Tax Reforms and Nigeria’s Economic Stability

Wilson E. Herbert1*

Innocent Augustine Nwarogu2

Caritas Chimere Nwabueze3

1Dept. of Banking and Finance, Faculty of Management Sciences, Federal University, Otuoke, Bayelsa State, Nigeria. |

AbstractTax reforms represent a fundamental strategy of a country’s fiscal consolidation and governance. In this study, we examine the effect of tax reforms on economic stability of Nigeria over a 16-year period, 2000-2015. The study used a transformed econometric linear model to assess how and to what extent tax reforms support economic stability, proxied by gross domestic product (GDP). We identify company income tax and petroleum profit tax as key levers to Nigeria’s fiscal stability. However, while VAT reforms have positive relationship with economic stability, the effect is negligible. Although every tax reform has a positive effect on revenue accretion, greater attention should be paid to those components of fiscal reform that have prospective significant positive consequences on economic growth and stability as against a blanket reform proposal that includes aspects with a potential negative outcome. A decision-analytic prognosis about the governance architecture of Nigeria’s tax ecosystem suggests (a) that effective and efficient tax administration, as a component of fiscal policy, is central to a country’s fiscal management, macroeconomic growth and stability, and (b) an urgent improvement to validate the certainty and administrative integrity and transparency of the tax regime. In general, macroeconomic reforms, more so in SSA countries, must develop targeted and industry-focused fiscal initiatives and programmes that will stimulate productivity, competitiveness, efficiency, employment growth |

Licensed: |

|

Keywords: |

|

| (* Corresponding Author) |

Funding: This study received no special financial support. |

Competing Interests: The authors declare that they have no competing interests. |

1. Introduction

If men were angels, no government would be necessary. If angels were to govern men, neither external nor internal controls on government would be necessary. The Federalist No. 51, In Rossiter (1961).

Were taxation not a mandatory civic responsibility, there would be little or no incentive for economic entities (individuals and businesses) to voluntarily part with a portion of their incomes to the state. There are at least two conceptual logics that underpin this inertia. First, the natural aversion to tax payment provides a conceptual raison d’être of taxation as a compulsory contribution to government revenue from the earnings (income or profit) or wealth of economic entities. As an obligatory imbursement, there is a natural aversion to such compulsory levies or parting with one’s hard-earned income or wealth, especially in states where the benefits of such heavy demands are not visible or felt by the citizens. Second, in developing countries, citizens’ apathy towards taxation is familiar, owing to a combination of factors, chief of which are (a) lack of transparency and accountability by governments and their agencies, and (b) the bureaucratic inertia by various tiers of government, especially the revenue-generating agencies. Yet, tax imposition is grounded in the nature of State as the provider of public goods and services. The inherent obligation of provision of public goods and services compels government spending, and taxes are a sure way to finance these, and a sure way to get citizen participation in their funding. Taxation is therefore seen as an inherent power of the state to secure the funds needed to meet its social obligations. Apart from being an essential fiscal policy tool and one of the primary sources of public revenue across the world, research, such as Nwaorgu, Herbert, and Onyilo (2016) shows that the interaction effects of taxation play a pivotal role in the economy.

Consequently, tax reform is a fundamental fiscal policy strategy designed to enhance tax administration. Tax reform is a two-way process that necessitates changing the way taxes are collected and managed by government with a view to improving national income and gross domestic product (GDP), and providing economic and social benefits to the citizenry. For example, low tax revenue in most developing countries has been ascribed to inefficient tax administration, which may be a euphemism for corruption and/or distrust in tax administration and inefficient utilisation of tax revenue (Bird, 2015). The upshot is negative perception of taxpayers towards compliance. The suggestion therefore that inefficient tax administration with the resultant low tax revenue can be ameliorated through tax administration reforms underscores the need for this study.

The cliché that death and tax are two inevitabilities in the western world is one that that has not resonated across Sub-Saharan African (SSA) countries. While death is a universal certainty, there is no certitude about tax in SSA. The general presumption is that the wealthy in SSA not only avoid but corruptly evade taxes. The former is legitimate and logical on the premise that human beings are naturally averse to any imposition. As such, taxable entities try to explore and exploit every legitimate means to minimize current or future tax liabilities or shelter income from taxes using a variety of tax loopholes. In SSA countries, wealthy individuals and businesses are not only able to leverage off their web of political connectedness and means not covered or intended by law, but have consistently used these to corruptly engage in tax evasion.

While tax is perceived as a civic responsibility in all societies, however, in SSA, ordinary citizens will probably achieve consensus on no other matter than their common resentment of taxation. It is simply difficult to persuade private citizens (including the informal sector businesses) to voluntarily pay taxes. The underlying general question is: ‘Why do we have to pay taxes when Government is grossly impervious to such needs of the common man as electricity, water, road, education, and healthcare?’ That the typical Nigerian elite is a mini government of sorts – providing his/her own water (through sunk boreholes), electricity (through generators), education (through private basic and post-basic educational institutions), healthcare (through private procurement of medical care), and even private road construction (repairing roads and bridges, especially in their communities) – is not just a social media cliché but actually has been the reality in Nigeria. Most informal sector operators - hairdressers, welders, tyre vulcanizing machine operators, market traders, and small telecom and IT operators – cannot depend on epileptic public supply of electricity and water. Mundane things like public conveniences do not exist; where they are found, they are privately provided and maintained with usage costs. The involvement of private citizens in the provision of these services makes them beyond the reach of people, majority of whom are already ravaged by poverty, diseases and other indices of destitution and deprivation. These are strong emotive arguments which do not resonate in advanced and dynamic emerging economies of Asia. Therefore, the private procurement of rudimentary developmental infrastructure of the kinds just mentioned and the gross failure of government at all levels in this regard is the leverage ordinary citizens have against taxation. In fact, were PAYE (pay as you earn) not deducted at source, voluntary compliance thereof would be ineffectual. Anecdotal evidence and personal experience confirm that many employers deduct taxes and other levies at source but perennially fail to remit same to the appropriate tax authorities. The failure to bring delinquent employers to provide fully reconcilable accounts of such deducted government monies, held and spent by the employers, is traceable to the corrupt collusive tendencies of the tax authorities.

Yet, taxation is a key source of sustainable revenue for any economy as well as an indicator of economic performance. As such, the performance of taxation in propelling the revenue base of Government is immensely important to national development. In contrast with other sources of revenue, especially oil revenue, tax revenues are relatively predictable, thus enabling governments to plan with a greater degree of certainty than when relying majorly on natural resources. According to the International Monetary Fund (IMF) (2018) regional economic outlook, Nigeria’s tax to GDP ratio of 5.9 percent is below that of other large SSA economies. Africa’s most-populous nation and largest economy, with a population of about 200 million people, has the lowest tax-to-GDP ratio among SSA countries, compared to 24.7 percent for South Africa, according to the IMF, and about a quarter of the average percentage in the world. It is common knowledge that domestic revenue mobilization is one of the most pressing policy challenges facing Nigeria and other SSA economies. Therefore, reforms hold considerable potential to enhance collection of higher taxes. Structural reforms are very critical in finding the right balance for a country and economy. In particular, the transactional opaqueness of Nigeria’s petroleum industry means that the tax revenue collectible from the industry is corruptly understated. Not just the petroleum industry, all sectors of the Nigerian economy are in dire need of reforms to usher in greater revenues, and inject better governance through transparency and accountability in private and public sectors.

Tax reforms represent a fundamental strategy in improving the effectiveness of a country’s tax administration. That tax administration does not function optimally in many countries resulting in distortion of the intention of tax laws (Pellechio & Tanzi, 1995) is an implicit acknowledgement of organizational failure in the tax administration systems of many countries. Thus, for taxation to achieve its desired effect on resource allocation, distribution of income, and macroeconomic stability and growth, tax administration must function effectively and efficiently. Tax reforms are warranted for the following reasons: (a) when there is an exigency to modernize tax administration as part of a broad fiscal reform strategy in response to observed deficiency, inefficiency and ineffectiveness in the tax system; (b) as a response to the demands of a growing economy, in which an expansion of the tax net is necessary to incorporate hitherto uncaptured tax payers, for example, the growing number of informal sector players; and (c) when the imperatives of modern information and communications technology (ICT) and applications as well as changes in macroeconomic policies and legislation compel fiscal reforms, for example, to complement economic, trade and investment policies (See also, Silvani and Baer (1997). The common thread in most countries’ tax reform strategies is to enhance tax administration by addressing observed lapses in the tax collection system. This involves simplifying the tax collection/payment process, promoting voluntary taxpayer compliance, and adopting a logical sequence of procedures for efficiently identifying and managing noncompliance (Pellechio & Tanzi, 1995). This process should broaden the tax net to ensure that people and businesses outside the existing tax net are brought in, especially those operating in the informal sector of the economy.

Without equivocation, tax administration and tax policies in most SSA countries are fraught with abysmal performance and inefficiency occasioned by fraud and distrust in the entire political and economic systems accentuated by corruption and inept political and economic leadership. The result is citizen apathy towards what should naturally be a civic responsibility. Democratic governance is associated with social participation, which is comprised of actions and attitudes of citizens. Good governance plays an important part in influencing citizens’ level of civic mindedness through altruistic provision of efficient public services and infrastructure such as schools, healthcare delivery services and social safety net programmes. The outcome of poor tax policy and inefficient tax administration is low income generation and even the little that is generated is depleted by the mighty filthy hands of opportunism and corruption. In addition to using tax administration reforms to address the challenge of perennial lower tax revenue as canvassed by Taliercio (2004); Ogbonna and Ebimobowei (2012); Aminu and Eluwa (2014) and Nwaorgu et al. (2016) we submit that an effective and efficient tax administration reform is a potential catalyst for immediate attenuation of opportunistic proclivity of a corrupt tax bureaucracy. Major tax administration reforms have occurred in a number of developed countries, such as Canada, France, Germany, Japan, Spain, United Kingdom and USA, and developing countries, such as the Eastern European countries, Russia, China, and other economies in transition. In 2000, for example, Germany implemented a tax reform programme that professionalized the tax administration system which resulted in a dramatic advancement in tax collection (OECD, 2009). Equally, the experience of Spain affirms the hypothesis that a more efficient tax administration leads to more revenue generation. Specifically, enforcement, prosecution and tax auditing in Spain yielded an increase in the number of taxpayers from 1.7 million in 1988 to 2.8 million in 1991 (Hogue, Hassel, Olsson, Sabbe, & Ott, 2000).

Nigeria’s overdependence on oil revenue makes her a good candidate for tax administration reforms. The urgency of modernizing Nigeria’s tax administration (and other fiscal) systems is premised on the realization that the country is rated one of the lowest Tax/GDP ratios in the world. This much was loudly echoed by Nigeria’s former Minister of Finance, Kemi Adeosun, at the 2017 Spring Meetings of the IMF-World Bank in Washington DC, USA. Fielding questions on the side-lines of the said meetings, the Minister viewed the situation as unacceptable, stressing that the government was intent on achieving the objective of increasing non-oil revenue by encouraging companies and individuals to pay taxes which will help grow the country’s GDP, improve its revenue to debt ratio and enhance its ability to fund budgeted projects and get the economy back on track. With an unacceptably low level of non-oil revenue, driven chiefly by tax administration failure impelling low collection of tax revenue, the ex-Minister acknowledged that the country must do something fundamental about its revenue improvement. Tax administration reform offers advantages of three kinds. First, in relation to monolithic or resource-dependent economies1 , such as Nigeria, tax reform responds to the country’s economic diversification strategy, thus widening the government’s revenue base. Second, tax reform is fundamental to driving greater competitiveness for businesses through a more efficient capital allocation that results from the diminution or mitigation of fraud, corruption and transactional distortions that hitherto characterized and informed the reform in the first place. The postulation of David Bahnsen, the Chief Investment Officer of The Bahnsen Group, offers the third and final affirmative contribution of tax reform. In the December 20, 2017 issue of the Forbes Magazine, he asserts:

An economy that distributes its rewards across all income levels, to all classes of people (for those inclined to talk in such Marxian speak), which strives to drive an aspirational society, is one that absolutely has to focus on productivity. When there are incentives for expanding productivity or elimination of headwinds to productive capacity, the results will not be merely rising asset prices, but actual organic growth as capital investment drives activity.

An important resolution benefit of a tax-friendly reform is that it actively blocks extant tax loopholes which were evasion- and escape-routes for tax dodgers, thereby widening the tax net which effectively adds more individuals and small businesses in the ambit of taxation. To be sure, any government revenue enhancing programme putatively helps to bridge its funding gaps in infrastructural development and provision of public services. In the case of Nigeria, and other monolithic resource-based economies, nonoil revenue-enhancing programmes augment the country’s fiscal strength and reduce the pressure on the formal sector, lower the burden and risk of overdependence on oil revenue, and facilitate the pursuit of greater economic diversification. Tax administration reform should be an integral component of macroeconomic reform. Because monolithic economies are sandwiched by exogenous vulnerabilities on the one hand, and internal governance contradictions, on the other, proposed economic diversification must be risk-based. The overarching goal of a risk-management approach to economic diversification and development is to minimize the vulnerability of the economy to exogenous events/shocks and advance risk-adjusted real GDP growth, especially for oil resource-dependent developing economies with a narrow base of economic activity. Economic diversification is a key element of this risk-based development philosophy. In order to imbue the capacity to foster a balanced GDP growth among key sectors in the country, economic diversification must be total in all facets of the national economy. A risk-based economic diversification (development) reduces the impact of external shocks and fosters a more robust, resilient, stable and sustainable growth over the long term.

Against this background, this study examines the effect of key tax reforms on Nigeria’s economic stability, over a sixteen-year period, 2000 to 2015. Of empirical interest are Company Income Tax (CIT), Petroleum Profit Tax (PPT), and Value Added Tax (VAT). These three tax levers have particularly been found to be significant in stimulating the growth of national income (Nwaorgu et al., 2016). However, the extent to which they have been able to sustain economic stability remains an empirical issue, given their contributions to macroeconomic development. The rest of the paper is organized as follows. Section 2 summarizes Nigeria’s experience with tax reforms, as part of the relevant literature review. Section 3 presents the methodology and analytical framework of the study. Section 4 discusses the econometric results, while Section 5 concludes with recommendations and policy implications.

2. Review of Related Literature

2.1. Conceptual Issues in Tax Reform

The notion of optimal tax structure is a normative concept rather than a positive realism. Virtually all countries experience some commonality of challenges in tax administration. It is doubtful if there is any country, developed or developing, that does not desire to continuously improve their fiscal system. In most countries, the challenges largely owe their origin to perceived inefficient tax administration, usually when a new Administration comes into power, and this includes assessment, collection and creating an inclusiveness (breadth and depth) of eligible taxpayers. Developing countries typically face incremental challenges in evolving efficient tax management due to many factors which, in the main, redound to socioeconomic and demographic historicity. The aim of most tax reforms is to make revenue levels more progressive and sustainable, promote independence from natural resource revenues and foreign ‘handouts’ (in the case of developing countries), elevate the role of taxation in state-building and create a greater understanding of its impacts on growth and inequality. The foregoing consideration underscores the efficacy of tax reforms in national development and economic stability.

Current national and global economic conditions pose significant challenges for policymakers. Depending on their nature, the critical dimensions of the challenges may need to be isolated to occasion specific macroeconomic reforms. The intention of macroeconomic reforms is to leave the country in a much better and more resilient position to cope with the instability in both the national and the global economy and to continue to steer a course of economic stability. A tax administration reform is an implicit acknowledgement of the failure of extant tax system. The reform is thenceforth necessitated to remediate the defective, deficient and ineffective system. Tax reform is a conceptual fiscal policy strategy designed to enhance tax administration (Nwaorgu et al., 2016). It is a fiscal structural framework devised to strengthen responsive and accountable public governance. In general, tax reforms are concerned about creating incentives and structures that prospectively address the following concentric issues: (i) introduce focused changes to the country’s tax system; (ii) unlock tax-revenue collection in pursuit of high levels of macroeconomic growth and development; (iii) enhance tax-administration processes to enforce compliance and increase collections; (iv) improve taxpayer service and communications, and (v) guarantee transparency and accountability of the public sector by providing tools to tackle the challenges of fiscal prudence, fiscal stress, citizen accountability, and public integrity (See also: Pereira, Hoekstra, and Queijo (2013)). Put differently, a tax reform is the process of reviewing and changing the administration and collection of taxes by government with a view to boosting State revenue on the one hand, and providing greater and better socioeconomic benefits, on the other hand. These reform measures or initiatives have also been echoed by Pereira et al. (2013). Put differently, a tax reform is the process of reviewing and changing the administration and collection of taxes by government with a view to boosting State revenue on the one hand, and providing greater and better socioeconomic benefits, on the other hand.

The review of and changes in the tax administration involve a number of decision variables, including: (a) reducing the level of taxation for all taxable entities; (b) making the tax system more progressive or less progressive; (c) simplifying the tax system and making it more understandable, more friendly and more accountable; (d) plugging all known loopholes to reduce tax evasion and avoidance; and (e) allow for more efficient and fair tax collection mechanism to enhance Government’s capacity to finance public goods and services. These views have also been echoed by Rao (2014). An important goal of a fiscal reform is to create or foster an incentive environment compatible with prudent fiscal management and efficient and equitable provision and delivery of public services. The reform essentially entails changing the way taxes are collected and managed by the tax authority, the ultimate aim being to improve national income and GDP, and provide economic and social benefits to the citizenry. The notion of tax reform ab initio is an implicit admission of problems in and with the system’s fiscal management, which requires clinical diagnostic tests of the institutional arrangements for fiscal management and accountable governance as well as the interrogation of the role of taxation in macroeconomic development.

A successful tax reform involves a number of steps, precisely because it is a major component or process of fiscal consolidation. First, having recognised that there is a problem with and in the country’s fiscal system, it is important to dimensionalise the problem. This involves a clinical diagnosis of the problematics of the extant fiscal structure. This is followed by an assessment of the role of taxation as a macroeconomic tool (Islam, 2001). Until recently, many, especially resource-based, developing countries did not appear to pay much attention to the role of taxation in macroeconomic development. This inattention was due to two main factors. First, the much dependence on mineral resources for national revenues had assumed a historical proportion that successive governments’ attempts to diversify revenue base did not yield much dividend. However, with the dwindling and vagarious behaviour of prices of mineral resources at the international market juxtaposing national governments’ helplessness over the revenue profile therefrom, the locus of economic diversification has become more strident, with more and more governments paying greater attention to other sources of revenue, including taxation. The upshot is the increased focus on the role of taxation as an indispensable internal source of revenue. By unlocking the tax-revenue potential to accelerate economic growth, the fiscal management tool provides the mechanics of analysis of the issues of transparency and accountability, fiscal prudence, bureaucratic inefficiency, citizen empowerment and public integrity.

2.2. The Nigerian Economy and Key Growth Indicators

Further insights into the macroeconomic and financial conditions of Nigeria are presented in Table 1. The table shows that the GDP annual growth rate rose hugely and peaked in 2003/2004. This was due to the sudden astronomical increase in oil prices from around $48 to about $100 per barrel. Although oil prices rose above $100 per barrel in 2008/2009 following the global economic crisis, annual GDP growth was marginal, not on the scale experienced in 2003/2004. It is noteworthy that over the years, the country has witnessed a steady depreciation of exchange rate except in 2008 but reached a depth of N372.86 to $1 in 2016. Since 2017, the exchange rate has been hovering around N360 to $1. The external reserves which grew in tandem with oil price surge since 2004 reinforced the Naira appreciation and peaked in 2008 at $58.47 billion. However, while most countries have moved forward after the global economic meltdown, the Nigerian economy has continued to dawdle.

Year |

*GDP Growth (Annual %) |

GDP per capita (Current US$) |

Exchange Rate (N1=$1) |

Lending Rate (%) |

Savings Rate (%) |

External Reserves ($ Million) |

*Inflation Rate (12-month Moving Avg.) |

1999 |

0.5 |

300.6 |

92.69 |

27.2 |

5.3 |

5,309.1 |

6.6 |

2000 |

5.3 |

379.1 |

102.11 |

21.6 |

5.3 |

7,590.8 |

6.9 |

2001 |

4.4 |

351.8 |

111.94 |

21.3 |

5.5 |

10,277.5 |

18.9 |

2002 |

3.8 |

459.5 |

120.97 |

30.2 |

4.2 |

8,592.0 |

12.9 |

2003 |

10.4 |

512.7 |

129.36 |

22.9 |

4.1 |

7,641.8 |

14.0 |

2004 |

33.7 |

648.8 |

133.50 |

20.8 |

4.2 |

12,062.8 |

15.0 |

2005 |

3.4 |

807.9 |

132.15 |

19.5 |

3.8 |

24,320.8 |

17.9 |

2006 |

8.2 |

1,019.7 |

128.65 |

18.7 |

3.1 |

37,456.1 |

8.2 |

2007 |

6.8 |

1,136.8 |

125.83 |

18.4 |

3.6 |

45,394.3 |

5.4 |

2008 |

6.3 |

1,383.9 |

118.57 |

18.7 |

2.8 |

58,472.9 |

11.6 |

2009 |

6.9 |

1,097.7 |

148.90 |

22.6 |

2.7 |

44,702.4 |

11.5 |

2010 |

7.8 |

2,327.3 |

150.30 |

22.5 |

2.2 |

37,355.7 |

13.7 |

2011 |

4.9 |

2,527.9 |

153.86 |

22.4 |

1.4 |

32,580.3 |

10.8 |

2012 |

4.3 |

2,755.3 |

157.50 |

23.8 |

1.7 |

38,092.2 |

12.2 |

2013 |

5.4 |

2,997.0 |

162.45+ |

24.9 |

2.5 |

42,847.3 |

8.5 |

2014 |

6.3 |

3,221.7 |

171.45+ |

25.9 |

3.5 |

34,241.5 |

8.1 |

2015 |

2.7 |

2,655.2 |

222.79+ |

26.8 |

3.3 |

28,284.8 |

9.0 |

2016 |

(1.6) |

2,175.7 |

372.86+ |

28.5 |

4.2 |

26,990.6 |

15.7 |

2017 |

0.8 |

1,896.7 |

360.0 |

31.0 |

4.1 |

39,353.5 |

16.5 |

| Sources: *Figures in these columns were obtained from World Bank Country Statistics (2017). +Average Bureau de Change Exchange Rate (₦/US$). Except as denoted, all other figures were sourced from CBN Annual Reports, 1999-2017. |

2.3. The Limits of State Purse: The Case for Transformational Reforms

The materials in this section are drawn from Herbert (2011) early concern of the types of institutional issues that generally underpin fiscal or macroeconomic reforms. Except (Silvani & Baer, 1997) specific diagnosis of tax administration failure, sketched in the next section, there is little reason to disbelieve that the issues canvassed by the former are not conterminous with and complementary to the latter. Herbert (2011) claims that the mystery about reforms generally lies in the manner in which they are formulated, explained, and implemented. He argues that it is no more arcane than the process of budgeting or major contract awards. Reforms are not meant to be rigid, irrevocable doctrine of socioeconomic pursuit. They are not also meant to yield a bunch of aggregate statistical measures of economic growth that signify nothing about citizens’ well-being. Rather, reforms ought to be conceived, explained and couched as a pragmatic transformational response to prevailing macroeconomic challenges or realities, designed to improve citizens’ general well-being, or address specific or contentious issues such as failed tax administration.

Reforms are inevitable for three major reasons. First, the world is a state of continuous change, and no country is an island or immune to the wind of change. The antecedent intervention of governments in national economies was the consequential global devastation and dislocations of the Second World War. Since then, governments have felt an obligation to intervene, whenever the need arose, directly and positively in their national economies. The private sector was inchoate, not as organised as it is today, and international capital had not become quite as autonomous, mobile and ubiquitous as it has been since the 1970s. Besides, being the largest single employers of labour, historical corporate failures, including the recent episodes and governments’ bailouts, have shown national governments as the last frontier with the ultimate institutional capacity to alleviate the pain and groan of their societies, including those inflicted by corporate collapses. In this respect, and ironically, both Marx and Keynes, approaching the development challenge from two different inhospitable philosophies, nevertheless, were unanimous on one thing: that the state had a duty to provide the leading light to the economic regeneration of society, and provide basic needs to its citizens. Hence, for nearly 25 years after 1945, the private sector was virtually irrelevant in the public scheme of things, with governments playing the most important roles in the economic and financial management of national development. With time and the growing confidence and capacity of markets and hierarchies, the prevailing socialist model of development could not be sustained for too long, either in the socialist regimes or in the democracies.

Second, while the general and specific socio-developmental obligations of governments expanded exponentially with respect to citizens’ expectations, and with globalization progressively shrinking national economic boundaries, the resource base of national governments was correspondingly dwindling. Consequently, the idea of privatising most state-controlled agencies with commercial orientation gradually became widespread. The momentum of privatisation gathered strength and global spread with the advancement of private sector-driven markets and the changing governance policy of national governments about the intellectual realization of and conversion to the power of markets as instruments of economic change and development. Gradually, governments began to place greater focus on providing good governance (enabling environment, infrastructure and security for private sector to flourish), while the private sector was enabled to act as agents or engine of economic development through processes and instrumentalities in which it was better placed to do more efficiently (and profitably).

Third, aside the fact that the profit motive and wealth maximization is the greatest incentive to private sector activity, democracy itself almost inevitably requires governments not only to restrict their areas of direct intervention, but also demands expansion of the space available to citizens for self-assertion, both as individuals and corporate bodies. The freedom of the corporation to make money, it is argued, is as important as the freedom of the individual to vote. Thus, the true import of reforms - whether of the privatisation genre or of financial stability (more safeguards, less risk) programmes - is not that it takes full advantage of the presumed efficiency gains of private sector involvement in the provision of goods and services, or that it affords government larger revenue (in the case of privatisation, from the selling-off of the family silver). Instead, its significance lies in demonstrating that government alone can no longer do everything, efficiently or indifferently; that its resource base is finite and increasingly diminishing; and that it is ultimately impotent in the face of constantly growing and complex needs of society.

The philosophy of reform is universal; other national governments, developed and developing, tinker with various versions of it. It is an admission of the obvious conclusions drawn from the gradual shrinking of the public purse and the transactional limits of government in goods and services best furnished by the private sector; and providing necessary enabling framework (legal and structural) for the private sector to flourish, albeit under regulation and protection of consumer rights. The acknowledgement of this elementary fact underpins the reassessment of the role of government and public services.

The need to urgently seek ways to diversify the revenue portfolio of a country historically dependent on oil is anchored on some key issues. First, oil prices are determined at the international market which is beyond the circle of influence and control of many oil-producing countries. Second, international oil prices are notoriously unstable which translates to unstable domestic revenue profile. Third, when volatile revenue is paired with corruption and bad governance, vagarious policy summersault and budget implementation are consequential culprits. This scenario obfuscates fiscal sustainability and economic viability of government. Fourth, under the cash budget system on which the Nigerian economy operates, unstable revenue projections are bound to render expenditure proposals infeasible to offset. Above all, with many developed countries devising alternative energy platforms and their determination to drastically reduce dependence on oil, keeping oil as the major source of revenue is fraught with greater uncertainty, especially as such major oil producing and exporting countries (OPEC) as United Arab Emirates (UAE), Qatar, Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, Iran, and even Russia have diversified or are diversifying away from oil to alternative sources of revenue. In several of these rich OPEC members and Russia, tourism accounts for more than 10% of their GDP. Notwithstanding a substantial net export of oil, a forward-looking economy must recognize the limiting effect of oil revenue and adopt strategies towards a more diversified revenue base and economy. Historically, the Nigerian revenue profile has been fundamentally pegged to petroleum taxes with direct and indirect taxes being addressed with less zeal and intensity. Yet, there is a structural problem in Nigeria’s tax system. While direct and indirect tax structures have enormous room for expansion, their impact is limited because of organizational inefficiency in building incentives and harnessing the opportunities in the dominant informal sector of the economy. Another compelling reason for tax reform is the spiralling fiscal deficit which is both a threat to macroeconomic stability and economic growth (Dockery, Ezeabasili, & Herbert, 2012; Okafor, 2012). Enlarging the revenue base will, ipso facto, trim fiscal deficit expansion risk.

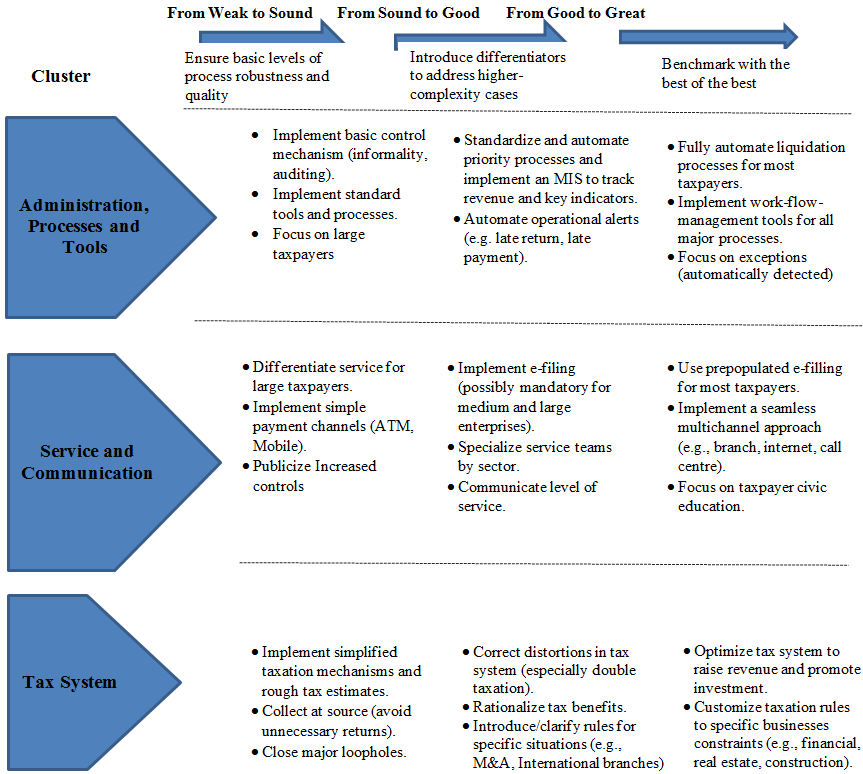

Table-2. A Transformational Journey of a Tax Ecosystem.

2.3.1. A Transformational Journey of a Tax Ecosystem

Studies have shown that tax reforms have strong effects on macroeconomic growth (See, (Engen & Skinner, 1996; Nwaorgu et al., 2016)). It is hypothesized that the design and composition of the tax system has as much a determinative effect on economic growth as the absolute level of taxation (Engen & Skinner, 1996). The authors further advance that countries with better mobilizational capacity and more efficient administration and enforcement mechanisms are likely to experience faster growth rates (and economic stability) than countries with lower capacity in mobilization, tax assessment and inefficient collection structures. Thus, an effective tax policy is one that is not only progressive but also ensures that every taxable citizen voluntarily pays their tax as and when due. However, getting this policy right is both a desideratum and a challenge in Nigeria and the SSA in general. Table 2 displays a stylized tax ecosystem for a holistic and sustainable tax reform. It is a trilateral cluster project phased into (i) administration, processes and tools; (ii) service and communication; and (iii) tax system.

The trajectory of the tax ecosystem is also progressively structured to transit from: (a) weak to sound ecosystem, designed to ensure basic levels of robust and quality process; (b) sound to good ecosystem, based on key differentiators of complex cases; and (c) good to great tax ecosystem by benchmarking against international best practices. Tax matters can be as simple as they can be complex, especially with large multinational companies with multiple tax ecosystems and arrangements. The strategies of the multinationals are geared towards minimising their tax liabilities while striving at the same to maintain good corporate citizenship. The fiscal strategies of any focused government are to build a robust, progressive and vibrant tax ecosystem for a better forward-looking tax administration. As most large corporate organisations have in-house tax expertise or engage the services of external tax consultants, a good tax ecosystem must attract, nurture and retain tax talent. Ultimately, a tax ecosystem should optimise revenue generation and promote investment thereby. It may also warrant customising taxation rules to specific business segments or sectors, such as construction, financial, real estate, and so on.

2.4. Theoretical Framework

Dynamic governments are continually appraising and reassessing strategies of improving their public finances. As taxation is a leading source of public revenue, tax administration is ostensibly an important strategic tool in the hands of government since it has the power to impose taxation also lies in the hands of government. Nwaorgu et al. (2016) surmised the essence of tax reforms in the following way.

Tax reforms can be either progressive or retrogressive and dysfunctional. A progressive tax system is one that (a) is growth-oriented, (b) aggressively seeks to minimize the distortions of market signals by the tax system, and (c) promotes convergent expectations, serving in this way to attenuate uncertainties and obstacles to investment, innovation, entrepreneurship and other drivers of economic growth.

A tax system should be anchored on social and political objectives or considerations. In essence, a tax system should not be based on the specific needs of citizens or individual members of the society, but on the overall good of the society. This is the basis of the socio-political theory of taxation which underlies the progressive tax system as a means to reduce income inequalities. Because the society is more than the sum total of its individual members, its existence as a collective entity needs to be preserved and protected beyond the individual members’ idiosyncrasies. Accordingly, the purpose and scope of taxation should be wide and effective to accommodate, but not limited to, the following: alleviating unemployment; checkmating monopolistic and restrictive trade practices such as hoarding and artificial barriers, cyclical fluctuations, and regional disparities; and creating a balanced growth across different trade, business or service zones.

2.5. Conceptual Issues in Economic Stability

No single statistical measure is sufficiently analytic to summarise the complexity of the modern national economy. However, the knowledge of the dimensionality of a particular macroeconomic variable, GDP, has been historically significant. Most economic research and economic policy analyses use GDP as a powerful comprehensive summary of economic activity. In other words, the empirical foundations of economic stability are set in changes in the GDP over time as a unit of analysis. Economic stability refers to economic condition of a country that is devoid of wide fluctuations in key indices of economic performance, such as gross domestic product, unemployment or inflation. This understanding has been facilitated by research attention to the dimensionalities and measures necessary to explain changes in GPD over time and their implications for economic growth, development, employment and inflation. Stable economies manifest modest growth in GDP and job creation while holding inflation to a minimum. Economic stability implies greater economic prosperity, powered by productivity growth alongside higher levels of employment. The productivity performance of the Nigerian economy has historically been weak and this has created a substantial productivity gap, castrated economic development, and weakened revenue generation. In this economic quagmire, it is more important than ever that reforms are introduced to close both the productivity and revenue gaps. A friendly tax reform is designed to attract more tax payers into the net, incentivize the informal sector to voluntarily enlist into the formal sector, create employment opportunity, and build a stronger economy and fairer society.

2.5.1. Objectives of Economic Stability

The central objective of economic stability is to maximise the rate of sustainable growth and maintain rising prosperity by creating and widening the gamut of economic and employment opportunity. The strategic elements of economic stability are: (i) maintaining macroeconomic stability, (ii) sustaining fiscal stability, (iii) safeguarding financial stability, (iv) addressing the productivity challenge, (v) increasing employment opportunity, (vi) delivering quality public services, and (vii) protecting the environment. For Nigeria, in particular, the ingredients of economic stability reside in macroeconomic policy of government, whose goals are fiscal policy stability and price or monetary stability. Fiscal stability is concerned with maintaining a balance between government tax revenue and government expenditure such that there is no mismatch or gap between government borrowing and debt service costs. Where government borrowing exceeds a limit that makes future interest payments prohibitively burdensome on government treasury, not only is fiscal instability immediately invoked, but also macroeconomic goals are thrown into serious jeopardy. Over the years, Nigeria has been under the weight of fiscal instability, with government spending outpacing revenue year in, year out. The perennial fiscal deficits are due to the rising gap between government tax revenue and expenditure, and excessive or imprudent government borrowings which have generated growing and unsustainable debt service costs. Financial system stability is critical in sustaining seamless financial intermediation, absorption of system shocks, minimisation of systematic risks other risks such as nonperforming loans that can potentially trigger financial crisis and threaten macroeconomic stability.

On the flipside of the economic stability coin is monetary stability, referring to a regime of stable price levels or a low level of inflation. Price stability is a significant objective of monetary policy whose target is to ensure that inflation is contained or that it is not high enough to interfere with the efficient operation of the economy or destabilise fiscal (and trade) policies. Inflation has a pervasive painful effect on the economy such that if allowed to spiral, or if expectations of high inflation are held, it becomes an uphill task to deflate. A prudent strategy of economic stability is aimed at creating a balance between the two policy levers, that is, aligning fiscal and monetary policies so as to achieve some equilibrium. Macroeconomic policy objective is to stabilize the economy via a steady growth of GDP and productivity while keeping inflation in check.

2.6. Empirical Framework

The 2000s decade witnessed an enormous upsurge in the number of economic activities in Nigeria, including institutional reforms and changes to herald the young democratic governance after several years of military interregnum. The following significant tax administration reforms were initiated as part of the macroeconomic transformation: Company Income Tax Act, (CITA) 2004; Personal Income Tax Act (PITA), 2004; Value Added Tax Act (VAT), 2004; Petroleum Profit Tax Act (PPTA), 2004; Capital Gain Tax Act (CGTA), 2004; Education Tax Act (ETA), 2004; the Federal Inland Revenue Service Establishment Act (FIRS), 2007; Personal Income Tax (Consolidated) Act (PITA), 2011; Transfer Pricing Tax Act (TPTA), 2012; and Income Tax Reform Act (ITA, 2014.

A number of studies have examined different dimensions of these tax reforms and their associated impact on economic development. These include studies by Adereti, Adesina, and Sanni (2011) on the effect of VAT on economic growth of Nigeria; Owolabi and Okwu (2011) and Enahoro and Jayeola (2012) on the contribution of VAT to the economic development of Lagos State, and the economic consequences of tax administration on revenue generation of Lagos State, respectively; Abiola and Asiweh (2012) on the relationship between CIT and Nigeria’s economic development; Okafor (2012) on the impact of tax reforms (proxied by PPT, VAT, Customs and excise duties (CED) and CIT) on Nigeria’s economic growth for the period 1981 to 2007; Ogbonna and Ebimobowei (2012) on the impact of tax reforms on Nigeria’s economic growth from 1994 to 2009; Umeora (2013); Abata (2014) and Ofishie (2015) on the impact of VAT on economic growth of Nigeria over different time periods; Aminu and Eluwa (2014) on the impact of tax reforms on government revenue generation in Nigeria;Oriakhi and Ahuru (2014) on the impact of tax reforms on tax revenue generation in Nigeria between 1981-2011; Jones and Ekwueme (2016) on the impact of tax reforms on Nigeria’s economic growth from 1985-2011; Nwaorgu et al. (2016) on the impact of changes in Nigeria’s tax structure (depicted by tax reforms) on national income between 1971 and 2014; and Herbert, Nwaorgu, and Nwaiwu (2017) on the relationship between oil revenue generation and economic growth in Nigeria during the 45-year period, 1971 to 2015.

Two things are noteworthy from both empirical and anecdotal observations of Nigeria’s internal resource management, of which tax administration is a prime constituent. First, the average conclusion of these studies is that a positive and significant relationship exists between tax revenue and economic growth (measured by GDP growth) or that tax reforms have significant impact on the economic growth of Nigeria. Second and important too, Nigeria’s tax structure, as with its macroeconomic management in general, has been largely perceived and described as incompetent, inefficient and ineffective. Such adjectival phrases as ‘improper tax administration’, ‘failure in or improper tax enforcement’, ‘underassessment’, ‘inefficient tax collections’, ‘tax avoidance and evasion’, and similar constitutive semantics have all been used to characterize Nigeria’s tax administration system. The reality is that these expressions are all euphemisms for corruption in the tax administration. These have variously been used in similar contexts to qualify the egregious distortions in and failure of the Nigeria’s tax system (See, for example, (Adegbie & Fakile, 2011; Aguolu, 2010; Oluba, 2008; Ordu & Anele, 2015)). These studies affirm anecdotal comments that the above semantics tend to colour and obscure the harmful impact of fraud and corruption in revenue mobilizational capacity and governance of internal resources of Nigeria, including tax assessment, revenue collection and accountability, and on the stability of the economy. In consequence, many developing countries, qua SSA, suffer from debilitating and dysfunctional governance systems, encompassing inappropriate allocation of state resources, inefficient revenue systems, and weak delivery of vital public services (Léautier, 2005). The pairing of these with rapacious corruption, bad leadership and weak institutions suffocates economic development and stability.3. Methodology

The starting point for understanding the role and modelling apparatus of taxation is aptly captured by Nwaorgu et al. (2016) in their assertion that: “theoretical foundations about taxation must be anchored on the backdrop of two major considerations. First is the universal consensus that all tiers of government need lots of revenue to finance public-sector expenditures and these must be raised from a variety of sources. The funds are necessary to anchor sustainable development goals – primarily, economic development, social development and environmental protection. Second, taxation details are guided by two principles: ability to pay, and expected benefit. Any tax reforms must therefore be anchored on these two precepts.”

3.1. Model Specification

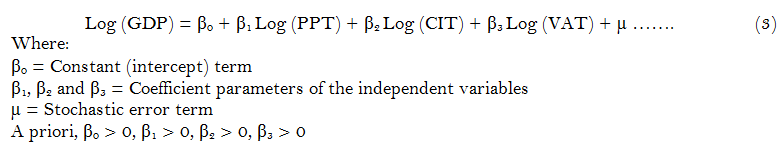

The dependent variable is GDP while the independent variables are PPT, CIT and VAT. Thus, the model is expressed as:

GDP = ʃ(PPT, CIT, VAT) (1)

Where:

GDP = Gross domestic product (proxy for economic stability)

PPT = Petroleum profit tax (proxy for petroleum profit tax reform)

CIT = Company income tax (proxy for company income tax reform)

VAT = Value-added tax (proxy for value-added tax reform)

Transforming equation (1) into econometric linear form yields equation 2 as follows:

![]()

The logarithmic transformation2 of equation (2) is designed to bring the variables to the same base, hence the model becomes:

4. Data Analysis and Discussion

4.1. Data Analysis

The time series data were obtained from the Federal Inland Revenue Services (FIRS) publications and Central Bank of Nigeria (CBN) Statistical Bulletin. Various tax reforms were factored from revenues generated through the different types of taxation, while GDP was adopted as a proxy for economic stability (See also: Nwaorgu et al. (2016)). In the main, the revenue increases were a consequence of tax administration reforms in (a) Petroleum profit tax (PPT), (b) company income tax (CIT), and (c) Value-Added Tax (VAT).

4.2. Discussion

The Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) result, presented in Table 3, depicts positive and significant relationship between PPT, CIT, respectively and economic stability. One significant observation about the results is the conformity to the economic theoretical expectation that as more revenues are generated from reforms in petroleum profit tax, company income tax, and value added tax, the federally generated revenues substantially increase which, in turn, enhance economic growth and stability.

| Dependent Variable: LOG(GDP) | ||||

| Sample: 2000 2015 | ||||

| Included observations: 16 | ||||

| Variable | Coefficient |

Std. Error |

t-Statistic |

Probability |

| C | 3.650195 |

0.074065 |

49.28384 |

0.0000 |

| LOG(PPT) | 0.058280 |

0.024812 |

2.348891 |

0.0368 |

| LOG(CIT) | 0.248310 |

0.029188 |

8.507327 |

0.0000 |

| LOG(VAT) | 0.074932 |

0.041854 |

1.790326 |

0.0986 |

| R-squared | 0.988160 |

Mean dependent var | 4.637187 |

|

| Adjusted R-squared | 0.985201 |

S.D. dependent var | 0.150526 |

|

| S.E. of regression | 0.018312 |

Akaike info criterion | -4.950213 |

|

| Sum squared resid | 0.004024 |

Schwarz criterion | -4.757066 |

|

| Log likelihood | 43.60171 |

Hannan-Quinn criter. | -4.940323 |

|

| F-statistic | 333.8518 |

Durbin-Watson stat | 1.293795 |

|

| Prob(F-statistic) | 0.000000 |

|||

However, the positive relationship between VAT and economic stability is not significant. We now discuss the specific content and context of each individual relationship in relation to economic stability.

Table 3 is a derivative of Appendix A and represents the logarithmic transformation of the econometric linear model specified in equation 1. The result suggests that a one percent increase in PPT leads to 0.06 percent increase in Nigeria’s GDP (as a proxy for economic stability). The probability value of the PPT (0.0368) is less than the test significance level of α < 0.05), implying the significant effect petroleum profit tax reforms have on economic stability. This outcome corroborates (Ogbonna & Ebimobowei, 2012) result of a positive and significant impact of PPT on Nigeria’s GDP. It is a historical fact that Nigeria relies heavily on revenues from the oil industry. Mapping and implementing efficient and effective tax policies and reforms would increase revenue from petroleum products.

Next, the significant contribution of company income tax (CIT) to Nigeria’s economic stability justifies its reform. Table 3 also shows that a 1 percent increase in company income tax yields a quarter of a percent increase in GDP (a proxy for economic stability) in Nigeria. The probability value of 0.0000 conclusively confirms the significant impact of company income tax reforms on economic stability in Nigeria. This finding is consistent with the evidence of Nwaezeaku (2005). The positive effect of company income tax on GDP derives from its role in the dynamic business environment, aided by technological interface. Since the current democratic dispensation, the FIRS has adopted high-tech applications in the assessment and collection of accrued taxes from companies and thus reduce the incidence of tax avoidance or evasion. This has contributed in boosting the nation’s economic stability.

Finally, the table shows that a one percent increase in VAT leads to 0.07 percent increase in economic stability. However, the VAT probability value of 0.0986 is greater than the test significance level of 0.05, implying that VAT reform offers little or no significant impact on economic stability. The positive relationship between VAT and economic stability is not surprising since most sales are subject to VAT. VATable goods are collected at the purchase points, making it difficult to evade, and the rich tend to spend more than the poor on such goods. Thus, as VAT revenue increases, economic growth and stability in Nigeria may increase. However, the negligible contribution of VAT to economic growth and stability may be due to three major factors, namely: (i) the low percentage rate of VAT, (ii) its narrow base, (iii) VATable goods and services are generally small, and (iv) high remittance failure by most shopkeepers and purveyors of VATable goods and services, for reasons not far-fetched from collusive corruption. All these factors combine with corrupt and inefficient VAT administration to undermine its influence on economic growth and stability. Furthermore, Nigeria is one of two countries with the lowest VAT rate of 5 percent, the other being Mauritius. The need to review the VAT regime from the current rate of 5 percent to a minimum of 7.5 percent has been mooted by various scholars (See: (Herbert, 2015a; Kolade et al., 2015)). Ekeocha (2010) had suggested same, but to 15 percent. There is a growing consensus that the 5 percent is insufficiently significant to induce positive economic changes.

The coefficient of determination (adjusted R-squared) shows that 99 percent of the variations in economic stability of Nigeria are caused by changes in petroleum profit tax, company income tax and value-added tax. The remaining one percent is due to other factors not included in the model. This result represents a very good fit. The probability F-statistic (0.000000) is a clear indication of the reliability, significance and fitness of the model for sound policy making. The Durbin-Watson Test statistic for the null hypothesis of zero autocorrelation in the residuals is 1.29. We therefore reject H0 and conclude that the errors are positively autocorrelated. Also, the D-W statistic (1.29) is greater than the R2 (0.99), which clearly indicates that the regression result is not spurious, with 99 percent of the dependent variable (economic stability) explained by the independent variables.

5. Conclusion and Policy Implication

This paper recognises the inadequacies of extant tax administration as the raison d'être for tax reforms. It identifies the key elements of Nigeria’s taxation that are levers of the country’s fiscal structure, the efficient management of which would improve the country’s revenue profile. Research, including the present one, has shown that effective and efficient tax administration is necessary for a country’s fiscal management and macroeconomic development. Tax reforms represent a fundamental strategy in the governance of a country’s fiscal structure. That tax administration in many countries does not function optimally and/or distorts the intention of tax laws (Pellechio & Tanzi, 1995) is a fundamental acknowledgement of organizational failure. The intention is to make taxation an effective and efficient tool in the allocation of resources, distribution of income, and macroeconomic growth and stability. Tax reforms are necessitated under the following three conditions: (a) there is an exigency to modernize tax administration as part of a broad fiscal reform strategy or in response to observed deficiency, inefficiency and ineffectiveness in the tax system; (b) a response to the demands of a growing economy, in which expansion of the tax net is needed to integrate uncaptured tax payers, such as the growing number of informal sector players; and (c) the imperatives of ICT and software applications as well as changes in macroeconomic policies dictate the need for or compel fiscal reforms, for example, to complement macroeconomic, trade and investment policies.

The study explored the link between tax reforms and economic stability in Nigeria. We specifically used tax revenues induced by reforms in petroleum profit tax, company income tax, and value-added tax, as independent variables on the one hand, and GDP (dependent variable) as a proxy for economic stability, on the other hand. From the empirical analysis, we found that reforms in both petroleum profit tax and company income tax have positive and significant effect on economic stability. But, the same conclusion could not be reached with value-added tax reforms. Although VAT reforms have positive relationship with economic stability, the effect is, however, insignificant. This negligible contribution may be attributed to a combination of factors, including low percentage rate of the VAT and failure to remit. It is instructive from the findings that while tax reforms in general have a significant impact on economic growth and stability, the reforms narrative merits a careful evaluation of their content and context. The distortionary effect of corruption on economic growth is rooted in and routed from several trajectories. The interest here is on the egregious diversion of public treasury, in particular tax revenues, which would otherwise be committed to budgetary use. The corrupt diminution of public capital increases linearly with the intensity of corruption, decreases the growth-maximizing influence and intensity of tax revenues, hinders investment, and impedes economic growth and stability. This view is also shared by Dissou and Yakautsava (2012).

A critical factor at the interface of Nigeria’s tax administration reforms is the role of taxation on the development of public tertiary education. The Tertiary Education Trust Fund (TETFund) Act, 2011 created TETFund as an intervention agency for the development of public tertiary education in Nigeria. The Act imposes a 2% education tax on the assessable profits of all registered companies in Nigeria. The mandate of TETFund is to administer (that is, manage, disburse and monitor) the education tax to public tertiary institutions in Nigeria. The Act also empowers the Federal Inland Revenue Service (FIRS) to assess, collect education tax and transfer same to the Fund. So, as tax reforms enhance the revenue profile of Government, so will the Fund’s revenue accretion potentially lead to more even development of public tertiary educational institutions, which will, ceteris paribus, help to stabilize this critical sector of the economy.

We conclude with the following policy suggestions. First, although increasing the VAT rate may sound unpopular in a country ravaged by poverty and hardship, however, a moderate increase (to say, 7.5%), as has been canvassed by several commentators, would boost government’s revenue profile. Similarly, expanding the base of VAT would be a progressive attempt at revenue expansion as it will potentially bring the informal sector into the tax net, thereby enhancing the nation’s economic stability. Second, the importance of company income taxes suggests the need to harmonise policies that prospectively address the vexatious incidence of multiple taxation. Removal of multiple taxation will considerably reduce the incidence of company income tax evasion and bring stability thereby. Third, the significance of petroleum profit tax as a major contributor to Nigeria’s economic growth and stability should compel expeditious policy action on the long-awaited petroleum industry reform bill. The reform is expected to streamline and strengthen the industry for greater productivity and enhanced revenue generation. Finally, policy measures that seek to achieve greater economic diversification (purposely of export-oriented sectors), mitigate the impact of external shocks from the oil market, and foster more robust, resilient economic growth over the long term, are affirmative actions in the drive to bolster the country’s economic stability. Above all, the governance architecture of Nigeria’s tax ecosystem must be improved to validate the certainty and administrative integrity and transparency of taxation. Macroeconomic reforms generally, more so in SSA countries, must develop targeted and industry-focused fiscal initiatives and programmes that will stimulate productivity, competitiveness, efficiency, employment growth and drive tax revenues, all of which will help to stabilize the economy.References

Abata, M. A. (2014). The impact of tax revenue on Nigerian economy: A case of federal board of Inland revenue. Journal of Policy and Development Studies, 9(1), 109-121.

Abiola, J., & Asiweh, M. (2012). Impact of tax administration on government revenue in a developing economy-A case study of Nigeria. International Journal of Business and Social Science, 3(8), 99-113.

Adegbie, F. F., & Fakile, A. S. (2011). Company income tax and Nigeria economic development. European Journal of Social Sciences, 22(2), 309-319.

Adereti, S., Adesina, J., & Sanni, M. (2011). Value added tax and economic growth of Nigeria. European Journal of Humanities and Social Sciences, 10(1), 456-471.

Aguolu, O. (2010). Tax reform in Nigeria: Unrealized expectations. Bulletin for International Taxation 64(1), 61-67.

Aminu, A. A., & Eluwa, D. I. (2014). The impact of tax reforms on government revenue generation in Nigeria. Journal of Economic and Social Development, 1(1), 1-10.

Bird, R. M. (2015). Improving tax administration in developing countries. Journal of Tax Administration, 1(1), 23-44.

Dissou, Y., & Yakautsava, T. (2012). Corruption, growth, and taxation. Theoretical Economics Letters, 2(1), 62-66.

Dockery, E., Ezeabasili, V. N., & Herbert, W. E. (2012). On the relationship between fiscal deficits and inflation: Econometric evidence for Nigeria. Economics and Finance Review, 2(7), 17 – 30.

Ekeocha, P. C. (2010). Modelling the potential economic effects of VAT reform: Simulation analysis using computable general equilibrium analysis.

Enahoro, J. A., & Jayeola, O. L. (2012). Tax administration and revenue generation of Lagos State government, Nigeria. Research Journal of Finance and Accounting, 3(5), 133-139.

Engen, E., & Skinner, J. (1996). Taxation and economic growth. National Tax Journal, 49(4), 617-642.

Herbert, W. E. (2011). State capacity and the politics of economic reform in Nigeria: Some critical issues. Journal of Business and Financial Studies, 2(2), 35-58.

Herbert, W. E. (2015a). Reviving the economy to catalyse national growth and development, confidential memorandum to the president. Federal Republic of Nigeria, May.

Herbert, W. E., Nwaorgu, I. A., & Nwaiwu, J. (2017). The tenuous relationship between oil revenue and Nigeria’s economic growth. European Journal of Accounting Auditing and Finance Research, 5(6), 51-76.

Hogue, M., Hassel, V. H., Olsson, G., Sabbe, F., & Ott, L. (2000). Comparative approaches to central and Eastern European countries tax administration reform. Budapest: Local Government and Public Service Reform Initiative, Open society Institute.

International Monetary Fund (IMF). (2018). Regional economic outlook, Sub-Saharan Africa, 2018. IMF: Washington, D.C.

Islam, A. (2001). Issues in tax reforms. Asia-Pacific Development Journal, 8(1), 1-12.

Jones, E., & Ekwueme, D. C. (2016). Assessment of the impact of tax reforms on economic growth in Nigeria. Journal of Accounting and Financial Management, 2(2), 15-28.

Kolade, C., Kalu, I. K., Herbert, W. E., Rewane, B., Salami, D., Osadolor, V., . . . Okebukola, P. A. (2015). Revitalising the national economy to catalyse growth and development, Ch. 38. In: Obasanjo, O., Mabogunje, A. L. & Okebukola, P. A (pp. 611-645). Towards a New Dawn in Nigeria Post 2015. Abeokuta, Nigeria: Centre for Human Security, Olusegun Obasanjo Presidential Library.

Léautier, F. A. (2005). Foreword to Shah, A. (Ed.) Fiscal management: Public sector governance and accountability series. Washington DC: The IBRD/World Bank.

Nwaezeaku, N. C. (2005). Taxation in Nigeria: Principles and practice. Owerri: Springfield Publishers.

Nwaorgu, I. A., Herbert, W. E., & Onyilo, F. (2016). A longitudinal assessment of tax reforms and national income in Nigeria: 1971-2014. International Journal of Economics and Finance, 8(8), 43-52.

OECD. (2009). Tax administration in OECD and selected non-OECD countries: Comparative information series, 2008. Retrieved from http://www.oecd.org/ dataoecd /57/23/ 420 12 90.pdf.

Ofishie, O. W. (2015). The impact of value added tax on economic growth in Nigeria (1994-2012). Research Journal of Finance and Accounting, 6(23), 34-46.

Ogbonna, G. N., & Ebimobowei, A. (2012). Impact of tax reforms and economic growth of Nigeria: A time series analysis. Current Research Journal of Social Sciences, 4(1), 62-68.

Okafor, R. G. (2012). Tax revenue generation and Nigerian economic development. European Journal of Business and Management, 4(19), 1905-1922.

Oluba, M. N. (2008). Justifying resistance to tax payment in Nigeria. Economic Reflections, B(3). April, 2008.

Ordu, P. A., & Anele, C. A. (2015). A performance analysis of Nigerian tax objectives actualization: Evidence of 2000-2012. International Journal of Management Science & Business Administration, 1(6), 88-100.

Oriakhi, D. E., & Ahuru, R. R. (2014). The impact of tax reforms on federal revenue generation in Nigeria. Journal of Policy and Development Studies, 9(1), 92-108.

Owolabi, S., & Okwu, T. (2011). Empirical evaluation of contribution of value added tax to development of Lagos State economy. Middle Eastern Finance and Economics, 1(9), 24 –34.

Pellechio, A. J., & Tanzi, V. (1995). The reform of tax administration. IMF Working Paper Series No. 95/22: 1-26.

Pereira, F. G., Hoekstra, W., & Queijo, J. (2013). Unlocking tax-revenue collection in rapidly growing markets, public sector. Amsterdam: McKinsey & Company.

Rao, S. (2014). Tax reform: Topic guide. Birmingham, UK. GSDRC: University of Birmingham.

Rossiter, C. (1961). The federalist papers. New York: New American Library.

Silvani, C., & Baer, K. (1997). Designing a tax administration reform strategy: Experiences and guidelines. A Working Paper of the International Monetary Fund, IMF WP/97/30: 1-36.

Taliercio, R. R. (2004). Administrative reform as credible commitment: The impact of autonomy on revenue authority performance in Latin America. World Development, 32(2), 213-232.

Umeora, C. E. (2013). The effects of value added tax (VAT) on the economic growth of Nigeria. Journal of Economics and Sustainable Development, 4(6), 190-201.

World Bank Country Statistics. (2017). World development indicators (WDI).

Footnotes:

2.The log transformation is, arguably, the most popular among the different types of transformation. It is utilised (a) to transform skewed data to approximately conform to normality, that is, when the distribution of the continuous data is non-normal and the need to make the data as ‘normal’ as possible; (b) to increase the validity of the associated statistical analyses; to reduce the variability of data, especially for data sets with outliers. Log-transformed data permits the application of several statistical methods, including linear regression, to model the resulting transformed data.