Social Protection and Children Vunerability in Ghana: An Evidence from the Wa and Jirapa Municipalities

Eric Dalinpuo1*

Theophile Bindeoue Nasse2

1University for Development Studies, Wa Campus, Ghana. |

AbstractThough Ghana has made impressive strides in terms of economic growth, poverty reduction and democratic governance, there remains a substantial percentage of the population that still lives in poverty and are vulnerable to a range of economic, social, lifecycle and environmental shocks and risks. Therefore, Ghana rolled out a number of social protection interventions under the National Social Protection Strategy (NSPS) to mitigate the impact of extreme poor and vulnerabilities in society, especially among vulnerable children. The main objective of the study was to examine social protection and children vulnerability in Ghana by employing both qualitative and quantitative methods in achieving the objectives of the study in the Jirapa and Wa Municipalities of the Upper West Region of Ghana. Secondary literature and primary data were combined. The methods for data collection were questionnaire and interviews to generate information from government departments and institutions providing social protectionist services. Results suggest that there is increasing levels of vulnerability and orphanhood in children in the region. However, SP has some improvement in beneficiaries household food consumption, income levels, saving levels, access to healthcare, and school attendance. However, there are institutional challenges that affect the implementation of the SP programme. The study concludes that SP programme contributed to poverty reduction as it enhanced beneficiaries’ living conditions. It is therefore recommended that the Department of Social Welfare (DSW) be strengthened to properly target the real vulnerable children and households in their registration. |

Licensed: |

|

Keywords: |

|

|

|

| (* Corresponding Author) |

Funding: This study received no specific financial support. |

Competing Interests:The authors declare that they have no competing interests. |

Acknowledgement:The authors would like to thank the University for Development Studies, more especially Professor Agnes A. Apusigah for her contribution to this research. The authors would also like to thank the International Journal of Social Sciences Perspectives editorial board and all persons who in one way or the other contributed to this research. |

1. Introduction

The subject of social protection throughout the world has gained prominence in the international policy-making and developmental circles over the years. However, the issue of formal state social protection is itself minimal in most developing world, especially Africa. Hence, debates on state social protection have often been fueled mainly by discussions within developing countries where poverty and vulnerability are endemic compared to those of developed countries as observed by Greenblott (2007).

According to Handa and Park (2012) the last two decades have witnessed a number of countries in the developing world, particularly those in sub-Saharan Africa, demonstrating a keen interest in designing and implementing social protection programmes as a strategy for fighting chronic poverty and deprivation. In this regards, the Inter-Agency Task Team (2008) has indicated that there is no single “right” model of social protection and as such, each society must determine how best to ensure the social protection of its members and these choices will reflect a society’s social and cultural values, its history, the structure and capacity of local institutions and overall level of economic development. Today, all over the world, social protection is advocated in the context of children vulnerability and basic human rights, thus all human beings have the basic right for social protection in the first place and so vulnerable children.

To buttress the above assertion, Greenblot (2008) who presented a working paper for the IATT on children and vulnerability has this to say: “Social protection is a basic entitlement; with social security recognized as human right and social protection mechanisms understood as enablers for realizing the broader range of basic human rights” (IATT, 2008).

According to the IATT working group, African countries in particular have articulated a desire for social protection that is needs-based and context specific such that programmes are designed in universalism in order to reach out to the highest proportions of the vulnerable group in society. Jones, Ahadzie, and Doh (2009) writing for UNICEF, have indicated that social protection is widely seen as an important component of poverty reduction strategies and efforts to reduce vulnerability to economic, social, natural and other shocks and stresses. It is particularly important for children, in view of their heightened vulnerability relative to adults, and the role that social protection can play in ensuring adequate nutrition, utilisation of basic services (i.e., education, health, water and sanitation) and access to social services by the poorest. Social Protection is understood not only as being protective (by, for example, protecting a household’s level of income and/or consumption), but also as providing a means of preventing households from resorting to negative coping strategies that are harmful to children (such as pulling them out of school), as well as a way of promoting household productivity, increasing household income and supporting children’s development (through investments in their schooling and health), which can help break the cycle of poverty and contribute to growth. The question is: How can social protection help to get rid of children vunerability in Ghana?

This study was therefore guided and informed by the growing concern over the government‘s neglect of social protection and effective access to social rights and especially of vulnerable children in Northwestern Ghana. Hence, the study was guided by two objectives. The first objective is to examine social protection and children vulnerability in Ghana. The second objective is to determine the impacts of existing social protection policies and strategies in responding to the support needs of vulnerable children. The next section shows the review of the literature.

2. Review of Related Literature

2.1. The Concept of Vulnerability

Smart (2003) revealed that vulnerability is a complex concept to define. Due to its complexity in definition, according to Smart, local/communities have various definitions of vulnerability, which often include disabled or destitute children; in policy and support provision definitions, which list categories of children; and in working definitions, which are used in various documents. The concept of vulnerability is not only restricted to individuals, such as children, but is often used to refer to households as well.

PEPFAR (2006) looked at vulnerability as an embodiment of any or all of the following factors that result from HIV/AIDS:

- Is HIV-positive.

- Lives without adequate adult support (e.g., in a household with chronically ill parents, a household that has experienced a recent death from chronic illness, a household headed by a grandparent, and/or a household headed by a child).

- Lives outside of family care (e.g., in residential care or on the streets).

- Is marginalized, stigmatized, or discriminated against.

In conceptual terms, a vulnerable child is one who is living in circumstances with high risks and whose prospects for continued growth and development are seriously impaired. But UNAIDS refer to vulnerable children as children whose survival, well-being, or development is threatened by HIV/AIDS UNAIDS. (2004). It is important to recognize that there is no commonly agreed definition for vulnerability as indicated early. A common purpose across most definitions is to protect society’s most vulnerable members through the provision of certain goods and services, including health, education and social services that provide financial, material, social or psychological support to people who are otherwise unable to obtain it through their own efforts and that is what this study seeks to establish.

In Ghana, the National Plan of Action for OVC indicated that the concept of vulnerability is even more complex. The most vulnerable children in need of special measures for care and protection are those who, for whatever reason, face a high risk of neglect and discrimination, emotional, physical or sexual abuse and violence and/or economic and sexual exploitation. Children’s vulnerability will vary during childhood according to their own and the family’s circumstances – economic status, ethnicity, size, age and gender, health and family situation (See NPA, 2010-2012).

Children vulnerability is also slightly depicted by Nasse (2019) in a context where a non-moderated alcohol consumption not only leads to some household conflictual situations, but also to the reduction of the household income and therefore, these situations make children and the whole family vunerable.2.2. Understanding the Concept of Social Protection

Existing literature shows that there are many and different understandings of the term, Social Protection. Although social protection has recently become mainstreamed in development discourse, it remains a term that is unfamiliar to many and carries a range of definitions, both in the development studies literature and among policymakers responsible for implementing social protection programmes. Sabates-Wheeler and Pelham (2006) describe Social protection as all public and private initiatives that provide income or consumption transfers to the poor, protect the vulnerable against livelihood risks, and enhance the social status and rights of the marginalized; with the objective of reducing the economic and social vulnerability of poor, vulnerable and marginalized groups. This definition seemed to be more accepted in the international front as comprising the four pillars of protective, preventive, promotive, and transformative social protection. This definition was also adopted by UNICEF and IDS.

Research works of other organisations revealed different understanding of Social Protection. The ILO asserts that Social Protection is having security in the face of vulnerabilities and contingencies, it is having access to health care and it is about working in safety. According to Abebrese (2011) is an important strategy to protect people from chronic poverty and from risks and shocks. For the World Food Programme (WFP) cited by Greenblott (2007) social protection is an integrated system of institutionalized national measures, which may include contributory pensions, insurance schemes and safety nets. Safety nets are further defined as the social protection component targeted at the most vulnerable sections of a population.

Writing for the Overseas Development Institute (ODI), Greenblott (2007) defined social protection as range of processes, policies and interventions to enable people to reduce, mitigate, cope with and recover from risk in order that they become less insecure and can participate in economic growth. Governments and donor agencies increasingly recognize the need to provide protection for the poor against income fluctuations or livelihood shocks. In this context, ‘social protection’ is an umbrella term covering a range of interventions, from formal social security systems to ad hoc emergency interventions to project food aid (Ibid).

Social protection is thus an important strategy to protect people from chronic poverty and from risks and shocks. There are other definitions which say that the term Social Protection has a broader meaning than the term Social Security. This could be observed in the works of UNICEF and ODI (2009) which refer to social protection as the set of all initiatives, both formal and informal, that provide:

- Social assistance to extremely poor individuals and households. This typically involves regular, predictable transfers (cash or in-kind, including fee waivers) from governments and non-governmental entities to individuals or households aimed at reducing poverty and vulnerability, increasing access to basic services and promoting asset accumulation.

- Social welfare services to groups who need special care or would otherwise be denied access to basic services based on particular social (rather than economic) characteristics. Services are normally targeted at those who have experienced illness, death of a family breadwinner/caregiver, an accident or natural disaster; who suffers from a disability, familial or extra-familial violence or family breakdown; or who are war veterans or refugees.

- Social insurance to protect people against the risks and consequences of livelihood, health and other shocks. Social insurance supports access to services in times of need, and typically takes the form of subsidised risk-pooling mechanisms, with potential contribution payment exemptions for the poor.

- Social equity measures to protect people against social risks such as discrimination or abuse.

These can include anti-discrimination legislation (in terms of access to property, credit, assets, services) as well as affirmative action measures to attempt to redress past patterns of discrimination.

The core components and boundaries of social protection are far from agreed, and different stakeholders perceive social protection in different ways, but no matter the difference in definitions, they all share some common characteristics.

In Ghana, the MMYE developed Social Protection mechanisms to enhance the capacity of poor and vulnerable persons by assisting them to manage socio-economic risks, such as unemployment, sickness, disability and old age. These interventions are meant to improve and increase the livelihoods of target groups by reducing the impact of various risks and shocks that adversely affect income levels and/or opportunities to acquire sustainable basic needs (MMYE, 2007). What is lacking and therefore a gap that is identified in the social protection for orphans and vulnerable children in Ghana is the emphasis of SP particularly meant and targeted OVC as a human right, social justice. Though these laws are embodied in conventions and the national constitution, the enforcement is normally a difficulty and many of these people have their rights infringed upon. The SP seemed to lose its targeting and many of these vulnerable children are left out of the interventions. And apart from the fact that it covers only small geographical areas in Ghana, there is no single intervention that is specific in the protection of orphans or child sensitive. Though donor depended, the capacity of implementing agencies is more than weak and ineffective.2.3. Social Protection in Ghana

Over the past decade Ghana has made impressive progress in stimulating economic growth, reducing poverty and improving governance. Indeed, international assessments of the country frequently herald it as a ‘shining example’ of development not only in West and Central Africa, but on the African continent more broadly.

The history of social protection policies and programmes in Ghana is not a systematic one that shows an evolution of policies and programmes over time (Al-Hassan & Poulton, 2009). Rather programmes have been implemented from various angles by different stakeholders and interests. National development policies in the 1990s have identified the need for the protection of vulnerable groups, but the implementation has not been realized. During Ghana's Independence in 1957 the Government provided free health care services to its population which was solely financed from tax revenues (Abebrese, 2011) However, this was not sustainable due to the fact that the Government of Ghana (GoG) refocused on the financial support of other sectors of the economy. Later on the cash and carry system was established which provided medical treatment solely by a direct cash payment. Before government social protection, there existed traditional systems of Social Protection which were based on kinship, the help and support of the extended family. The extended family arrangement was such that care and support were given to the old, invalid and orphans members of the family; Rural extended family care (Abebrese, 2011; Al-Hassan & Poulton, 2009).

In pre-colonial Ghanaian societies, it was normal for an individual to receive economic assistance from members of his extended family--including paternal and maternal uncles, aunts, grandparents, and cousins. The practice of expecting assistance from family members grew out of the understanding that the basis of family wealth derived from land and labor, both inherited from common ancestors. Even as an individual sought help from extended family members, he was in turn required to fulfill certain responsibilities, such as contributing labor when needed or participating in activities associated with rites of passage of family members. It is because of this mutual interdependence of the members of the family that anthropologist Robert S. Rattray defined the extended family in Ghana as the primary political unit. Today, the same system of welfare assistance prevails in rural areas where more than two-thirds of the country's population resides.

According to Abebrese (2011) with the rise of modern society and the expanding globalization and urbanization the extended family system got weakened. This is in line with Chirwa (2002) social rupture theory. Abebrese indicated that due to the migration of the younger family members into the cities there is a lack of support in the traditional Social Protection Scheme. The family is no more capable to support the diseased and old members of the family on their own. Informal and traditional forms of Social Protection which are based on the above mentioned extended family system or religious networks are normally those which the most vulnerable people have to rely on. Although the more traditional kin-based mechanisms are declining in importance under the influence of urbanisation and demographic changes in Ghana, more formal social protection began after World War II with the introduction of pensions for public employees and formal private sector workers. Formal governments have plans such as the Social Security and National Insurance Trust (SSNIT), however, these plans applied only to people who are employed in the formal sector of the economy. With about two-thirds of the country's population residing in rural areas, and with most urban residents engaged outside the formal economy, the traditional pattern of social security based on kin obligations is relevant and still functions. In rural areas, individuals continue to turn to members of the extended family for financial aid and guidance, and the family is expected to provide for the welfare of every member. In villages, towns, and cities, this mutual assistance system operates within the larger kinship units of lineage and clan. In large urban areas, religious, social, and professionally based mutual assistance groups have become popular as a way to address professional and urban problems beyond the scope of the traditional kinship social security system (Ibid). Though there has been various forms of social protection strategies for the poor and vulnerable in the Ghanaian societies, the below is just some selected social protection programmes after independence.

| Programme/ Strategy | Subject Matter |

| Social Security Act 1965 | Provident Fund Scheme, lumpsum payment for old age, invalidity and survivor`s benefits |

| Social Security Law 1991 | Conversion of the Provident Fund Scheme to a Pension Scheme (SSNIT) |

| Ghana Growth and Poverty Reduction Strategy (GPRS I) 2002-2005 |

Established in order to achieve the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) of the UN |

| National Health Insurance Scheme (NHIS) 2003 | Introduction of a contribution scheme for the Health Insurance to replace the cash and carry |

| Ghana School Feeding Programme (GSFP) 2005 | One hot meal a day for every schoolchild in basic schools |

| Ghana Growth and Poverty Reduction Strategy II (GPRS II) 2006-2009 | Focus on Ghana becoming a middle income country by 2015 |

| National Social Protection Strategy (NSPS) 2007 | Several Social Protection programmes started under the strategy (e.g. LEAP) |

| Livelihood Empowerment Against Poverty (LEAP) 2008 | Social Cash Transfers and free health insurance membership for vulnerable people |

| Source: Adapted from Abebrese (2011). |

All these policies were introduced as a form of protection for the poor in Ghana. Apart from these protections assuming national in nature and hence do not target those who actually need them the most, especially SP designed to target vulnerable children from the three Northern Regions, who are considered to be the most poorest in the country, there is also over politicization of these policies and strategies in Ghana to the extent that the real beneficiaries are neglected in the Ghanaian society.

The research has identified one contemporary theoretical perspective that has so far informed and dominated the OVC response initiatives in Africa and across the globe. This famous theory is the Social Rupture Theory. This session will employ this theory to explain the need for protection for OVC in Ghana and how it has influenced policy of orphan protection and care.

The Theory of Social Rupture : One common observable theme in the OVC literature is the social rupture thesis (Omwa & Titeca, 2011). The Social Rupture thesis argues about how there is a total breakdown in traditional family structures and that the traditional social support systems and safety nets of orphan care is overstretched and eroded and therefore not able to cope with the burden and caring for orphans (Abebe, 2008; Abebe & Aase, 2007). The support systems provided by the family and the communities are collapsing at an alarming rate, due to the strain imposed by the ever increasing number of OVCs. Consequently, the communities are confronted with an increased burden in terms of care and support services for orphans (Chirwa, 2002; Omwa & Titeca, 2011).

Writing on social exclusion and inclusion and reacting to challenges of orphan care and support, Chirwa (2002) argued that there is total breakdown in social support systems, safety nets are collapsing and increasing numbers of orphaned children are becoming destitute. The Theory of Social Rapture understands that various governments should put in place structures that will ease the plight of OVC in societies. Therefore the issue of the need for social protection measures comes in that should respond to the situation of OVC. According to Richter and Rama (2006) families and communities are the first and remain the vanguard, to take action against the worsening conditions of children, and they provide the greatest support system to vulnerable children. Out-of-pocket spending by households, most of whom are already very poor, is the largest single component of overall HIV/AIDS expenditure in African countries; a stark reminder that the economic burden of the disease is borne by those least able to cope. They argue that less than 10 per cent of affected children are receiving assistance from agencies beyond their extended family, neighbours, church, and community (ibid). Subsequently, the lack of or the inadequacy of social protection measures for OVC especially HIV/AIDS orphans in Ghana, has created room for the sporadic orphaned homes and caregiving centers to fill in. Traditionally, according to Richter and Rama, the best place to raise a child is the family however, the breakdown of the family support system led to the establishment of homes and NGOs to operate. Community care strategies support informal, indigenous and traditional ways of caring for children in need of care, most commonly by extended family or kinship members, usually a granny or aunt. This form of informal care is widespread and a practice acceptable in most cultures (ibid 2).

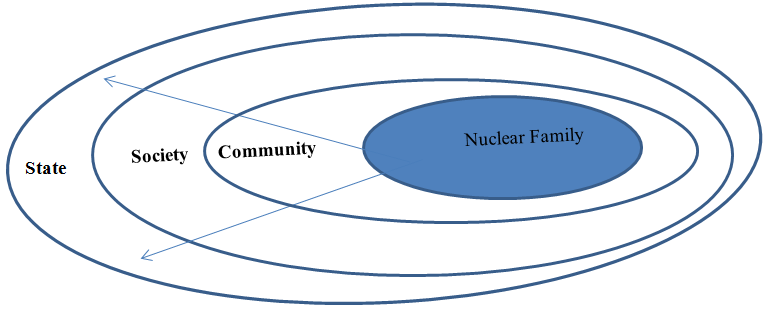

The Social Rupture Theory is best explained by Chirwa (2002) in a presentation from the point of the organisation of the “traditional” childcare system, presented as concentric circles of blood and other family relations. Orphan care is understood to fit into this organization as presented below.

Chirwa (2002) argues that the nuclear family is at the centre of the system, followed by the extended family and the immediate community: the neighbourhood, clan, tribe, and society at large, indicating that the responsibility for the care of children primarily rests with the immediate nuclear family but diminishes as the children grow up towards greater and increasing independence from it. When the nuclear family becomes incapable of providing care, say through disability, impoverishment, parental incompetence, poverty or death, the responsibility is increasingly assumed by the extended family through the “economy of affection” (ibid). Beyond the extended family, comes the community which also has the responsibility for the care of children, the community is explained as usually consisting of the people in the same neighbourhood, or belonging to the same clan or tribe. In Ghana, however, children are valued not only assets for their families alone but the entire community or society and the same is the training and up keep of children. The last but not the least is the state. It provides childcare through a series of measures that include laws, social policies and various welfare programs. Beyond the state is the international regime characterized by legal instruments and human rights standards governing the care of children. However, these rights are supposed to be enforced by governments.

A social rupture is said to occur when a calamity strikes, weakens, and destroys, firstly, the nuclear family or the inner through the death of the principal household heads; secondly, the extended family through the death of alternative care-givers; and then finally the community through the reduced capacity as a result of the escalating number of orphaned children on the one hand and a general reduction on the number of care-providers on the other hand (Omwa & Titeca, 2011). Chirwa says that the effects normally spread outwards to affect society at large (Chirwa, 2002). The impact of HIV/AIDS goes beyond the actual sufferer, and affects all those that are close to him/her. In relation to orphans the impact starts before the actual death of the parent(s). Consequently, many orphaned children end up slipping through the safety nets by dropping out of school, reverting into early marriages or different forms of child labour such as domestic workers or prostitution; or become street children, dropping out of school or delinquents or become destitute (Chirwa, 2002). Other manifestations of social rupture include property grabbing. As Chirwa (2002) puts it, the property is usually being grabbed by immediate family members ironically under the cover of guardianship or the emergence of child, female and grandparent headed households asserted by Abebe and Aase (2007).

When the immediate context in which children live is breaking down and when there is no instant support structure to prevent the children from being at risk, a timely and comprehensive alternative support structure needs to be set in place. Such a structure may cover a (foster) family to care for the child and provide for the basic needs, a community that cares for the family in which the child lives, and advocates for their rights, a government that provides legislation and services that support and protect the child and its (foster) family, and CSOs that provide services in line with the government and advocate for transparency and accountability of institutions and organizations providing these services (Chirwa, 2002; Omwa & Titeca, 2011). The Social Rupture thesis, however, has been criticized for not only adequately answering or guiding OVC development practitioners on key critical issues regarding OVC programming but also being very simplistic although it has been useful in highlighting the impact of adversity on the family and the community (ibid). The linkage between human agency and the structural conditions in a community are inadequately explored. The thesis assumes that there is a linear continuum of care available to orphans that starts from the nuclear family and stretches up to the community and that if one crumbles, the rest follows suite. This assumption has been found to be too simplistic and grossly ignores the fact that the orphan care system in Africa is much more complex and goes beyond looking at the nuclear, extended family and the community (Chirwa, 2002) not forgetting the fact that there are other structural as well as contextual factors that could explain the inability of the communities to provide care and support to orphans which is not only triggered by a single catastrophic event depicted by the Social Rupture Theory. Moreover, the literature on the Social Rupture thesis also looks at the family and the community as homogenous entities which are experiencing difficulties at the same time, in the same pattern, and with the same resource constraints. This assumption has been challenged by a number of scholars. For instance, Abebe and Aase (2007) in their study, profiled Ethiopian extended families into four: rupturing (where middle generation parents are dead leaving care to grandparents), transient (families not presently living in situation of extreme poverty but may easily sink into deprivation), adapting (families in possession of household resources and livelihood assets that can enable to some degree of comfort the absorption of an additional orphan), and capable (families whose material and social capacities as care-givers were found to be viable even in the absence of external material support). The profile of a family therefore indicates the diversities in the resilience of families in adjusting, resisting and coping with the disruptions caused by HIV/AIDS. Thus the traditional orphan care safety net has differential functioning capabilities that profoundly influence the magnitude of care and support an orphan receives.

3. Methodology

3.1. Research Design

The study used the mixed methods research design, employing both qualitative and quantitative research approaches. Creswell (2006) has made strong arguments for mixed methods research that offset the weaknesses of both quantitative and qualitative research as follows; that mixed methods research provides more comprehensive evidence for studying a research problem than either quantitative or qualitative research alone. The strategy permitted the usage of several approaches (Harwell, 2011; Johnson & Onwuegbuzie, 2004) and a triangulation of methods (Nasse, 2018) in addressing the issues.

3.2. The Study Area

Two districts in the Upper West Region constituted the study areas. They were Wa Municipality and Jirapa District, respectively. The criteria for selecting the study districts were based on two issues;

- To get to understand how two different religious dominated areas (Christianity and Islam) perceptions of vulnerable children and the importance of government pro-poor interventions in the areas

- Understand and to examine how government social protection programs for vulnerable children work in the two linguistic and religious areas.

| District | Category | Communities/Department | Number |

Percentage |

| Wa and Jirapa | OVC and Caregivers | Kpongu | 40 |

83.30 |

| Government | DSW, dept. of Children | 2 |

4.20 |

|

| Interventions | GSFP, LEAP, NHIS, Capitation | 4 |

8.30 |

|

| NGO | Child-Support Ghana AGREDS-Ghana |

2 |

4.20 |

|

| Total | 48 |

100 |

3.3. Data Collection Instrument and Sources

Questionnaire and interview guides were used in the data collection. The questionnaire comprised both open and closed-ended items and captured issues around type of support received, adequacy of the support, and impact of support on children in terms of household consumption, income, savings, healthcare and education.

| District | Location of Interview | Description of Informant | Gender |

| Wa Municipal | GSFP | Regional M & E Officer | Male |

| NHIS | Municipal Manager | Female | |

| DSW | Municipal Care and Support Officer | Male | |

| DSW | Regional Director | Male | |

| Department of Children | Regional Director | Male | |

| LEAP (DSW) | Municipal Director | male | |

| Jirapa | NHIS | District Manager | Male |

| GSFP | District Desk Officer | Male | |

| LEAP (DSW) | District Director | Male | |

| Capitation Grant | District Focal Person | Male | |

| DSW | District Director | Male |

| Category | Male |

Female |

Total |

| OVC cared for | 2,177 |

2,712 |

4,889 |

| Aged>65 | 2,005 |

2,299 |

4,304 |

| Severely Disabled | 141 |

213 |

354 |

4. Results and Discussion of the Results

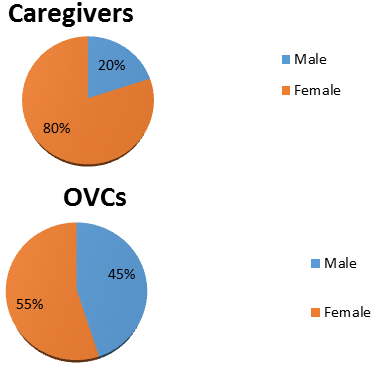

4.1. Sex/Gender of Caregivers and OVCs

As a social category, and in relation to childhood, gender is an important variable at the family level especially when it comes to child care and support. This makes the gender distribution of respondents in the study important for better understanding of what their experiences are in terms of OVC care and support.

Figure-2. Gender distribution of the two categories of respondents.

Wells (2009) argued that gender constructions may leave children at a disadvantage Gender roles and social norms play key roles in determining an individual’s vulnerability, exposure to shocks and access to social protection mechanisms.

Age is a dimension of identity that determines the power relations between an adult and child and how these two influence each other’s existence. Usually, children are expected to be provided for and cared for by adults. Lack of such adults would amount to high exposure of children to various risks making them vulnerable. Results from the survey of caregivers of OVCs indicated that there are enough caregivers to provide for the OVCs but majority of them are advanced in age. See table the following table.

Age |

Caregivers |

OVCs |

1-5 |

- |

1 |

6-10 |

- |

1 |

11-15 |

- |

5 |

16-20 |

- |

10 |

21-30 |

2 |

3 |

31-40 |

3 |

- |

41-50 |

3 |

- |

51-60 |

3 |

- |

61-70 + |

8 |

- |

4.3. Examining Social Protection and Children Vulnerability in Ghana.

All individuals, households and communities are exposed to multiple vulnerabilities that emanate from diverse sources including climate, economic, environment, social exclusion and war. These ultimately cause and deepen the levels of poverty.

This study highlights the need to carefully consider the meaning of “vulnerability” when targeting programs and policies to support children who have been orphaned and rendered vulnerable. Enlisting local community input can help to develop context-specific criteria for the distribution of program resources. Community members in this study proposed characteristics of vulnerability to identify children who are most in need of external support.

The issue of vulnerability was discussed with heads of government departments in child care especially the Department of Social Welfare (district level) and the Department of Children. In order to enrich the data, a discussion is hold on vulnerability with the Regional Director of the Department of Social Welfare.

The concept of vulnerability is not only restricted to individuals, such as children, but is often used to refer to households as well. There is evidence that challenges the assumption that orphans are the most vulnerable children. DSW Officer for Day Care and Case Work looked at vulnerability as:

A vulnerable person is somebody who is in need of help and care or support. Orphans and women as well as people with certain disabilities fall under the group of vulnerable people because of the care and support they need. Orphans are vulnerable because they are supposed to have the care and support of both parents and if one or both parents are not there, they miss that care and support (Interview, 12/04/2013)

He mentioned again that women were also vulnerable because of their physiological and biological make up. He said:

They are confined to the house taking care of household chores while the men work. The men are thus higher than the women because they (men) provide the needs of the family and take all the decisions while the women have no say. In times of violent conflicts at home, it is the women who suffer most. Women are thus biologically and physically vulnerable (DSW Officer for Day Care and Case Work, 12/04/2013)

However, the Regional Director of the department of Children of the Upper West region looked at vulnerability to include men. He said “Men are also vulnerable because in our society, men are supposed to have the upper hand than women but in some cases particularly where women are the bread winners, the women have the upper hand and in that case the men are vulnerable” (Interview with Regional Director of the Department of Children, 15/04/2013).

According to the Director, the causes of the vulnerability of children are the death of parents and in some cases, the irresponsibility of the parents. Parents could be alive and the child classified as vulnerable for example as a result of some preventable diseases.

I found Bolin’s and Stanford/s (1998) definition of vulnerability to be most appropriate in this study. They argue that vulnerability concerns the complex of social, economic, and political considerations in which peoples’ everyday lives are embedded and that structure the choices and options they have in the face of environmental hazards. The most vulnerable are typically those with the fewest choices, those whose lives are constrained, for example, by discrimination, political powerlessness, physical disability, lack of education and employment, illness, the absence of legal rights, and other historically grounded practices of domination and marginalization. Children however, face different vulnerability scales from adults due to their special position in society. They have not developed physically and psychologically to be able to deal with various forms of vulnerability. Children’s dependence on adult caregivers and their voicelessness make them passive beneficiaries of coping mechanisms employed by adults, which may not necessarily address their plight.

The Officer for Day Care and Case Work at the DSW indicated that the peculiar situations that made orphans in the Wa Municipality vulnerable largely included the absence of parenting. Most of these children had lost one or both parents and did not have the benefit of growing up from a complete home and enjoying parental love and care. They were often denied access to education, health care and other basic necessities in life because of the absence of the parents.

The understanding is that apart from orphans, women and the disabled who were mentioned as the most vulnerable, parameters such as lack of health care, education and other basic necessities were used as proxies for vulnerability. Poor peoples' conceptions of poverty often correspond closely to the notion of vulnerability. According to Smart (2003) the link between poverty and vulnerability seems well established, suggesting that policies to tackle poverty will have a positive impact on OVC. The day care and case work officer of DSW indicated that poverty could also make parents to abandon their children because of the fear of failure to take care of the children knowing very well that once the child is discovered, he or she would be taken to the custody of the Department of Social Welfare for the necessary care. He said: “Most young people though not married and not capable of caring for a child are misled by things they see in the media into sexual relationships and when pregnancies occur, a key option they consider is abandonment” (DSW Officer for Day Care and Case Work, 12/04/2013)

In response to whether the issue of OVC is increasing or decreasing, the day care and case work Officer of the DSW said:

Comparing the past to now, the prevalence of orphans and vulnerability is increasing because when I started work here in 2004, there were just about 3 of such cases including two abandoned children and one who lost the mother but right now, we have many of such cases with five of them coming in this year alone. Even though death which we can neither explain nor control is responsible for the upsurge in orphans, our attitudes and way of life are also largely responsible for that. This year alone, we got about four abandoned children. We lost two of them unfortunately but some Americans are going through due process to adopt the other two and take them to the States” (Interview, 12/04/2013)

Abandonment can be traced to a lot of factors including denial of the pregnancy by the man responsible for it. Under such circumstances, the woman will abandon the child as an option for reducing her burden.

However, the Director of the Department of Children indicated that they were limited in assessing whether the situation of OVCs in the region was getting worst or better because there had not been any in-depth analysis carried out. He said:

We still cannot determine whether there are more orphaned children now than before because we have not done any in-depth analysis of the situation but we can say their condition is worse based of the stigma and discrimination they suffer. Orphaned children are mostly at a disadvantaged side in the sense that, there is so much stigma especially if they got orphaned as a result of their parents dying out of HIV/AIDS and their conditions are usually not the best looking at the discrimination and stigma they suffer in their communities. Sometimes even the family members who are supposed to take care of them reject them because of the way and manner their parents died. The prevalence of the HIV/AIDS in the Municipality fluctuates but one can always imagine the number of children orphaned as a result of deaths through HIV/AIDS which is not the best” (Regional Director of the Department of Children, 15/04/2013).

In discussing vulnerability among OVCs for social protection, identifying first and foremost the sources of the vulnerability is as important as the solution. During the discussions with respondents, it was clear that one source of vulnerability of OVCs was HIV/AIDS infection. The incident is fast increasing in the Upper West Region and many children are becoming vulnerable due to the death or sickness of their parents. It was also clear that social class is another source of child vulnerability. In a bid to fit in and do the same things their peers are doing, children may encounter peer pressure which may make them adopt negative coping strategies in order to fit in. They may resort to stealing, casual and unprotected sex, and, alcohol and drug abuse amongst others. When all these factors and more, intersect in intricate ways, with HIV/AIDS being the pivotal point, and within the context of orphan hood the vulnerability is heightened even more. It is probably because of these that HIV orphans are considered as (more/most) vulnerable children.

The DSW eligibility criteria offer the advantage of mapping out vulnerability for the benefit of social protection such as the LEAP program as an efficient way to distribute resources.

4.4. The Situation of OVCs in the Upper West Region

Technically, children are people under the age of 18 years and according to the laws of Ghana, this is a group of people who do things without knowing what they are doing. For example when we have children coming into contact with the law, they are treated differently. This was the starting remarks of the Regional Director of DSW. Upper West Region as the last of the ten regions to be created in Ghana has a lot of challenges one being poverty. The Region is the poorest and being poor means the people will not have all the required resources to take care of their children. The bottom line of most cases of children neglect is poverty.

There are also some socio-cultural practices which are inimical to the development of children in this region. According to a respondent, “even though there is a law against Female Genital Mutilation (FGM), people are still doing it under cover and we are told that the practice is very common with settler communities” (Regional Director of DSW, 16/04/2013). This is an indication that child protection should go beyond merely extending social protection to children and should respond to the child protection issues such as prevention of violence in general which mostly affect children, exploitation and abuse against children, including commercial sexual exploitation, trafficking, child labour and harmful traditional practices, such as female genital mutilation/cutting and child marriage.

According to the Regional Director of the DSW, there are other practices like the situation in the Tabiesi community where people do not encourage girl-child education because of their cultural beliefs. The belief is that the dowry of a girl child is received by the maternal uncle in which case there is no need investing in the girl-child once somebody else will take the dowry, thus making children especially the girl-child not to be sent to school.

He further indicated that cases of defilement are still very rampant in the Region, giving an example of a man defiled four girls last year and only God knows how many girls he would have defiled in the past. Though a young Region, there are a lot of problems facing children. The extended family system is broken down, and indeed it was the extended family that used to take care of OVCs but with modernization and urbanization. The HIV/AIDS prevalence has also produced a lot of orphans in the region and that is why the LEAP programme is of so much importance. Presently, LEAP exists in all the 11 districts but not in all the communities. One would really come to terms with the reality of the HIV/AIDS problem in places such as Lawra and Nandom, where support groups of people living with HIV/AIDS are established. The plight of orphaned children is therefore an emerging social problem to be tackled with all seriousness. Before now, a child who lost the mother had another mother in the home because other women would offer to care for them. There was also support from extended family members.

Subbarao, Mattimore, and Plangemann (2001) wrote that fostering of orphans by relatives is more attuned to the African socio-cultural milieu than most other options. This is also the option widely prevalent across much of Africa. Orphans are being looked after by the extended family or friends and relatives known to orphans. However, care needs to be taken that fostering does not lead to child abuse. Accordingly, mistreatment appears to be confined largely to stigmatization and in some instances discrimination in food allocation, education, and workload. This was also observed by the Regional Director of DSW that fosterage used to be an important source of social protection.

Even what came to be known as “bye-election” (when a brother dies and another brother takes on the widow and children) was and is still a social protection mechanism that has been practiced in most of the northernpart of Ghana.

Statistics from the Ministry of Women and Children Affairs revealed that Upper West Region is considered as one main sending sources of Kayaye (head porters) and chop bars workers to Accra and Kumasi. The region is very vulnerable due to its poverty level, breakdown of the extended family support system, and lack of fosterage.This has made the situation of OVCs in the region worsening on daily basis and there is no clear statistics as to how many OVCs are in the region. Though there are some private NGOs working to support OVCs, their activities are project and donor based and thus not permanent and rather reach out to limited number of OVCs. Government social protection interventions are therefore very necessary in the region to support in the areas of education, health, food and nutrition and psychosocial services. Income generating activities at the family level is very important especially targeting women with micro-credit to better support their OVCs

4.5. Understanding Social Protection: The views of Respondents

As a conceptual approach, social protection offers a way of thinking the requirements of groups and individuals to live a fulfilling life, the role of the state in facilitating this, and the vulnerabilities of particular groups or individuals. As a set of policies, social protection consists of interventions which address vulnerabilities and factors which hinder a group or individual's capacity to enjoy a fulfilling life. Social protection is concerned with people who are vulnerable or at risk in some way, such as children, women, elderly, disabled, displaced, unemployed, and the sick, and with ways of transferring assets to these vulnerable groups (Scott, 2012).

To assess interviewees’ understanding of social protection, the Regional Director of DSW indicated that:

It has come to be understood that when a country grows more affluent in terms of GDP, the standards of living of the people also changes but contrary to that, it has now been established that the more affluent a country is in terms of GDP, the more deplorable the livelihood of the people and that is why Ghana’s oil find is seen by some people as a curse. It is under these conditions that the state has to intervene by giving social protection. So social protection is meant to support the most vulnerable within the country or society and for so many years now, the government of Ghana has been doing that. (Interview, 16/04/2013)

Social protection is directly related to poverty and according to the respondent, the north is very poor and one needs to go into the rural communities particularly during the lean season in order to ascertain the reality of the situation. The Regional Director of DSW said: “When we were doing the poverty mapping of the Upper East Region we were told of a community where during the lean season when they had planted and invested every resource into the farm, the women would cook “stones” in the night just to keep the children in hope till they fall to sleep” (Interview, 16/04/2013). This is just to emphasize the point of poverty in relation to social protection and indeed the women and children bear the brunch of it.

Childhood poverty is unacceptable. The Director said it is because of childhood poverty that interventions like the school feeding programme, free exercise books and uniforms and the LEAP programme which is Ghana’s commitment at meeting the first of the UN Millennium Development Goals by 2015 were introduced. Because of the LEAP and other interventions, Ghana has already attained middle income status ahead of 2015. He mentioned that in the past some of these policies were either nonexistent or were poorly implemented. It is important therefore that the new Ministry of Gender, Children and Social Protection is trying to bring all social protection programmes together for proper coordination which will surely be of immense value to Ghanaians.

Responding to the issue, the Director of Children said social protection is about measures that will protect people against risks and vulnerabilities especially people who find it difficult to meet their three square meals a day. He mentioned people in such category to include, children, women, and people with disabilities, the aged and people in conflict prone areas.

According to the Director of Children:

Social protection for children is a laudable idea and there are a number of interventions put in place e.g. the capitation grant, NHIS, provision of school uniform and the school feeding programme are all interventions put in place to reduce child poverty and enable parents to send their children to school so indeed these social intervention policies are making a great impact in the lives of children (Interview with the Regional Director of Children, 15/04/2013).

From the understanding of the two respondents, social protection is an inevitable concept that should be introduced to all segments of society. As the society becomes more affluent, the gap between the rich and the poor widens and if governments do not introduce safety measures for the poor in the society, there will be unrest and societal chaos. According to the Director of DSW, it is because of this that Europe and the Americas have introduced unemployment pay such that the unemployed will be able to meet their daily basic needs requirement.

5. Conclusion and Implications

The research concluded that though Ghana has over the years implemented a number of social protection interventions for the poor and vulnerable in the society, the poor and vulnerable are barely touched by these interventions.

The very basic factor to this is the lack of political will and commitment to addressing the issue of social protection for vulnerable children. This is reflected in government failure to resource the departments and agencies which are mandated by law to provide the rather complex issue of social protection for the right target.

The delays in release of funds for the payment of the LEAP cash grant programme which is currently due over 8 months coupled with the lack of logistics for DSW to even carry out other non-material aspects of the social protection measures in beneficiary communities is a clear indication of government insensitiveness and lack of commitment to issues of social protection for our most poor and vulnerable in the society. This implies that governmental authorities should continue to put some tremendous efforts in eradicating extreme poverty (Nasse, 2019) by some policies that reach out to the right needy people at the right time.

References

Abebe, T. (2008). Ethiopian childhoods: A case study of the lives of orphans and working children. Thesis Submitted for the Award of Degree of Philisophiae doctor. Stockholm, ST: Norwegian University of Science and Technology, Faculty of Social Science and Technology Management, Department of Geography, Norwegian Centre for Child Research, Trondheim (unpublished).

Abebe, T., & Aase, A. (2007). Children, AIDS and the politics of orphan care in Ethiopia: The extended family revisited social science and medicine. Addis Ababa, AA: Ethiopia 2058-2069.

Abebrese, J. (2011). Social protection in Ghana: An overview of existing programmes and their prospects and challenges. Accra, AC: Friedrick Ebert Stiftung.

Al-Hassan, R., & Poulton, C. (2009). Agriculture and social protection in Ghana (Growth and social protection working paper 04. Accra, AC: Future Agricultures and Centre for Social Protection.

Chirwa, W. C. (2002). Social exclusion and inclusion: Challenges to orphan care in Malawi. Nordic Journal of African Studies, 11(1), 93-113.

Creswell, J. W. (2006). Qualitative inquiry and research design. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Greenblot, K. (2008). Social protection for vulnerable children in the context of HIV and AIDS moving towards a more integrated vision. Working Paper for the Inter-Agency Task Team (IATT) on Children and HIV and AIDS Working Group on Social Protection.

Greenblott, K. (2007). Social protection in the era of HIV and AIDS. Examining the role of food-based interventions. Rome, RO: Occasional Paper No. 17. World Food Programme.

Handa, S., & Park, M. (2012). Livelihood empowerment against poverty program: Ghana baseline report. Carolina, CA: Carolina Population Center, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

Harwell, M. R. (2011). Research design in qualitative/quantitative/mixed methods. Thousand Oaks, CA: University of Minnesota/Sage Publications.

Inter-Agency Task Team. (2008). Social protection for vulnerable children in the context of HIV and AIDS. Working Group on Social Protection: Working Paper.

Johnson, R. B., & Onwuegbuzie, A. J. (2004). Mixed methods research: A research paradigm whose time has come. Educational Researcher, 33(7), 14-26. Available at: https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189x033007014.

Jones, N., Ahadzie, W., & Doh, D. (2009). Social protection: Opportunities and challenges in Ghana. ACCRA, AC: ODI, UNICEF.

MMYE. (2007). The national social protection strategy: Investing in people. Accra, AC: The Government of Ghana.

Nasse, T. B. (2018). Religious practices and consumption behavior in an African context: An exploratory study on consumers in Burkina Faso. Doctoral Thesis, Aube nouvelle University, Cheikh Anta Diop University, Ouagadougou, OU.

Nasse, T. B. (2019). Alcohol consumption and conflicts in developing countries: A qualitative and a quantitative research concerning Christian consumers in Burkina Faso. African Journal of Business Management, 13(15), 474-489.

Omwa, S. S., & Titeca, K. (2011). Community-based initiatives in responses to the OVC crisis in North and Central Uganda. Brussels, BR: A Discussion Paper Belgium.

PEPFAR. (2006). Orphans and other vulnerable children programming guidance for United States Government–Country Staff and Implementing Partners. Office of the U.S. Global AIDS Coordinator, publish-United States of America.

Richter, L. M., & Rama, S. (2006). Building resilience: A rights-based approach to children and HIV/AIDS in Africa. Stockholm, ST: Save the Children.

Sabates-Wheeler, R., & Pelham, L. (2006). Social protection: How important are the national plans of action for orphans and vulnerable children: Institute of development studies and UNICEF. Brighton, BR: University of Sussex.

Scott, Z. (2012). Topic guide on social protection: Governance and social development resource centre (GSDRC), International development department, published by college of social sciences. Birmingham, BI: University of Birmingham.

Smart, R. (2003). Policies for orphans and vulnerable children: A framework for moving ahead. USAID and POLICY. Washington D.C: POLICY Project.

Subbarao, K., Mattimore, A., & Plangemann, K. (2001). Social protection of Africa’s orphans and other vulnerable children. Issues and good practice program options. Africa region, the World Bank. Human Development Working Paper Series. Washington D.C: The World Bank.

UNAIDS. (2004). Report on the global HIV/AIDS epidemic. Geneva, GE: Joint United Nations Program on HIV/AIDS.

UNICEF, & ODI. (2009). Social protection to tackle child poverty in Ghana. A briefing paper on social policies. Accra, AC: UNICEF.

Wells, K. (2009). Childhood in global perspective. Cambridge, CA: Polity Press.