Performance of Family Business in Malaysia

Aissa Mosbah1

Sultan Rehman Serief2

Kalsom Abd Wahab3

1,3Faculty of Economics and Muamalat, University Sains Islam Malaysia.

2Faculty of Business Management and Professional Studies, Management and Science University, Malaysia.

|

Abstract

Performance of family firms is an interestingly growing topic of study. In Malaysia, many studies were conducted in an attempt to understand performance of family firms, however these studies have been biased towards operationalizing performance through financial indicators particularly Tobin’s Q. Researchers also tended to test the effect of various factors relating to corporate governance and board of directors on performance. Ethnic wise, performance of family firms may be significantly impacted by culture. Success of Chinese firms seems to be attributed to the role of family participation and ethnic networks governing the entrepreneurial practice. |

Licensed:

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License. |

Keywords:

Performance

Family

Firms

Businesses

Malaysia

Malays

Indian

Chinese. |

| (* Corresponding Author) |

1. Introduction

Family business and entrepreneurship are frequently linked together. Entrepreneurship functions as the “means” to the family firm “end” of long-term existence, growth, and renewal (Goel & Jones, 2016). Family businesses make up the largest ownership form in most countries. According to Forbes website, citing the Centre for Family Business at the University of St. Gallen, Switzerland, family firms constitute 80-90% of businesses stock worldwide and contribute significantly to GDP and jobs. Alone, the world top 500 family businesses generated US$6.5 trillion and provided 20.9 million jobs in 2013.

The magnitude and impact of these firms have led to the emergence and growth in research that deals with this type of firms (Kraus, Harms, & Fink, 2011; Short, Sharma, Lumpkin, & Pearson, 2016; Zahra & Sharma, 2004). While research in family business has been recently recognized as a global phenomenon that is rapidly growing across many disciplines and outlets, it boomed to unprecedented levels and was accompanied by a quality research output (Craig, Moores, Howorth, & Poutziouris, 2009; Short et al., 2016). In Malaysia, family business studies have recently become more prevalent, and a number of studies have focused on factors that determine the levels of family business performance (Ghee, Ibrahim, & Abdul-Halim, 2015). Given this fact, there is a need to review the available studies on performance of family firms in Malaysia in order to provide an assessment to the state of affairs related to performance research. The current paper is an endeavour towards this objective. The paper tries to identify research trends in terms of performance operationalization, common explanatory factors tested for their effect on performance, and findings. It is also within the scope of this paper to discuss performance variations among Malay, Chinese and Indian family firms to draw some useful conclusions.

2. Family Business in Malaysia: Characteristics

Statistics on family firms in Malaysia are not easily identifiable; however, there scattered information related to the phenomenon can give a good idea about its magnitude. Malaysia’ family businesses make up about 70% of the listed firms and contribute tremendously to GDP (Amran & Ahmad, 2010). They are often small in size (Set, 2013), mostly owned by Chinese (Abdullah, Abdul, & Hashim, 2011; Amrann & Ahmad, 2011). Historically, these companies evolved from traditional family-owned enterprises and prefer to follow culture and management style of the business founder with not much openness western business practices and modern management skills (Nee, 2007). A study conducted by Price Waterhouse Coopers – PWC (2016) noted that some companies are managing their strategic planning effectively while other are stuck with daily business issues and inter-generational aspirations. The study also indicated that Malaysian family businesses share strong attachment to their respective cultural values, while their key challenges are centred on succession planning, innovation and talent attraction and retention. With respect to Chinese firms, corporate governance is anchored in the traditional management approaches and increasing new/western management skills that are implemented by new generation managers (Nee, 2007). Besides, the teachings of I-Ching, Confucianism and Taoism are crucial to the day to day management practices (Goh, 2008; Nee, 2007). Although succession planning is an important practice for the development and continuation of family firms, not all Malaysia family firms are considering it. This was evidenced in the both studies of Abdullah et al. (2011) and PWC (2016). These studied respectively noted that only half and less than one third of the surveyed businesses have succession plans. In the same time, the main planning actions include: transferring management to the next generation, transferring ownership and hiring professional management, and selling/floating the business (PWC, 2016). According to Abdullah et al. (2011) successor characteristics and succession issues are some of the key determinants of succession plans.

The overall context within which family firms in Malaysia operate has also been shaped by the intervention of the government in the economy under the British ruling and after the independence. In the post-independence era, the governments implemented affirmative actions through what was is known as the “New Economic Policy”. The new policy aimed to reduce racial imbalances and boost the economic and social wellbeing of Bumiputras (Indigenous Malays) through concessions in terms of grants, trade, education and certain jobs (Haniffa & Cooke, 2002). In the meanwhile, these actions had multiple bearings on ethnic participation, inter-ethnic partnership, and firm development (Gomez, 2007; Haniffa & Cooke, 2002) and resulted a certain change in the ethnic business structure. For example, by 1970, Indians controlled around 1.1 per cent of total corporate equity, Malays controlled 2.4 per cent and Chinese owned 27.2 per cent. However, thanks mainly to these actions, Malay corporate equity increased to 19 per cent in 1990 while Indian ownership increased went up to 1.2 per cent in 2004 and to 1.6 per cent in 2008 (Xavier & Gomez, 2018).

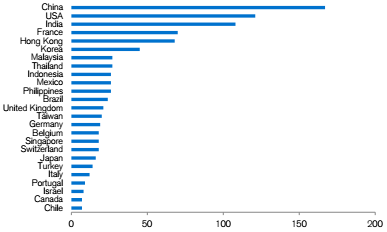

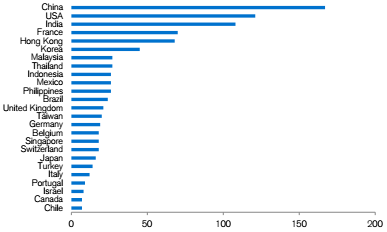

Figure-1. To 25 countries per Family-owned firms.

The development of family firms in Malaysia yielded not only a numbers of tycoons across different sectors (Ibrahim & Samad, 2010) but also several firms that are competing regionally and globally. As depicted in Figure 1, the Credit Suisse Research Institute’s (CSRI) report ranked Malaysia seventh globally in 2017 with regards to the number of family-owned companies (CSRI, 2017). CSRI report also ranks two Malaysian family firms high. Press Metal; a company that operates in the aluminium industry, ranked 49 globally and 32 in Asia in terms of revenue growth (24% on average) and 44 in Asia in terms of share-price return (30% on average). Genting Hong Kong, which is a member of the Malaysian Genting Group, also ranked 29 globally and 20 in Asia in terms of revenue growth (32% on average).

3. Research on Performance of Family Businesses in Malaysia

Scholars have tried to unveil many aspects of family entrepreneurship in Malaysia. Thus, they explored a variety of topics including, inter alia; performance (stressed in this study), earnings (Jaafar, Kieran, & AbdulWahab, 2012), business inheritance and succession (Abdullah et al., 2011; Amran, 2012; Ghee et al., 2015), corporate social responsibility, IFRS mandatory disclosure (Abdullahs, Evans, Fraser, & Tsalavoutas, 2015), corporate social responsibility (Yusof, Mohd-Nor, & Hoopes, 2014), CEOs language choice (Ting, 2017), and internationalization (Cheong, Lee, & Lee, 2015). The next sub-sections will specifically shed light on the operationalization of performance as found in empirical studies in the Malaysian context, the factors assessed in their effect on performance and how performance of this type of businesses is shaped. The last part will also draw on ethnic variations in terms of performance between Malay, Chinese and Indian family firms.

Table-1. Operationalization of performance and factors influencing it: recent empirical literature.

| Study |

Operationalization of performance |

Common explanatory variables of performance |

Key findings |

| Amran and Ahmad (2009) |

firm value (measured by the q-value) |

Board independence, Board size, Leadership structure, CEO tenure, Firm size, age, Sales growth, Leverage, Return on assets, Asset tangibility. |

Board size and leadership structure impact the firm value but corporate governance mechanisms do not. |

| Amran and Ahmad (2010) |

Tobin’s Q |

Family, ownership, director qualification, age, education level, gender, generation, Generation, Debt, Firm age, Firm size. |

Family ownership affects performance positively. founder-managed firms have lower firm performance than successors-managed firms, while old managers perform lower than their younger counterparts. |

| Zainol and Ayadurai (2010) |

Firm performance (Sub*: profit growth before tax, sales growth rates, market share, overall performance) |

- Cultural background of the entrepreneur

- Entrepreneurial orientation (Mediator) |

In Malay firms, cultural background is a significant predictor of performance in Malay family firms. However, the entrepreneurial orientation (EO) is not found to be a mediator of this relationship. |

| Amrann and Ahmad (2011) |

Firm performance (Tobin’s Q, earnings per share, operating cash flow) |

No of directors, % of independent non-executive director, % of directors with degree, % of directors with professional qualification, total directors, Book value of long-term debt/total assets, age. |

Firms with duality leadership, large board size, low directors’ expertise and contribute positively to performance. Academic qualification of directors, on the other hand, does not influence performance |

| Ibrahim and Samad (2011) |

Firm performance (Tobin’s Q, return on assets, and return on equity) |

No of directors on the board, % of independent non-executive director/ total directors, % of directors with degree/ total directors, % of directors with professional qualification/ |

- Board size, duality, and independent director have strong and significant effect on performance.

- Family firms experience higher ROE value than non-family firms but lower Tobin’s Q and ROA values |

| Zainol and Ayadurai (2011) |

Firm performance (Sub: profit growth, sales growth, market share, overall performance) |

- Personality traits

- Entrepreneurial orientation (Mediator) |

There is a relationship between personality traits of Malay family firm and performance but entrepreneurial orientation does not have the power to mediate this |

| Azizan and Ameer (2012) |

Firm performance (profitability, cash flows, short-term investments, total debt, and dividends) |

Shareholder activism (as led by the

Minority Shareholder Watchdog Group (MSWG)) |

There is no consistent positive impact of MSWG engagements on the abnormal returns over the years. After one year of MSWG intervention, significant differences between performance of MSWG family and non-family firms were not found. |

| Ghee et al. (2015) |

Firm performance (unspecified) |

- Management style, family members’ relationships, Job and family values, Preparation level of heir.

- Succession issues and succession experience (Mediators) |

The managerial style, family members’ relationship, values and beliefs as well as preparation level of heir’s effect family firms’ performance. Succession issues and succession experience have partial and full mediation effect |

| Yeoh (2014) |

Firm performance (Sub: total sales growth, export growth, and export profitability growth. Satisfaction) |

- internal and external technology sourcing modes,

- Internationalization and outsider CEO (Moderators)

- Innovations (mediator). |

Functional and process upgrading strategies depend on the internal and external sourcing strategies of the firm and is moderated by the international level of experience of the outside CEO. |

| Zainol (2013) |

Firm performance (Subjective - 4 items: profit growth before tax, sales growth rates, market share, overall performance) |

- Personality traits, cultural background, and government aid programs

- Entrepreneurial orientation (Mediator) |

Although entrepreneurial orientation (EO) significant predict Malay family firm performance, it does not mediate the relationship of cultural background, personality traits, and government aided programs with firm performance. |

| Gohs and Rasli (2014) |

Firm performance (market-to-book ratio as proxy) |

- CEO duality, and board independence

- Corporate governance mechanisms (Moderator) |

Monitoring is strengthened by board independence in non-dominant large shareholders. Family owners prioritize firm control but do not utilize CEO duality to diminish the monitoring of non-dominant large shareholders. |

| Liew, Alfan, and Devi (2015) |

Firm performance: firm value (Tobin’s Q and market-to-book value, ROA, ROE). |

- RPTs that are likely to result In expropriation,

- Ownership concentration (Moderator) |

RPTs decreases family firm value but this relationship is moderated by controlled shareholders’ ownership. Besides, compared to non-family firms, expropriation via RPTs is stronger in family firms |

| Ung, Rayenda, and Chin-Hong (2016) |

Firm performance (Tobin’s Q, Return on assets) |

Retrenchment )measured through the

reduction in assets and costs ( |

Retrenchment has positive impact on financial performance but negative impact on accounting performance. |

| Mokhber, Abdul-Rasid, Vakilbashi, Mohd-Zamil, and Woon (2017) |

Firm Performance (Subjective – 4 items: profitability, revenue, growth, and return on investment) |

preparation of heirs, relationship between family and business members |

Both heirs level of preparation and the relationship between family and business members have positive impacts on the performance of family business. |

Table 1 summarizes fourteen empirical studies on performance of family firms and looks at how performance is operationalized as an outcome variable. It also lists the different explanatory factors tested for their effect on or ability to predict performance. The table further presents the key findings reported in these studies. Notwithstanding these mostly do not specify the ethnic affiliation of the target frim, whereas other few studies tended to focus on only one ethnic group. This is true for the following studies that addressed Malay family businesses; (Zainol & Ayadurai, 2010, 2011) and Zainol (2013).

Many of these studies rely on firms listed in the Malaysia Stock Exchange (MSE) where access to data is facilitated. Given the nature of data available in the MSE and firms’ annual reports, performance was, in most cases, measured through financial indicators. Firm values proxied in Tobins’ Q was widely employed. Tobins’ Q is regarded as a good measure of firm performance (Mayer, 2003) because it reflects market performance rather than accounting performance (Amran & Ahmad, 2009).

Other measure of performance in form of financial/metric data included market-to-book ratio, cash flows, short-term investments, total debt, dividends, return on investment, earnings per share, operating cash flow, return on assets, and return on equity. In line with this, researchers also gauged performance through subjective measures that reflects perception and satisfaction of the owners/directors regarding financial indicators such as profit growth, sales growth, market share as well as the overall performance of the business. Although subjective/perception measures are less powerful than ratio/metric measures, they represent a good quantifiable alternative in business research and yield reliable results.

As we shall see in the empirical studies summarized in Table 1, factors related to corporate governance and attributes of the board of directors were widely used as explanatory variables or factors that influence performance of family businesses. Other variables that were tested on their effect on performance include the family attributes, director characteristics, firm characteristics, financial attributes, culture and shareholders. Ramchandran (2012) posits that the observed bias towards researching corporate governance in family business is due to its positive effects in introducing greater level of professionalization.

4. Ethnic Variations in Family Business Performance

Ethnic wise, there are apparent variations entrepreneurship and performance among Malay, Chinese and Indian family firms. Earlier, we highlighted how government policies influenced the economic participation of the main three ethnic groups. Another factor that adds primarily to these variations is culture. Zainol and Ayadurai (2011) provided a good discussion on the link between Malay culture and entrepreneurship perception in general. The gist of this discussion can be summarized in the following four attributes/factors that have reverse effects on business and performance: 1) conservatism, risk aversion and lack of initiatives, 2) unproductive and underdeveloped attitude towards money, 3) attitudes towards wealth; land but other properties are considered as capital asset for investment, 4) Misconceptions regarding the concept of “Takdir”. To what extent business performance can be impacted by such attributes is not known. Evidence on additional attachment of Malay people to the Islamic principles was found in the study of Othman, Ghazali, and Cheng (2005). These authors found that Malay entrepreneurs show higher satisfaction from working hard and seeing the job well done as compared to the Chinese. Work perfection is indeed well recommended in Islam.

For Chinese, a different set of cultural values with different implications on business performance are expected. Chinese family business style is anchored in the Confucian principles. The latter influences the organizational structure and business practices significantly (Redding, 1990) In fact, Chinese businesses follow a strong collective identity and work within a network of business relationships (Tsang, 2001). According to Sin (1987) and To (2010) factors like strong family ties, sharing and pooling of resources, efficient use of labour, thrift, operations flexibility, paternalism, obedience to the manager owner, high centralized decision making and loyalty add strength to Chinese family firms and boost their performance. However, these same factors may weaken performance when the business grows larger. In line with this observation, Carney (1998) attributes the success of Chinese family firms to the relatively simple ‘personally managed’ entities that are operationally contained in a network of connections. The spread and success of Chinese family firms is noticeable across the whole South East Asian region where they controlled over 70 % of the corporate wealth in 1995 despite the fact that they constituted only 6% of the total population (Backman, 1995).

With regards of Indian family firms, a little is known, however, the existing evidence shows that unlike the Malay and Chinese firms, Indian businesses have remained one-store operations, with little diversification and expansion. Similarly, Indian entrepreneurs remained conservative and largely cautious of expansion due to the competitive industry (Gomez 2001 as found in Amrann and Ahmad (2011)), but perhaps also to keep their businesses unnoticeable and avoid reverse policy actions (Gomez, 2007; Whah, 2007). According to (Ramchandran, 2012), Indian family firms may be stuck in their choice between of risks and returns of business growth on the one hand and conservation of wealth of the family on the other hand.

Besides, one of the cultural components that weight in entrepreneurship and business performance is uncertainty avoidance (Broekhuizen, Giarratana, & Torres, 2017; Swierczek & Ha, 2003). Although Malaysia scored moderately low (36) in Hofstede uncertainty avoidance index, differences between the main three groups exist (Haniffa & Cooke, 2002; Zainol & Ayadurai, 2011). In fact, Hofstede indexes of cultural dimensions do not reflect ethnic differences in Malaysia properly. Haniffa and Cooke (2002) proposed the use of scores of Indonesia (48) and Hong Kong (29) instead because these scores may be more accurately applied to Malays and Chinese respectively. Similarly, scores of India (40) and/or Sri Lanka (45) may provide better level of uncertainty avoidance among Malaysian Indians.

Uncertainty avoidance refers to the level of tolerance for ambiguity and uncertainty (Wennekers, Thurik, van Stel, & Noorderhaven, 2007) and have implication on individual entrepreneurial intention, engagement and operations (Broekhuizen et al., 2017; Hancıoğlu, Doğan, & Yıldırım, 2014). Operating under uncertainty conditions boosts the ability of entrepreneurs through motivation and risk-taking tendency (Hancıoğlu et al., 2014). Wennekers et al. (2007) further posit that entrepreneurship would be unnecessary in the absence of uncertainty. In Malaysia, Chinese family firms are rated low on uncertainty avoidance, because of their greater acceptance of challenges and willingness to tackle greater risk (Abdullahp, 1992). Under such condition, they tend to show not only high propensity towards entrepreneurial engagement but also high tendency towards taking actions that aims to boost performance such as investments, marketing campaigns and so on.

5. Conclusion

This paper addressed performance of family businesses in Malaysia. Empirical studies that were conducted to examine factors influencing performance have majorly built on factors derived from the corporate governance and board of directors. Besides, performance as a concept has often been measured through financial indictors particularly Tobin’s Q ratio. Similar to research in finance and entrepreneurship, common financial indicators like return on assets, return on investment, market-to-book value as well as subjective measurement gauging satisfaction of the owners/managers have been noticed as well. From ethnic perspectives, differences in performance of Malay, Chinese and Indian family firms are observed. While both culture and government policies seem to have impacted entrepreneurial engagement, performance may be significantly impacted by culture. Success of Chinese firms is attributed to the role of family and ethnic networks governing the entrepreneurial practice. Not much is known about Indian family firms due to lack of research.

References

Abdullah, M. A., Abdul, H. Z., & Hashim, J. (2011). Family-owned businesses: Towards a model of succession planning in Malaysia. International Review of Business Research Papers, 7(1), 251-264.

Abdullahp, A. (1992). The influence of ethnic values on managerial practices in Malaysia. Kuala Lumpur: Malaysian Institute of Management.

Abdullahs, M., Evans, L., Fraser, I., & Tsalavoutas, I. (2015). IFRS mandatory disclosures in Malaysia: The influence of family control and the value (ir)relevance of compliance levels. Accounting Forum, 39(4), 328-348.

Amran, N. A. (2012). CEO succession: Choosing between family member or outsider? Asian Journal of Finance & Accounting, 4(2), 263-276.

Amran, N. A., & Ahmad, A. (2009). Family business, board dynamics and firm value: Evidence from Malaysia. Journal of Financial Reporting and Accounting, 7(1), 53-74.

Amran, N. A., & Ahmad, A. C. (2010). Family succession and firm performance among Malaysian companies. International Journal of Business and Social Science, 1(2), 193-203.

Amrann, N. A., & Ahmad, A. C. (2011). Board mechanisms and Malaysian family companies’ performance. Asian Journal of Accounting and Governance, 2(1), 15-26.

Azizan, S. K., & Ameer, R. (2012). Shareholder activism in family-controlled firms in Malaysia. Managerial Auditing Journal, 27(8), 774 – 794.

Backman, M. (1995). Overseas Chinese business networks in Asia. Sydney: DFAT East Asia Analytical Unit.

Broekhuizen, T. L., Giarratana, M. S., & Torres, A. (2017). Uncertainty avoidance and the exploration-exploitation trade-off. European Journal of Marketing, 51(11/12), 2080-2100.

Carney, M. (1998). A management capacity constraint? Obstacles to the development of the overseas Chinese family business. Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 15(2), 137-162.

Cheong, K. C., Lee, P. P., & Lee, K. H. (2015). The internationalisation of family firms: Case histories of two Chinese overseas family firms. Business History, 57(6), 841-861.

Craig, J., Moores, K., Howorth, C., & Poutziouris, P. (2009). Family business research at a tipping point threshold. Journal of Management and Organization, 15(3), 282-293.

Credit Suisse Research Institue – CSRI. (2017). The CS family 1000 Report. Retrieved from https://www.kreditwesen.de/system/files/content/inserts/2017/the-cs-family-1000.pdf.

Ghee, W. Y., Ibrahim, M. D., & Abdul-Halim, H. (2015). Family business succession planning: Unleashing the key factors of business performance. Asian Academy of Management Journal, 20(2), 103-126.

Goel, S., & Jones, R. J. (2016). Entrepreneurial exploration and exploitation in family business: A systematic review and future directions. Family Business Review, 29(1), 94-120.

Goh, K. S. (2008). Corporate governance practices of Malaysian Chinese family owned business. PhD Thesis, Southern Cross University.

Gohs, C. F., & Rasli, A. (2014). CEO duality, board independence, corporate governance and firm performance in family firms: Evidence from the manufacturing industry in Malaysia. Asian Business & Management, 13(4), 333-357.

Gomez, E. T. (2007). Family firms, transnationalism and generational change: Chinese enterprise in Britain and Malaysia. East Asia, 24(2), 153-172.

Hancıoğlu, Y., Doğan, Ü. B., & Yıldırım, Ş. S. (2014). Relationship between uncertainty avoidance culture, entrepreneurial activity and economic development. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 150, 908-916.

Haniffa, R. M., & Cooke, T. E. (2002). Culture, corporate governance and disclosure in Malaysian corporations. Abacus, 38(3), 317-349.

Ibrahim, H., & Samad, F. A. (2010). Family business in emerging markets: The case of Malaysia. African Journal of Business Management, 4(13), 2586-2595.

Ibrahim, H., & Samad, F. A. (2011). Corporate governance mechanisms and performance of public-listed family-ownership in Malaysia. International Journal of Economics and Finance, 3(1), 105-115.

Jaafar, S. B., Kieran, J., & AbdulWahab, A. E. (2012). Remuneration committee and director remuneration in family-owned companies: Evidence from Malaysia. International Review of Business Research Papers, 8(7), 17-38.

Kraus, S., Harms, R., & Fink, M. (2011). Family firm research: Sketching a research field. International Journal of Entrepreneurship and Innovation Management, 13(1), 32-47.

Liew, Y. C., Alfan, E., & Devi, S. (2015). Family firms, expropriation and firm value: Evidence from related party transactions in Malaysia. The Journal of Developing Areas, 49(5), 139-152.

Mayer, C. J. (2003). What can we learn about the sensitivity of investment to

stock prices with a better measure of Tobin’s Q? School Working Paper, the Wharton School, University of Pennsylvania.

Mokhber, M., Gi, T., Abdul-Rasid, S. Z., Vakilbashi, A., Mohd-Zamil, N., & Woon, S. Y. (2017). Succession planning and family business performance in SMEs. Journal of Management Development, 36(3), 330-347.

Nee, O. H. (2007). An assessment of new management style of chinese family construction related company. Master Thesis, University Sains Islam Malaysia.

Othman, M. N., Ghazali, E., & Cheng, O. C. (2005). Demographics and personal characteristics of urban Malaysian entrepreneurs: An ethnic comparison. International Journal of Entrepreneurship and Innovation Management, 5(5-6), 421-440.

Price Waterhouse Coopers – PWC. (2016). Family business survey 2016: The Malaysian chapter. Retrieved from https://www.pwc.com/my/en/assets/publications/2016-family-business-survey-malaysian-chapter.pdf.

Ramchandran, K. (2012). Indian family businesses: Their survival beyond three generation. Working Paper Series, Indian School of Business, Hyderabad.

Redding, G. (1990). The spirit of Chinese capitalism. Berlin: DeGruyter.

Set, K. (2013). Tourism small and medium enterprises (TSMEs) in Malaysia. International Journal of Business and Social Science, 4(6), 58-66.

Short, J. C., Sharma, P., Lumpkin, G. T., & Pearson, A. W. (2016). Oh, the places we’ll go! Reviewing past, present, and future possibilities in family business research. Family Business Review, 29(1), 11-16.

Sin, G. T. (1987). The management of Chinese small-business enterprises in Malaysia. Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 4(3), 178-186.

Swierczek, F. W., & Ha, T. T. (2003). Entrepreneurial orientation, uncertainty avoidance and firm performance: An analysis of Thai and Vietnamese SMEs. The International Journal of Entrepreneurship and Innovation, 4(1), 46-58.

Ting, S. H. (2017). Language choices of CEOs of Chinese family business in Sarawak, Malaysia. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development, 38(4), 360-371.

To, B. (2010). The adoption of western management methods by Chinese family and publicly listed companies in Asia. Doctoral Dissertation, Middlesex University.

Tsang, E. W. (2001). Internationalizing the family firm: A case study of a Chinese family business. Journal of Small Business Management, 39(1), 88-93.

Ung, L., Rayenda, B., & Chin-Hong, P. (2016). Does retrenchment strategy induce family firm's value? A study from Malaysia. International Journal of Management Practice, 9(4), 394-411.

Wennekers, S., Thurik, R., van Stel, A., & Noorderhaven, N. (2007). Uncertainty avoidance and the rate of business ownership across 21 OECD countries, 1976–2004. Journal of Evolutionary Economics, 17(2), 133–160.

Whah, C. Y. (2007). From tin to Ali Baba's gold: The evolution of Chinese entrepreneurship in Malaysia, IIAS Newsletter, 45, 18, Leiden Unversity repository. Retrieved from https://openaccess.leidenuniv.nl/handle/1887/12815.

Xavier, J. A., & Gomez, E. T. (2018). Ethnic enterprises, class resources and market conditions: Indian owned SMEs in Malaysia. . The Copenhagen Journal of Asian Studies, 35(2), 5-29.

Yeoh, P. L. (2014). Internationalization and performance outcomes of entrepreneurial family SMEs: The role of outside CEOs, technology sourcing, and innovation. Thunderbird International Business Review, 56(1), 77-96.

Yusof, M., Mohd-Nor, L., & Hoopes, J. E. (2014). Virtuous CSR: An Islamic family business in Malaysia. Journal of Family Business Management, 4(2), 133-148.

Zahra, S. A., & Sharma, P. (2004). Family business research: A strategic reflection. Family Business Review, 17(4), 331-346.

Zainol, F. A. (2013). The antecedents and consequences of entrepreneurial orientation in Malay family firms in Malaysia. International Journal of Entrepreneurship and Small Business, 18(1), 103-123.

Zainol, F. A., & Ayadurai, S. (2010). Cultural background and firm performances of indigenous ("Bumiputera") Malay family firms in Malaysia: The role of entrepreneurial orientation as a mediating variable. Journal of Asia Entrepreneurship and Sustainability, 6(1), 3-20.

Zainol, F. A., & Ayadurai, S. (2011). Entrepreneurial orientation and firm performance: The role of personality traits in Malay family firms in Malaysia. International Journal of Business and Social Science, 2(1), 59-71.