physical and social environment of an organization.

- Values: being less visible than are behaviors and artifacts, the constituents of this level of culture provide the underlying meanings.

Basic assumptions: these represent an unconscious level of culture, at which the underlying values. By this definition, basic assumptions are also the most difficult to relearn and change.

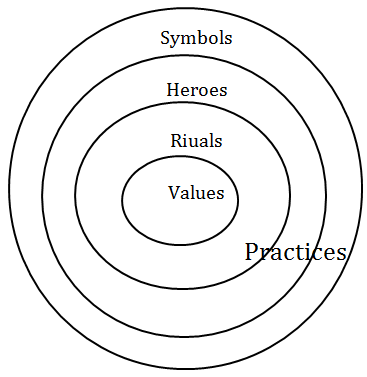

Consistent with other researchers (Kotter & Heskett, 1992) say culture refers to “values that are shared by the people in a group and that tend to persist over time even when group membership changes” (p. 4). Hofstede suggested four manifestations to describe the culture symbols,heroes,riuals and values Figure 3.

2.2. The Significance of Culture

Hofstede wondering why so many solutions do not work or cannot be implemented is because differences in thinking among the partners have been ignored. Understanding such differences is at least as essential as understanding the technical factors. Hofstedep (1991). Researcher to this importance have study the impact of organizational culture on total quality management (Daniel & Christopher, 2005) on organizational performance (Deal & Kennedy, 1982; Denison, 1990; Kotter & Heskett, 1992) “it has been suggested that organizational culture affects such outcomes as productivity, performance, commitment, self-confidence, and ethical behaviour”. Moreover, Denison (1990) identify four cultural traits of cultural effectiveness as below:

- Involvement is a cultural trait which is positively related to effectiveness.

- Consistency is a cultural trait that is positively related to effectiveness.

- Adaptability, or the capacity for internal change in response to external conditions, is a cultural trait that is positively related to effectiveness.

- Sense of mission or long term vision is a cultural trait that is positively related to effectiveness.

2.3. National Culture

The following analysis of literature begins with a review of Hofstede’s interpretation of culture, followed by his theory on national culture, as introduced in the Preceding chapter. This will provide a base for the remainder of the literature review. The work of Hofstedep (1980) stands out for the connection of design activities to national culture and organizational forms. His comprehensive study of over 100,000 questionnaires in 66 countries is the basis for a noteworthy theoretical explanation of the influence of national culture on organizations. Hofstede constructed his framework on a review of sociological and anthropological theories and work including Geertz (1973); Kluckhohn (1951); Kluckhohn (1962); Parsonsp (1951); Parsons and Shils (1951) and Weber (1946).

Hofstede (1991) showed that perceptions of organization culture may be affected by nationality and demographic characteristics.

Additionally, this literature review provides a brief overview of the four major competing theories on which Hofstede relied when formulating his theory on national culture Table 1 and the three other theories looked at by Hofstede but not considered to any great extent, Table 1.

The values, trends and customs of the society in which the organization is located are transferred from society to the organization through workers, which contributes to the formation of the culture of the organization. This culture is influenced by a number of social variables such as: political system, economic system, cultural and social conditions, environment Internationalization and globalization. All of these affect the organization's strategy, objectives and standards, and its foundations. In order for the organization to be accepted and legislated, its strategies must be compatible with the culture of society.

| Researcher | Theory | Year established |

Components |

| Hofstedep (1980) | National culture dimensions | 1980 |

Five cultural dimensions: 1. individualism versus collectivism 2. power distance 3. uncertainty avoidance 4. masculinity versus femininity 5. long-term versus short-term orientation |

| Inkeles and Levinson (1969) | Standard analytical issues |

1969 |

Three standard analytical issues: 1. relation to authority 2. conception of self 3. primary dilemmas or conflicts, and ways of dealing with them |

| Kluckhohns and Strodtbeck (1961) | Value orientations |

1961 |

Six value orientations: 1. human nature orientation; 2. man-nature (-super nature) orientation; 3. time orientation; 4. activity orientation; 5. relational orientation; 6. human nature orientation |

| Parsons and Shils (1951) | Pattern variables | 1951 |

Five pattern variables: 1. affectivity vs. affectivity neutral; 2. self-orientation vs. collectivityorientation; 3. universalism versus particularism; 4. ascription versus achievement; 5. diffuseness versus specificity |

| Source: Hofstedep (1991). |

Hofstede correlated the construct of culture to the construct of “mental programming” (1980, p. 13) of the brain. A construct is a way of representing observed events therefore, it is subject to a level of subjectivity by the definer (Hofstedep & Hofstede, 2005). Further, a construct does not exist; rather, it is a product of our imagination and is supposed to help us understand something (Hofstede). According to Hofstede, the construct of “mental programs” (1980, p. 13), which he also referred to as “software of the mind” (2005) does not mean that someone is programmed like a machine or computer; rather, it means that the way someone reacts can be predictable given the person’s past and the social environments in which he or she was raised. Mental programs are partly shared with the people who live or lived within the same social environment where it was learned, and are partly unique to the individual (Hofstedep & Hofstede, 2005). Hofstedep (1980) defined three levels of mental programs:

1. Universal—is shared by all, or almost all, mankind is the biological operating system of the human body includes a range of expressive behaviours such as laughing and weeping and associative and aggressive behaviours. (p. 15)

2. Collective—Is shared by some, but not with all other people, it is common to people belonging to a certain group or category, but different among people belonging to other groups or categories, it includes the language, the deference we show to our elders, the physical distance from other people we maintain in order to feel comfortable, the way we perceive general human activities, and the ceremonials surrounding them. (p. 15)

3. Individual—No two people are programmed exactly alike, even if they are identical twins raised together. This is the level of individual personality, and provides for a wide range of alternate behaviors within the same collective culture. (p. 16)

According to Hofstedep (1980) it is difficult to distinguish between the individual level and the other two levels. The universal level is almost entirely inherited, meaning universal mental programs are genetically inherited. In contrast, the collective mental programs are mostly learned, which means they are something we share with other people and have no genetic basis.

Hofstedee (2001) developed the following definition for culture: “Culture is defined as collective programming of the mind that distinguishes the members of one group or category of people from another” [where] the “mind” refers to how one thinks, feels and acts with consequences for beliefs, attitudes, and skills” (pp. 9–10).

In looking at nations, Hofstede used the word culture in the same way that it is used to refer to groups of people such as organizations, ethnic groups, professions, gender groups, or families, but at a society level. Hofstede defined society as a “social system characterized by the highest level of self-sufficiency in relations to its environment” (p.10), meaning groups within a society tend to have a certain level of interdependence. At the center of the social system are societal norms consisting of value systems or, as Hofstedep (1980) called it, mental programs that are shared by the majority of a population. The norms are based on a variety of ecological factors (geographic, economic, demographic, genetic/hygienic, historical, technological, and urbanization) that affect the physical environment and lead to the development of culture patterns in such areas as family, education systems, politics, and legislation (Hofstede).

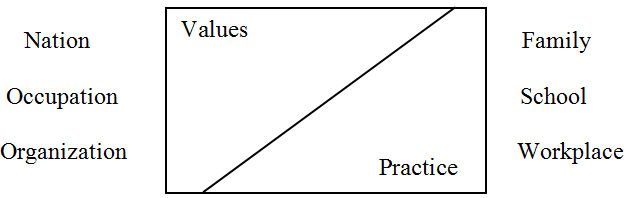

Hofstedee (2001) illustrate that at the national level cultural differences reside mostly in values, less in practice rather in organizational level the cultural differences reside mostly in practice, less in values. Figure 4

Hofstede’s Cultural Dimensions for National Culture

Hofstedep (1991) suggested that culture at a national level can be classified according to five dimensions: “power distance uncertainty avoidance individualism versus collectivism, masculinity versus femininity [and] long-term versus short-term orientation” (p. 29). The first four dimensions were conceived from the results of an attitude survey administered to 116,000 IBM employees in 40 different countries in 1968 and 1973 (Hofstedep, 1980). The fifth dimension was added later through the joint efforts of Hofstede and Bond (1988) where they developed and administered the Chinese Value Survey to 100 students in 23 countries. The resulting fifth dimension was originally referred to as “Confucian Dynamism to show that it deals with a choice from Confucius’ ideas and that its positive pole reflects a dynamic, future oriented mentality, whereas its negative pole reflects a more static, radiation oriented mentality” (Hofstede and Bond). Later, the dimension was renamed “long-term versus short-term orientation” (Hofstedee, 2001). The five national culture dimensions proposed by Hofstede are:

1. Power distance which is related to “the different solutions to the basic problem of human inequality” (2001, p. 29). It is the “extent to which the less powerful members of institutions and organizations within a country expect and accept that power is distributed unequally” (2005, p. 46). Power distance “is described based on the value systems of the less powerful members. The way power is distributed is explained from the behaviour of the more powerful members, the leaders rather than those led” (2005, p. 46).

2. Individualism versus collectivism which is “related to the integration of individuals into primary groups” (2001, p. 29). Individualism refer to what extent the ties between individuals are loose: everyone care about himself and his family. Collectivism refer to the binds ties people are strong, person live for others. (2005, p. 76)

3. “Masculinity versus femininity which is related to the division of emotional roles between men and women” (2001, p. 29). A society is called masculine when emotional gender roles are clearly distinct: men are supposed to be assertive, tough, and focused on material success, whereas women are supposed to be more modest, tender, and concerned with the quality of life. A society is called feminine when emotional gender roles overlap: both men and women are supposed to be modest, tender, and concerned with the quality of life. (2005, p. 120)

4. “Uncertainty avoidance which is related to the level of stress in a society in the face of an unknown future” (2001, p. 29). Further, Uncertainty avoidance [is] the extent to which the members of a culture feel threatened by ambiguous or unknown situations. This feeling is, among other things, expressed through nervous stress and in a need for predictability: a need for written and unwritten rules. (2005, p. 167)

5. “Long-term versus short-term orientation which is related to the choice of focus for people’s efforts: the future or the present” (2001, p. 29).

Long-term orientation (LTO) stands for “the fostering of virtues oriented toward future rewards—in particular, perseverance and thrift”. Its in particular, respect for tradition, preservation of “face,” and fulfilling social obligations. (2005, p. 210)

Schwartz (1999) develop a model to study the national culture. Also, Trompennaars and Hampden-Turner (1998) proposed seven dimensions for examining a culture which it is Universalism particulism, individualism and communitarianism inner-directed vs. outer-directed, time as sequence vs. time as synchronization, achieved status vs. ascribed status and equality vs. hierarchy.

2.4. Organizational Commitment

The term “commitment” can be referred to “as the willingness of social actors to give their energy and loyalty to a social system or an effective attachment to an organization apart from the purely instrumental worth of the relationship” (Buchanan, 1974). By 1983, Morrow had cited over 25 concepts and measures pertaining to organizational commitment, such as participating in a union, exercising a Protestant work ethic, being involved in work, and central life interest. Commitment can be viewed from two perspectives, the employee and the employer perspective. From the employer perspective, commitment employee benefit the organization by improving the efficiency and effectiveness of the organization in terms of increased performance and reduce employee turnover and absenteeism (Mowday, Porter, & Steers, 1982). From the employee perspective, commitment employee gain financial and non-financial benefits such as monetary gains and job satisfaction (Meyerp & Allen, 1997). Allen and Meyer (1990) proposed a three-component model of commitment, which integrates these various conceptualizations. They suggested that there are three types of commitment: (1) Affective; (2) Continuance; and (3) Normative.

The affective commitment discusses employees’ emotional attachment to the organization. The continuance commitment states the costs the employees associate with leaving the organization. The normative commitment discusses employees’ feelings of obligation to remain with the organization. Organizational commitment has also been found to be positively associated with higher work motivation, greater organizational citizenship, as well as higher job performance (Meyere, Stanley, Herscovitch, & Topolnytsky, 2002).

Commitment Definitions

Although Organizational Commitment has been defined in several different ways, a common theme is a linking or bonding phenomenon between the employee and the employing organization. The employee’s motivations behind the bonding process have been addressed in two general ways. Some researchers have adopted a “calculative” perspective and some an “attitudinal” perspective. The calculative perspective evolved out of the cost reward (Gouldner, 1960). This approach suggested that employees calculate or weigh the rewards they receive from the organization against the costs associated with organizational membership. If individuals perceive a good and fair balance between the rewards (e.g.,salary, benefits, pension, office space, parking) and costs (e.g., effort, stress, time), they tend to be committed to the organization (Becker, 1960; Salancik, 1977). Under this definition, committed employees generally align their values with those of the organization, behave in ways that aid the success of the organization, and continue their employment over time with the organization. The inclusion of the “intent to stay” element has sparked debate in the literature.

The word "commitment" returns to the verb commit, and it is necessary, in the sense that it is proven and sustained, and it is committed to money and work then became duty. The organizational commitment of the behavioral concepts that took dimensions and trends have been wide. This study define different ways to describe the committed individual who is keen to show specific behavior models such as the defence of the organization and the sense of pride and pride of belonging to it and the desire to stay there for the longest period, as well it is characterized by high levels of the behavior of the distinctive role that is directed towards the desired performance. Mcshane and Glinow (2007) points out that commitment is the extra sense of predict work and defining the as the following:

1 - Affective commitment which refers to the emotional feeling towards the organization. The emotional obligation is described as the positive desire to act in a specific way.

2-Normative commitment it reflects a sense of commitment to the ongoing work as well as a sense of commitment to and commitment to the workers meet the Organization.

3-Continuous commitment It refers to the costs associated with the organization and those who have an initial link in the organization they can dispense with it.

An organizational obligation is defined as the relative strength of a person's self-identification as an employee of the organization

The organization in which it operates and the importance of organizational commitment as a largely conceptual concept. The widespread prevalence of variation in compliance levels can explain variance in many variables. in general subordinates with high commitment connect their attitudes with the values of their organizations and goals and show committed to staying in it.

The affective commitment measure reflects the organization's adherence to the measure of continuous compliance reflecting the individual's perception of the returns and costs of survival in the organization, and the standard compliance measure is reflected commitment on the basis of the individual's belief that he is morally committed to stay in the organization,

Mcshane and Glinow (2007) has identified some points to build organizational commitment as follows:-

1 - Justice and support: - The emotional commitment in organizations requires the commitment of human values.

2 - shared values: - The mental commitment will be high if I think workers share their values with values

The Organization, which would be satisfied with their stay in the Organization.

3 - Trust: - means the placement of faith in another person or group by employees who have an obligation

High in the organization that generates confidence in their leadership.

4 - Organizational Integrity: - Increasing the emotional commitment in the knowledge of the worker past, present and future

The company and thus the direction of loyalty will increase.

5. Workers' requirements: - To increase emotional commitment, social relations within the organization should be strengthened

The worker then feels that he is part of the organization when he participates in decision-making.

In many organizations, the rewards associated with calculative commitment are finite. Perhaps this is why most of the literature has focused on attitudinal commitment. Along those lines, Mowday et al. (1982) define organization commitment as “the relative strength of an individual's identification with, and involvement in, a particular organization” (p. 27). Mowday et al. (1982) defined organizational commitment as “the relative strength of an individual’s identification with and involvement in a particular organization” (p.226). In general, organizational commitment is a “multidimensional construct” (Morrow, 1993) that has the potential to predict organizational outcomes such as performance, turnover, absenteeism, tenure, and organizational goals” (Meyerp & Allen, 1997). According to (Meyerp & Allen, 1997) “commitment employee is one who stays with the organization through thick and thin, attends work regularly puts in a full day (and maybe more), protect company assets, shares company goals, and so on “ (p.3)

2.5. Commitment to Change

Commitment is one of the most important factors to support for change initiatives. Meyere and Herscovitch (2001) stated that the three component model should be applicable to the study of other forms of workplace commitment. They argue that these mind-sets can be measured and shown to be discernible from one another, and from mind-sets relating to other workplace commitments.

Herscovitch and Meyer’s Model of Commitment to Organizational Change:

Herscovitch and Meyer (2002) proposed that commitment could take different forms and have different implications. They developed six item measures of affective (AC), normative (NC) and continuance (CC) commitment to a change. However, only AC and NC correlated positively with cooperation and championing – CC correlated negatively AC, NC and CC have all been found to relate negatively with turnover intentions and turnover, but only AC and NC commitment relate positively to citizenship behavior (see Meyer, Stanley, Herscovitch, and Topolnytsky (2002)). If there is one generalization we can make about leadership and change it is this: No change can occur without willing and committed followers.

2.6. National Culture and Organizational Commitment

The organization's culture is the key to the success of any organization. It plays a large role in the cohesion of individuals and preservation on the identity of the group, it is an effective tool in directing the behavior of employees and help them to perform their work in a better way based on informal rules and regulations. The culture for any organization built and designed based on the culture of the society. Actually, it is the real reflection of the society culture.

The culture of the organization affects the degree of commitment and discipline shown by members of the organization, and indicates commitment. In addition, the degree to which members of the organization are prepared to make efforts and loyalty and to demonstrate their belonging to the organization and to achieve objectives.

In other words, culture creates conditions in the organization that make individuals either ready or not are prepared to adhere to the Organization's goals in order to reach a general state of satisfaction or dissatisfaction. Strong culture can support the willingness of individuals to give a great deal of commitment and loyalty to the organization, through many factors can increase the loyalty of employees to the organization and who have a strong incentive to adopt a culture. The organization then has a strong incentive to embrace the organization's culture as a way of life and can help organizational culture, in increasing the organizational commitment of members.

Black (1999) examine the relationship between national culture and high commitment management (HCM). He further founds that the adoption of certain individual HCM practices is more closely associated with superior employee performance in countries with certain cultural characteristics than in others. Janet, Susan, and Paul (2008) in their research on employee commitment to organizational change they found that vision, member-leader relationship quality, motivation, and independent all influence commitment to change. Notably, affective commitment, which in turn influences employee perceptions about improved performance, implementation success, and individual learning regarding the change, had the greatest impact.

To summarize, it has been shown that there can be no effective change without an integration and overlap relationship with the culture. We find that the values, beliefs, rituals and behavior patterns affect the change management strategies application within the organization, where we find that these strategies have a profound impact on the behavior of individuals and values and beliefs and some other cultural elements making them more successful and adaptive to these new and ongoing changes. It also shows the role that organizational culture plays in influencing organizational change management strategies. This is due to the strong correlation between organizational culture and change management.3. Conclusions

This study concentrates to examination the literature that dealt with the relationship between national culture and commitment to organizational change in order to investigate the influence of the national culture on the attitudes of employees toward change initiatives which deemed necessary in the work environment which distinguished by variety and competitiveness. Consequently this study will submit approaches which able to assess and measure the influence of national culture on commitment to organizational change. Yet the importance of managing change is reflected in the fact that good management of change hurts to reduce technical and humanitarian problems which organizations are living all the time, and thus represents change and good management to keep pace with changes as one of the assumptions on which they are based organization for reasons of continuity.

The conceptual framework focused on presenting the exploratory study of national culture on organizational commitment to change with an emphasis on any impact the relationships between these two variables may have had on organizations and their stakeholders. Figure 5 presents and illustrate the study variables.

Figure-5. The conceptual framework of the study.

The success of the organization requires the intervention of several factors, and organizational culture is one of the key determinants of success business institutions are superior, as organizational culture is a system of values and common rules among members of the organization which the organization adopts to guide its actions and practices.

This is illustrated by linking the dimensions of culture. Organizational and change management strategies adopted at the individual, team and enterprise level as a whole. So the whole planning or implementing change management strategies ensures that it succeeds by knowing the prevailing behavioral construct that expresses the prevailing organizational culture and the exclusion of this aspect makes the management of change far from implementation and achieving the objectives in founder.References

Aldulaimi, S., & Sailan, S. (2012). The national values impact on organizational change in public organizations in Qatar. International Journal of Business and Management, 7(1), 182-191.

Aldulaimie, S. H. (2018). The influence of national culture on commitment that produce behavioral support for change initiatives. International Journal of Applied Economics, Finance and Accounting, 3(2), 64-73.

Allen, N., & Meyer, J. (1990). The measurement and antecedents of affective, normative and continuance commitment to the organization. Journal of Occupational Psychology, 63(1), 1-18.

Becker, H. S. (1960). Notes on the concept of commitment. American Journal of Sociology, 66(1), 32-42.

Black, T. R. (1999). Doing quantitative research in the social sciences: An integrated approach to research design, measurement and statistics: Sage.

Buchanan, B. (1974). Building organiza-tional commitment: The socialization of managers in work organizations. Administrative Science Quarterly, 19(4), 533-546.

Daniel, I. P., & Christopher, M. M. (2005). The relationship between total quality management practices and organizational culture. International Journal of Operations & Production Management, 25(1), 1101-1122. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1108/01443570510626916 .

Deal, T. E., & Kennedy, A. A. (1982). Corporate cultures. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley.

Denison, D. R. (1990). Corporate culture and organizational effectiveness. New York: John Wiley & Sons.

Erkutlu, H., & Chafra, J. (2016). Value congruence and commitment to change in healthcare organizations. Journal of Advances in Management Research, 13(3), 316-333.

Geertz, C. (1973). The interpretation of culture: Selected essays. New York: Basic Book.

Gouldner, A. W. (1960). The norm of reciprocity: A preliminary statement. American Sociological Review, 25(2), 161-178.

Herscovitch, L., & Meyer, J. P. (2002). Commitment to organizational change: Exten-sion of a three-component model. Journal of Applied Psychology, 87(3), 474–487.

Hofstede, G., & Bond, M. H. (1988). The confucius connection: From cultural roots to economic growth. Organizational Dynamics, 16(4), 5-21. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/0090-2616(88)90009-5 .

Hofstedee, G. (2001). Culture’s consequences: Comparing values, behaviors, institutions and organizations across nations. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage.

Hofstedep, G. (1980). Cultures consequences: International differences in work-related values. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage Publications.

Hofstedep, G. (1991). Cultures and organizations: Software of the mind. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Hofstedep, G., & Hofstede, G. J. (2005). Cultures and organizations: Software of the mind: Intercultural cooperation and its importance for survival. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Inkeles, A., & Levinson, D. J. (1969). National character: The study of modal personality and sociocultural systems. In G. Lindzey & E. Aronson (Eds.), The handbook of social psychology IV (pp. 418-506). New York: McGraw-Hill.

Janet, T. P., Susan, C., & Paul, B. (2008). Want to, need to, ought to: Employee commitment to organizational change. Journal of Organizational Change Management, 21(1), 32-52. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1108/09534810810847020 .

Kluckhohn, C. (1951). Values and value-orientations in the theory of action: An exploration in definition and classification. In Parsons, T., Shils, E.A. (Eds), Toward a General Theory of Action. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Kluckhohn, C. (1962). Universal categories of culture. In Tax, S. (Eds), Anthropology Today. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Kluckhohns, F. R., & Strodtbeck, F. L. (1961). Variations in value orientations. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press.

Kotter, J. P., & Heskett, J. L. (1992). Corporate culture and performance. New York: Free Press, Macmillan.

Mcshane, S. L., & Glinow, V. (2007). Organizational Behavior. Australia: Higher Education.

Meyer, J. P., Stanley, D. J., Herscovitch, L., & Topolnytsky, L. (2002). Affective, continuance, and normative commitment to the organization: A meta-analysis of antecedents, correlates, and consequences. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 61(1), 20-52. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1006/jvbe.2001.1842 .

Meyere, J. P., & Herscovitch, L. (2001). Commitment in the workplace: Toward a general model. Human Resource Management Review, 11(3), 299–326.

Meyere, J. P., Stanley, D. J., Herscovitch, L., & Topolnytsky, L. (2002). Affective, continuance and normative commitment to the organization: A meta-analysis of antecedents, correlates, and consequences. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 61(1), 20-52.

Meyerp, J., & Allen, N. (1997). Commitment in the workplace: Theory, research and application. London: Sage.

Morrow, P. C. (1993). The theory and measurement of work commitment. Greenwich, Connecticut: JAI Press Inc.

Mowday, R. T., Porter, L. W., & Steers, R. M. (1982). Employee-organization linkages: The psychology of commitment, absenteeism, and turnover. New York: Academic Press.

Parsons, T., & Shils, E. A. (1951). Values, motives, and systems of action. Toward a General Theory of Action, 33, 247-275.

Parsonsp, T. (1951). Toward a general theory of action. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Sackmann, S. (1991). Cultural knowledge in organizations: Exploring the collective mind. Newbury, CA: Sage Publications.

Salancik, G. (1977). Commitment and the control of organizational behaviour and belief. In B. Staw and G. Salancik (Eds.), New directions in organizational behaviour. Chicago: St. Clair Press.

Schein, E. (1992). Organizational culture and leadership (2nd ed.). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Scheine, E. H. (1985). Organizational culture and leadership (1st ed.). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Schwartz, S. H. (1999). A theory of cultural values and some implications for work. Review of Economics and Business, 21(2), 73-92.

Stephin, V. S. (2003). Culture. Russian Studies in Philosophy, 41(4), 9-25.

Trompennaars, F., & Hampden-Turner, C. (1998). Riding the waves of culture: Understanding human-values? Journal of Social Issues, 50(4), 19-46.

Weber, M. (1946). Bureaucracy. In Gerth, H.H., Mills, C.W. (Eds), From Max Weber: Essays in Sociology. New York: Oxford University Press.