The Potential of China’s Bond Market

Wenjing Wang1

Arthur S. Guarino2*

1Zhejiang Business College, Department of Financial Management, Hangzhou, Zhejiang Province, China. |

AbstractThe Chinese bond market is experiencing substantial financial growth. This is evidenced by its opening up to foreign investors who are taking advantage of new investment opportunities in China’s long-term expanding economy. There has been a change in the financial policies of China’s bond market that has permitted more outside funds to come into its market. The influx of investor financial capital into China is a sign of the national government’s drive for economic stimulus. This allows foreign investors to take advantage of the growth of China’s real estate market and the nation’s massive effort to expand and modernize its infrastructure. The Chinese bond market consists mainly of public sector entities rather than private firms. Foreign investors can purchase either bonds issued by state-owned enterprises or by local governments or their financial vehicles. While the Chinese bond market is expanding, there are problems associated with credit ratings that do not correctly reflect data regarding credit quality. This could mean more risk for bond investors than they can tolerate or afford. The Chinese bond market must also compete against bond markets in other parts of the world in regards to returns, interest rates, volatility, safety, liquidity, and marketability. While there is the potential for vast financial opportunities, there is also the possibility of high risk. |

Licensed: JEL Classification |

|

Keywords: |

|

Received: 10 December 2020 |

|

| (* Corresponding Author) |

Funding: This study received no specific financial support. |

Competing Interests: The authors declare that they have no competing interests. |

1. Introduction

China’s bond market has the potential for extraordinary growth in the next ten years. This growth coincides with the expansion of China’s macroeconomy despite the global Covid-19 pandemic now occurring. China’s policymakers are making every effort to see that its macroeconomy will expand in the long and short-term, and they realize that financial capital is vitally important for this expansion. Acquisition of financial capital through the sale of bonds, whether corporate, sovereign, or government, is vital for Chinese companies to expand their operations, hire more workers, seek new global markets, or improve their products and processes through research and development.

China is making an effort to attract foreign capital by allowing foreign investors to purchase Chinese bonds through the China Hong Kong Bond Connect program. Launched in 2017, it is the first time that foreign investors can access the Chinese bond market and it is growing rapidly. In July 2020, foreign investors poured 75.5 billion yuan or U.S.$10.83 billion into China’s bond market via the Bond Connect program (Reuters, 2020). The Chinese bond market, in the long term, has seen exponential financial growth in attracting investment capital in which it climbed from U.S.$4 billion in the 1990’s to approximately U.S.$13.6 trillion today (Andrew, 2020).

Not only does this allow foreign investors to further diversify their investment portfolio, but also seek potentially higher returns and bond yields, as well as spread the risk among different markets. The influx of foreign capital into China’s economy not only helps put money into the nation’s businesses and ventures, but can also assist in balancing pressures the yuan faced after 2015 when the nation experienced an outflow of funds (George, 2020). But taking this a step further, the opening of China’s bond market to foreign investors also means that Chinese policymakers are making a serious effort to modernize and expand its financial capital markets while also increasing the yuan’s presence on the global stage and enhance its usage as a global currency. While this will not be an easy task given China’s past actions, Chinese policymakers are seeking to change past perceptions held by foreign investors and international companies.

However, the Chinese bond market is not without its risks, as with every investment or marketplace. For example, foreign investors are concerned about China’s financial capital controls which could make it extremely difficult for removing funds from the marketplace and the nation if there is a financial or economic crisis, no matter how large or small it may be. Investors, regardless if they are invested in equity or debt instruments, are always concerned about the fastest and most efficient manner to withdraw funds and become liquid in case of an emergency. China must also allow for such investment tools as interest-rate derivatives so that foreign investors may be able to hedge their investments in order to minimize their risk exposures. While Chinese policymakers may not understand how these investment strategies function, they must be amenable to these financial tools and create a derivatives market that foreign investors will need so as to hedge risk. This must also include the use of futures and forward contracts for government bonds, sovereign debt, and corporate debt instruments. In sum, China’s bond market has a seemingly unlimited potential for growth opportunities but must understand the possible risks that every market faces.

2. Overview of China’s Bond Market

Recently, Xie (2020) reported that Chinese government bonds will be included in the FTSE Russell’s flagship World Government Bond Index starting from October 2021. The FTSE Russell is owned by the London Stock Exchange Group. She emphasizes that this decision will result in more than U.S.$100 billion of foreign capital inflow to China. This is because institutional investors must own Chinese government bonds in order to keep their performances tracked in this index with a passive portfolio strategy or beat the average yield. Thomas and Lockett (2020) address the fact that China’s bond market has been liberalized in a deliberate manner over the years. Before the FTSE Russell’s decision, China’s bond market has already been included in the Bloomberg Barclays Index in 2019, along with the JPMorgan Emerging Market Bond Index. They continue to point out that in 2020; foreign investors own 9% of China’s government debts compared to 2% a few year ago. China’s 10-year government debts yield is 2.407%, higher than an equivalent U.S. Treasury bond amid the global Covid-19 pandemic.

After China joined the World Trade Organization (WTO) in 2000, it had been longing for its currency, the Renminbi (RMB) to be an internationally accepted and widely traded currency. Since then, reform and opening up its capital market gradually had been one of the most important strategies towards this goal. The Chinese authorities had been working on the policies and regulations to attract more foreign investors participating in China’s debt market. Guo (2019) indicated that the bond market had been the most open sub-market among all other Chinese financial markets so far. He mentioned that from the year the first panda bond had been issued in 2005, to the end of 2017, ¥123.4 billion of panda bonds had been issued in total in the China Interbank Bond Market (CIBM). Panda bonds were Chinese RMB-denominated bonds from non-Chinese issuers, which were sold in the People’s Republic of China (PRC). He continued to write that 2010 was the year that China’s central bank, the People’s Bank of China (PBOC), permitted foreign central banks, RMB clearing banks, as well as overseas participating banks to trade in China’s interbank bond market with a limited amount of money in Hong Kong and Macao. In 2013, Qualified Foreign Institutional Investors (QFII) and RMB Qualified Foreign Institutional Investors (RQFII) were permitted in trading onshore Chinese bonds under strict rules and regulations. Two years later, in order to meet certain criteria which was required by the International Monetary Fund’s (IMF) Special Drawing Rights (SDR) for major currencies, the PBOC loosened its regulations, for example, simplifying the process in opening trading accounts, lifting quota limits, changing from an approval system to a filing system, as well as enabling various bonds in trading, bond repurchases, bond lending, forwards, and interest rate swaps. In 2016, the PBOC decided to welcome almost all types of foreign institutional investors. China Bond Connect limits were commenced in 2017 by the China Foreign Exchange Trade System (CFETS) and Hong Kong Stock Exchange (HKSE). Its aim is to enable investors from Mainland China and overseas to trade in each other's bond markets through a market infrastructure linkage in Hong Kong. Bond Connect offers Northbound trading and Southbound trading. Northbound trading offers CIBM access to a broader group of international investors, while Southbound trading helps investors from Mainland China to invest in foreign bond markets.

However, Li Xiaojia, the CEO of Hong Kong Exchanges and Clearing Limited, gave a speech in January 2019 in Beijing, pointing out that the Chinese government needed to further loosen policies and regulations for foreign investors in China’s debt market, enabling China’s debts to become a cash equivalent management tool on a companies’ balance sheets. He addressed the need that the total opening up of China’s fixed income market would be the last step towards the RMB’s internationalization. In 2019, Chinese authorities took further actions towards its domestic bond market. First, Xinhua Finance reported that Chinese authorities permitted the first foreign rating company, S&P Global Ratings, to rate its domestic Chinese bonds, and they eventually agreed to allow more overseas rating companies to participate in China’s rating industry. Second, they further improved the relevant rules for the issuance of panda bonds by overseas non-financial enterprises to enhance transparency, marketization, and standardization. Third, they also agreed that the cooperation between Bloomberg and the CFETS to support foreign institutions in investing and operating in the onshore bond market through the internal and external infrastructure. Fourth, Chinese authorities further optimized the market entry system, allowing the grant of Type-A lead underwriting license to foreign institutions, thus facilitating all types of overseas investors to participate in the interbank bond market. The license covered all debt instruments such as medium-term notes, commercial paper, private placement, and asset backed notes. Fifth, they optimized the bond confect’s transaction rules which aimed to improve the price discovery process and transaction efficiency. Sixth, Chinese authorities removed the QFII and RQFII quota restrictions in September. Last, but not least, they promoted China's bond market to be included in the Bloomberg Barclays Global Aggregate Index which was scheduled on April 1st, thus enhancing the international influence of China’s bond market.

Xinhua Finance reported in August 2019 that China’s debt market, which estimated more than U.S.$13 trillion, had surpassed Japan in becoming second in terms of bond market size. Bond Connect limits calculated that so far until September 2020, the average daily trading volume in bond Connect was more than ¥19 billion, approved institutional investors were over 2100, and foreign holdings in CIBM so far was ¥2.8 trillion.

3. Interest Rate and Volatility Rate Comparison in Bonds across Major Global Bond Markets

3.1. Interest Rate Comparison in Bonds across Major Global Bond Markets

Globally, interest rates for bonds will be low, especially for government bonds since most of the world’s economies will be dealing with a recession brought on by the Covid-19 pandemic. Even before the Covid-19 pandemic hit, most nations were starting to see their macroeconomies slow down and this prompted many central banks to lower interest rates in order to spur on their economies. Major central banks, such as the Federal Reserve Bank (the Fed) in the United States, not only lowered their interest rates to near zero percent but also increased their bond purchases in order to put more money into their economies as well as increase liquidity in the bond market. These actions were necessary in order to prevent a possible economic and financial collapse in 2020 and allow some chance of a rebound in 2021. This was a sudden reversal by the Fed since for the past few years it was in the process of raising the Fed funds rate from the situation still resounding from the Financial Crisis of 2008-2009. The reason for this reversal was that the Fed felt that rates had been low for a significant period of time and that an increase was necessary.

Bond interest rates will need to stay low for a protracted time period so that both corporations and governments can borrow at cheaper rates in order to acquire financial capital they desperately need. While it is possible that central banks in Europe and Asia may use negative interest rates to spur on their economies, the possibility of this occurring in the United States is not very likely.

Any rise in interest rates will be slight depending on any improvement in the global macroeconomy. But, based on the rise in the unemployment numbers globally as well as the number of cases of Covid-19 which will affect the macroeconomy of many nations, the chances of increases in bond interest rates does not seem likely. As reported by Allianz Global Investors in the early part of 2020, the annualized returns for government bonds will remain low (Horricher, 2020).

Despite the low interest rates of bonds, the total amount of bonds investors own has gone up. According to the Bloomberg Barclays Global Aggregate Bond Index, the market value of the global bond market has increased by 27 percent since 2018 (Graystone, 2020) . Even with the increase in the number of bonds in the marketplace, the duration for bonds has also gone up. “Over the same two-year period, the duration of the global bond market has increased by roughly 5 percent to a record high, as both corporates and governments have taken advantage of low yields to extend maturities” (Graystone, 2020).

For bond investors, a saving grace with lower interest rates is that the value of their investment will increase. The financial axiom, “When market rates go down, bond prices go up” holds true in the global bond market for 2020 and possibly into 2021. This will keep investors in the bond market for a long time, even as inflation is expected to stay low for the foreseeable future. On the one hand, investors such as pension funds, mutual funds, and insurance companies will have serious problems with diminished interest payments that they will pass on to pensioners, clients, and annuitants. But they will be able to sell their bond holdings at a profit for the next few years if they need to.

In order to avoid the hazard of low interest rates in corporate and government bonds, investors may seek higher interest rates in Asian fixed income instruments. Even on a risk-adjusted basis over a prolonged time period, investors may want to purchase Asian-based bonds due to their higher yields. For example, the total annualized return from December 31st, 2001 to December 31st, 2014 for the J.P. Morgan Asia Credit Index (JACI) fund was 7.6 percent while the Barclays U.S. Aggregate fund for the same time period was 3.5 percent. Also, the total annualized return from December 31st, 2001 to December 31st, 2014 for the HSBC Asian Local Bond Index (ALBI) fund was 6.9 percent while the Barclay’s Global Aggregate fund was 5.6 percent. The volatility for the J.P. Morgan Asia Credit Index (JACI) fund was 7.0 percent while for the HSBC Asian Local Bond Index (ALBI) fund it was 6.5 percent (Matthews Asia).

What will probably be a severe problem for bond investors is that while they seek higher bond interest rates, they take on the higher probability of greater risk. Another financial axiom, “The greater the risk, the greater the potential return”, holds true in this case. As investors seek higher bond interest rates, they must be aware of the increased risk and even volatility. Seeking out these higher rates will help their cash flow situation, but it could mean a greater chance of default on the bonds and therefore wipe out any stream of future income.

3.2. Volatility Rate Comparison in Bonds across Major Global Bond Markets

Bonds could see a higher degree of volatility than they have in the recent past. Two key factors could cause this volatility: the uncertainty of the United States and China in its trade conflicts in the new presidential administration and the continuing uncertainty of the Covid-19 pandemic gripping the globe.

The new presidential administration under Joe Biden faces many economic and financial challenges and the trade conflicts with China ranks high among these. Biden must be able to fashion a trade strategy that will both help the United States with its sagging economy and work with China in the long run. The problem is the damage that was done by the previous Trump administration and its policies and trade agreements, not only with China but the alienating of trade partners in Mexico, Canada, and Europe. Biden must also revive the American economy while battling Covid-19 and avoid shutting down the country or else possibly face economic and financial collapse. These factors could cause major bond markets to experience a high degree of volatility that the Federal Reserve Bank may be powerless to fix.

It has been noted that the global bond market has a lesser degree of volatility than the U.S. bond market due to its size and greater amount of diversification. For investors, this can mean far ranging and wider opportunities for higher returns, as well as a higher amount of volatility and risk. Investors must be prepared for diverse monetary cycles, economic trends, business peaks and troughs, current low inflationary trend, and uncertainty in the area of geopolitics. Investors must also contend with varying returns based upon different nations, markets, and regions. Over a long span of time, the global bond market has provided investors with a higher return with lower volatility as compared to the U.S. bond market (DiMaggio & Ronit, 2020) . An example of this can be seen for the ten years ending on July 31st, 2020 in which the Bloomberg Barclays Global Aggregate Index, which is hedged into U.S. dollars, had posted an average annualized return of 4.17 percent as opposed to a return of 3.88 percent for the Bloomberg Barclays U.S. Aggregate Index while providing 20 percent lesser volatility (DiMaggio & Ronit, 2020). Taking this a step further, in the time period between January 1987 and July 2020, the U.S. bond market as well as the hedged global bond market each averaged extremely low correlations to the Standard and Poor’s 500 Index, at 0.09 and 0.05, respectively. This provides investors with a respectable return and lesser degree of risk.

What could help investors minimize volatility of global bonds is the opportunity to hedge foreign currency. This can be accomplished through the use of currency forwards and futures contracts. This can be done in a cost-effective manner since the currency forward markets are regarded as being the most liquid markets globally so that transaction costs are minimal. For investors, hedging foreign currency back into U.S. dollars helps to lower a fully diversified portfolio’s volatility and increase yield.

The situation with Covid-19 adds a degree of volatility to the bond markets. With the rise of new cases, hospitalizations, and deaths due to the Covid-19 pandemic, global bond markets will see a higher degree of volatility. This will cause yields on investment grade corporate bonds to be artificially high even if they are insured against loss and defaults through the use of derivative instruments. While investors could purchase derivative instruments to act as insurance policies against loss on bonds and minimize their volatility, the cash flow from the bonds could pay for that safety and still have a profit. The strategy would be to go long on the bonds while simultaneously shorting it in the derivatives markets. This would incentivize investors to purchase bonds they normally would not at a higher return and lower risk.

3.3. China’s Bond Market Versus Global Bond Markets

China’s bond market is now starting to open up gradually to the rest of the world. This is necessary if China’s economy is to grow in the coming decades as its leadership is hoping and planning for. China must have foreign domestic investment in the form of foreign capital or else plans for economic and financial growth will take longer than expected by policymakers. China has helped itself by reforming its financial markets such as the Shanghai-Hong Kong and Shenzhen-Hong Kong Stock Connect Programs. China has also been helped by having Chinese equities included in the MSCI Index as well as a small increase of foreign participation in the Chinese stock market in recent times.

While China is making gains in allowing foreign capital to enter, Chinese bond issuers are more focused on the non-government sector which includes state-owned enterprises and numerous government-sponsored vehicles (Eugenio & Maurice, 2018) . Even so, numerous foreign investments of Chinese bonds are mainly in government securities (Eugenio & Maurice, 2018). In order for China to expand its economy and achieve the economic growth it desires, it must liberalize its bond market so that its private sector can acquire more foreign investment capital, improve marketability of bonds, and increase the length of bond maturities. This must come from changes in rules and regulations enforced by China’s governmental bodies.

One of the key changes is that more foreign investors must be allowed to invest in China’s bond market and include diverse parties. Currently, mostly central banks have invested in the Chinese bond market and this accounts for approximately 2 percent of the domestic market (Edmund & Kenneth, 2018) . In Japan, the rate is 9.2 percent while for emerging markets it is 13 percent on average (Zhang, 2016) . Compounding this problem is that the bonds that are purchased are mainly government and policy bank bonds that are favoured by China’s commercial banks (Edmund & Kenneth, 2018). There needs to be diversity among bond issuers and the types of bonds being sold. This can occur if China’s securities rules and regulations are relaxed and allow more foreign investment capital into the marketplace and for corporations to have more flexibility in the types of bonds they can offer.

Global bond markets, such as those in the United States and Europe, have long allowed foreign capital into their borders. They have deemed it necessary so that corporations can have access to more financial capital but also diversify their investor base. While there have been rules and regulations in place to control the possibility of money laundering or tax evasion, the overall objective has been to open the global bond markets to more financial capital so that corporations can expand in the long and short term. China’s bond market is approximately US$16 trillion and ranks as the second largest globally and still needs foreign investment to grow even more (Amanda, 2020).

An enticement for foreign investors to go into the Chinese bond market is the higher returns. While the United States has seen their Treasury note and bond yields decrease, Chinese government bond yields have actually gone up. For example, 10-year Chinese government bond yields are at 3 percent versus a low in April 2020 of 2.4 percent (Alliance, 2020). Given the state of the global economy, this is quite a beneficial return for foreign investors who are trying to avoid markets that have negative yields.

Among the reasons for an increase in China’s bond rates is a stabilizing economy. China has been able to recover at a faster rate from the effects of Covid-19 and their economy is growing in positive territory while other economies around the world will more than likely end up negative. To attract more financial capital, a higher growth rate is probably the best strategy for China’s economy in the long and short term. Higher interest rates for bonds along with opening up of China’s bond market will make them more competitive and attract more foreign investment capital.4. The Future of China’s Bond Market

After valuing China’s bond market, we feel that it has a bright future, however, caution should not be ignored, and hence must be used in making wise investment decisions. In the following, we will list and analyse both the opportunities and risks of China’s bond market at present, as well as in the future.

As substantial money from global sources is flowing rapidly into China’s bond market, we are spurred on to investigate into the rationale behind it, and find fourteen benefits that China’s bond market is offering now and in the future:

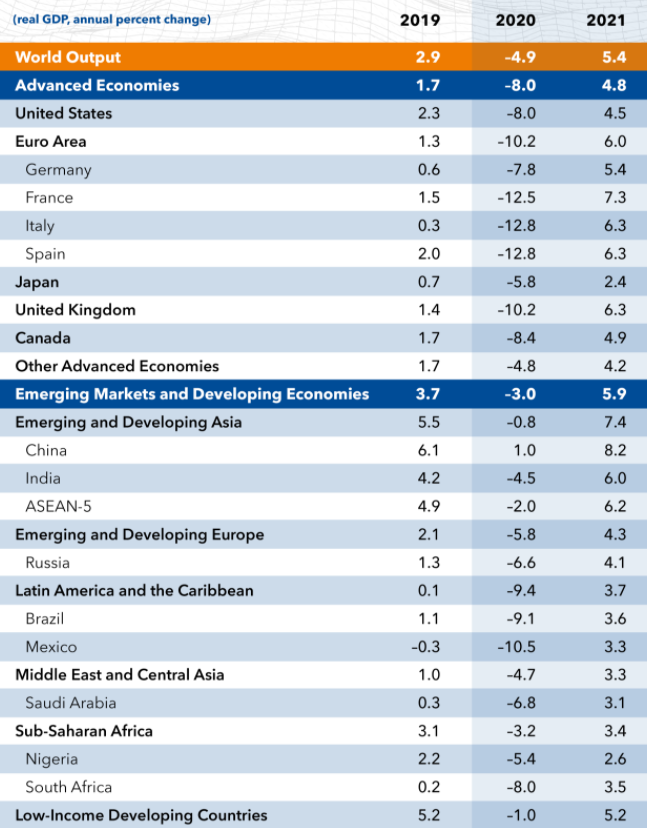

Covid-19 is dragging the economy down of countries across the global in 2020. Almost every country is struggling with unemployment and huge economic loss. Figure 1 is the projection of real GDP growth of all countries around the world. Notably, most of the countries in the world had positive GDP growth rate in 2019, yet in 2020, all of them head in the opposite direction to negative except China. Moreover, China will lead the world with the highest real GDP growth rate in 2021, surpassing all other economic entities. This indicates that China has the capability to handle a sudden public health and global economic crisis and also maintain a high speed of economic growth after the pandemic.

Figure-1. World economic outlook growth projection.

China’s bonds also have higher yields with fairly low risk compared to some other countries mentioned in the third part of this article. Thus, China could be one of the ideal places for investors seeking lower-risk but higher-yield bond markets around the world.

- Improved access for foreign investors after recent reforms. Early in 2016, CIBM Direct Access enabled foreign institutional investors to invest in Chinese onshore market with no quotas. The application procedure only needs the filing of forms and investors must then acquire PBoC acknowledgement in twenty working days, and wait another 6 to 8 weeks until trading is fully permitted. In June 2020, Andrew. (2020) reports that QFII/RQFII schemes have discarded their investment quotas for qualified foreign institutions, allowing them full access to Chinese onshore stock and bond markets. Before, the QFII was limited to a portfolio with 50 percent equity and 50 percent debt. The RQFII has allowed 100 percent debt investment through Chinese currency funds raised by Hong Kong subsidiaries of domestic fund management and securities firms. The end-to-end process of QFII/RQFII from application to actual investing takes nine months, compared to 12 to 18 months in 2016. The restrictions of applying to QFII/RQFII have been weakened starting from 2016. According to James (2020) the Chinese Security Regulatory Committee (CSRC) has implemented a series of reforms to the QFII program, aiming to attract more foreign capital. The CSRC has removed the assets under management criteria and the years of experience needed for application by foreign investors in the QFII program. CSRC has required at least five years of asset management experience and a minimum of US$5 billion of assets under management during the most recent accounting years. Apart from this, it is obligated for those investors to transfer and convert a certain amount of foreign currency to RMB. Furthermore, a much easier linkage between investors overseas and Chinese onshore capital market is Bond Connect which was mentioned above. The qualified investors are like CIBM Direct Access which only allows mid to long term investors rather than short term. The application length for eligible investors takes 10 calendar days. Once approved, the China Foreign Exchange Trading System (CFETS) issues a unique trading license to investors. The Bond Connect attracts many smaller investors by no requests of opening onshore accounts which takes longer time and requires a certain number of restrictions.

- Inclusion of Chinese bonds in global indexes. George (2020) reports that on April 1st, 2019 Chinese government and policy banks’ bonds have been included in Bloomberg Barclays Global Aggregate Index. According to data counted in March 2020, China’s bonds weight is 4.44 percent of this index, and are expected to gain more. JP Morgan Emerging Bond Index (EMBI) has also included Chinese sovereign bonds into its emerging market local index in February 2020. In its EMBI, Chinese sovereign bonds represent 9.38 percent, followed by Mexico as being the number two weighted country in this index. Another recent announcement of conditional inclusion of Chinese government bonds, as mentioned earlier in this article, is the FTSE Russell World Government Bond Index (WGBI). After being rejected several times from the FTSE Russell, China successfully made it in September 2020. The official inclusion will take place in October 2021 if China meets the conditions that WGBI requires. For example, Chinese sovereign bonds must be rated higher than A- by S&P Global. Meanwhile, China needs to actively encourage investors overseas to participate and show a commitment to its own policies.

- Further growth of China’s macro-economy through additional fiscal stimulus is needed in order to boost the economy. In 2020, China has injected the largest ever stimulus package globally in light of the economic disaster caused by the Covid-19 pandemic. According to Tang, Jun, and Sarah (2020) Premier Li Keqiang has confirmed 4 trillion Chinese Yuan (US$559 billion) in a fiscal stimulus package directed to China’s struggling factories and merchants. This stimulus package contains tax cuts, lowering bank interest rates, contribution to social welfare exemption, reducing utility prices, fiscal spending, as well as government bond issuance. China has been trying diligently to secure jobs for its labour force, the livelihood of its citizens, and the market as a whole in order to achieve positive GDP growth in 2020. Also, in this year, Beijing is requiring local governments to spend more in new infrastructure, and allow local governments to issue debt in order to obtain lower interest rate funding. In this way, it helps lower unemployment rates and boost GDP.

- From spot-market auction trading of exchange market-listed bonds to spot-market transactions via one-to-one negotiations, China has committed to optimize its investment environment via the integration of its two existing markets. Zhou and Chen (2020) report that more banking sectors, including foreign banks, are authorized to gain access to spot-market auction trading of exchange market-listed bonds in August 2019, whereby to better merge the interbank and exchange markets. In July 2020, a bigger move towards spot-market transactions via one-to-one negotiations with the issuer available to banking institutions are more welcomed by banks under the current mechanism of market transaction. This shifting not only helps reduce or eliminate spreads which unifies the trading price, but also a sign of continuously optimizing the financial markets for investors.

- As some of the nations’ treasuries were once viewed as safe havens, they are not that safe anymore, as China seems a viable alternative. 2020 has been an extremely volatile year for investors around the globe. With the spread of the coronavirus disease, the world’s economy is tumbling, along with its equities’ prices, the extreme volatility of foreign exchange rates, as well as intensifying political risks. American Treasuries have been regarded as the safest place on the planet for fixed income investors, but not anymore, especially in this year. With the nation’s huge failure in managing Covid-19, Wenjing and Arthur (2020) addressed that the unemployment rate reached a post-World War II historical high in March 2020 with 14.7 percent. Meanwhile, the Deficit Tracker shows that American federal budget deficits are escalating to a post-World War II historical high, also. The total deficit of the United States federal government in October 2020 was $3.1 trillion, almost tripled compared to 2019. The estimated GDP annual growth rate was negative 8 percent in 2020. Last, but not least, the undergoing chaotic and unstable political environment under the current administration brings great uncertainty for what will happen next in the United States. The treasury instruments among European countries are always the second consideration for investors. However, in 2020, most of those countries are suffering severely from Covid-19, with a huge rate of unemployment, as well as an even worse GDP growth rate than the United States. Taking a glance at the world’s third largest economy, Japan, it was favoured by international investors, also, however, its total public deficits have reached 252 percent of its GDP, and its government debt is 10 percent of its GDP. Japan has been the world’s leader in public debt to GDP for the past three decades, and has always been a misleading model for downplaying debt. China, with the second largest GDP in the world, has fairly low government and public deficits, has long been disregarded by international investors because of its tight capital control and the extreme difficult task of entering the onshore financial market. With these years of great effort of aiming to open its capital market and internationalize its currency, China emerges to be the next safe haven for international investors.

- Continuous upgrading of Bond Connect. Bond Connect, as mentioned above, plays an imperative role in connecting China’s Interbank market with both small and large foreign institutional investors. The chief executive of the Hong Kong Monetary Authority addresses the fact that Bond Connect is the main factor that puts Chinese bonds into the inclusion of FTSE Russell World Government Bonds Index. Bond Connect attributes 29 percent of total capital inflow of RMB 1.96 trillion from foreign investors since the launch of the Bond Connect scheme. It also accounts for 52 percent of total turnover in mainland China’s interbank market in the first eight months of 2020. The continuous refinements are made since its start in 2017. Notably, in 2018 delivery-versus-payment settlement, block trading function, and tax exemptions have been implemented. In 2019, the addition of a new electronic trading platform, extension of settlement cut-off time, and increased options for settlement cycle have been implemented. In 2020, special settlement cycle service and extended trading hours introduced new flexibility for investors to engage more than one bank in conducting relevant currency conversion and foreign exchange hedging. Moreover, on October 21st, 2020 Bond Connect launched a new program called ePrime. This program enables bond issuers and underwriters to issue Panda Bonds (U.S. dollar denominated bonds issued by Chinese institutions) and Dim-sum Bonds (RMB denominated bonds issued by Hong Kong entities) through electronic bond issuance system. On the other hand, ePrime also enables investors to obtain electronic access to the prime bond market and complement the existing trading system.

While there are many positive points regarding China’s capital markets, investors must also be aware of the risks involved. Only with a wider and better vision and understanding of the whole Chinese financial market, investors can avoid unnecessary capital loss. The alerts for investors are as follows:

First are China’s capital controls which could make it difficult for investors to withdraw funds in case of a financial or economic crisis. There are possible tighter capital controls by Chinese authorities if the renminbi sees downward pressure. China has a well-known history of capital controlling mechanism towards its RMB outflow. On January 1st, 2018 a new regulation went into effect on the maximum limitation of withdrawing RMB100,000 (approximately US$15,530) annually from mainland China. There is also a cap in every single day’s withdrawing in the amount of RMB10000 (approximately US$1,555). If each individual exceeds this amount of money, their bank account will be frozen for this year and next. Harda (2020) emphasizes that starting in July, Beijing will monitor and record every serial number of each cash transaction over a certain amount of money, in light of the tension with the United States government and downward trending of its currency with U.S. dollars. For example, Zhejiang Province and the city of Shenzhen must report every cash transaction over RMB300,000 and RMB200,000, respectively. Business accounts are required to report if each transaction is over RMB500,000 in these areas. Any suspicious large transactions will be flagged and reported to the central bank. At the beginning of 2020, the Coronavirus outbreak in China made people very anxious about the depreciation of RMB to U.S. dollars, as well as the price drop of equities in mainland China. Moreover, the Sino-American trade war is still ongoing, as well as the severe impact of the Covid-19 pandemic on the global economy, so much so that China is trying even harder to prevent its capital from escaping to overseas markets. Although from May to September of 2020, the RMB to U.S. dollar has experienced substantial appreciation from 7.1316 to 6.8375, that subsequent risks to the exchange rate should be taken into consideration. Thereby, if massive depreciation occurs to the RMB, the Chinese government will surely take further strict actions on its capital controls, and at that time, investors will face difficulties in withdrawing its investment funds.

Second, China does not allow foreign investors to trade government bond futures. Despite recent reforms that Chinese banks are authorized to trade treasury derivatives, it is still in such tight control that foreign investors are not allowed to gain access to government bond futures. In 1990, China started its futures market and expanded quickly until the mid-1990s. During this time period, China’s futures market witnessed massive fraud in trading and strong speculative trading because of loopholes in China’s early regulatory scheme. From then on, China was extremely strict in its futures market control and suspended some of its trading products such as sovereign bond futures. Therefore, this decision of making available for domestic big banks to trade treasury derivatives in 2020 has been considered to be a huge progress in China’s financial market since the mid-1990s. This might be a good underlying sign that there is a possibility in the future that foreign institutional investors may have equal rights to trade Chinese government bond futures, but investors need a substantial amount of patience to wait for the policy to actually be carried out.

Third, the Chinese sovereign bond market is less liquid than U.S. Treasury instruments. China uses its sovereign bonds mostly as pledged bonds rather than trading bonds. In China, most of the pledged bonds in repos and Medium-term Lending Facility (MLF: created for providing medium term monetary policy instruments by PBoC) are Chinese government bonds. Therefore, given this special function, Chinese sovereign bonds are not traded as often as other government bonds such as U.S. Treasury bonds. In 2019, American Treasury bills averaged a daily trading volume of US$130.19 billion, while Chinese government bonds average a daily trading volume of less than US$15 billion.

Fourth, there is the possibility of credit defaults in case of a severe slowdown of China’s macroeconomy. Despite China’s GDP growing at a positive rate amid the Covid-19 pandemic, as well as a good overall outlook for the following year, China is facing problems with most of its micro, small, and medium sized firms. After the rise of Covid-19, many of those companies have been struggling. According to data provided by the Iresearch Consulting Company, nearly 25 percent of micro, small, and medium sized firms have suffered severely due to the coronavirus. This includes 5.8 percent of firms facing bankruptcy, 67 percent of which could not survive with the current cash inflows for three months, and only 15 percent of those companies can survive under the current situation for more than six months. Moreover, there is little government bailout available to help these companies. During the pandemic, Chinese authorities have reduced the bank interest rate in order to help companies struggling with financial problems. However, this kind of policy only significantly benefits large and state-owned companies, leaving aside those micro, small, and medium sized firms. Micro, small, and medium sized firms are usually the least favourable assets on the lists of Chinese banks. It is and has been very hard for those companies to obtain lending from banks. As a result of this, most of the micro, small, and medium sized firms seek much more costly ways to obtain money, such as small lending firms or Peer-to-Peer (P2P) platforms. Some of the recent reforms have made it even more difficult for micro, small, and medium sized firms to survive, such as P2P platforms being banned and under rules of strict control by the government since 2019 in light of many defrauding cases and loopholes found in market regulations. From the consumer’s side, those companies do not benefit from them either. China has long been known for its low per capita income despite the fast pace of its growing GDP. Furthermore, in terms of welfare and coronavirus relief packages, China is not generous to its citizens at all, so sharp retrenchment has occurred amid the pandemic both externally and domestically. Above all, neither domestic nor foreign consumer-driven activities contribute to those firms. China has been in a situation of insufficient domestic demands for decades since it relies heavily on exporting. In 2020, as most countries are suffering from Covid-19 also, the Chinese economy, which is formed mostly by micro, small, and medium sized firms might meet a severe downturn in the future, and large credit defaults are foreseeable to occur at that time.

Fifth, there is liquidity risk in the secondary market for Chinese government bonds which tend to be held to maturity by Chinese banks. Compared to the liquidity of American Treasuries in the secondary market, Chinese government bonds are facing low mobilizing problems. The reasons lie in the four aspects. First, 70-80 percent of Chinese sovereign bonds have a maturity date of 2 to 10 years. This represents that those more frequently tradable central bonds which are with a maturity date of less than 2 years are as a minority. Second, the secondary market for bond trading is still not sophisticated in mainland China in terms of pricing mechanism. Ninety percent of sovereign bonds are held by large banks and financial institutions with depository functions. Because of an inappropriate bond pricing system, most of the government bonds are held until their maturity dates. Third, interest rates in domestic China are fixed rather than floating. Most of its government debt obligation’s interest rates remain stable, hence there are few motivations for bond traders and fund managers to swap interest rates in order to manage their risks. Fourth, the current bond custody system indirectly leads to the fragmentation of the bond market, restricts small and medium investors from entering the inter-bank treasury bond market, and further leads to insufficient liquidity.

Sixth, domestic credit rating agencies (CRAs) are regarded as issuing overly high ratings. Chinese domestic CRAs have long been criticized as being too generous in giving high ratings to bonds and hence failed to provide informative resources to investors. According to Bloomberg’s report in 2020, there are 96 percent AA or above onshore ratings, while in the United States there are only 71.8 percent of debt which are measured as investment grade in 2019. Some of the domestic CRAs are corrupt and provide fake information to its regulators, such as DaGong Credit Rating Company. DaGong has been banned in 2018 from charging high consulting fees to its borrowers and improperly giving high grades to its client. Local CRAs are also late in spotting company defaults, also. For instance, these companies include Company and Kangmei Pharmaceutical Company. Miles, Winne, and Lei (2018) pointed out that local CRAs’ AAA (AA+) rating is equivalent to International CRAs’ A (BBB) rating. They continue to address that Chinese rating scales are very crude and coarse with a notch difference result of 58 basis points in yields, while American and European only have 9-18 basis points. As domestic CRAs still play a vital role in mainland China’s debt market, many investors still rely on their information, the fraud of its rough rating system does not contribute to a healthy and robust bond market, but containing many misleading risks.

Seventh, rising bond defaults and yuan volatility can erode investor confidence in the bond market. Chinese corporate bond defaults in this year have witnessed a sharp increase. In July 2020, Chinese borrowers reneged RMB10.4 billion in bonds, and a similar amount in August also, according to data tracked by Bloomberg. Those companies who have failed or are facing difficulties to pay back their financial obligations that are due are mostly non-state-owned companies. The Chinese government has no rescue plans to back them up, only suggesting that lenders refinance the debt, accept payment delays, or find some other solutions such as swapping bonds for fresh notes with longer maturities. More and more companies have emerged recently to warn publicly that they might be incapable in repaying its creditors, and those companies are mainly airlines, hotels, and real estate developers. Huge amounts of pressure have been placed on debt issuers to raise capital that is set to grow at RMB3.65 trillion (US$529 billion) of bonds with a maturity date by the end of this year. In addition, high volatility in exchange rates of the RMB to the U.S. dollar might be another reason to convince investors to take a second thought when considering entering the Chinese market. China has adopted a much more stable exchange rate between its currency and U.S. dollars, however, recent reform of the globalizing RMB has made Chinese currency float with the international market, thus fluctuations in the RMB are expected and should be taken into consideration when investing in China’s onshore market. Chinese authorities have warned its businesses to watch out for the rising yuan volatility at the end of October. In June, the Chinese yuan has been in its weakest situation against the U.S. dollar since 2008.

5. Suggestions and Predictions

Based on the long-term goal of yuan globalization and the current situation that Chinese financial markets are facing, we strongly recommend that Chinese authorities take the following suggestions and investors consider these ideas as an enhancement of the Chinese capital market.

First, China’s government must ease capital controls so foreign investors can easily withdraw capital in case of a financial or economic crisis. It is always easier to inject capital into China than withdraw from it due to the Chinese government’s fear of large capital outflows over the past decades. This tight capital control contributes significantly on stabilizing the yuan’s exchange rate to U.S. dollars. However, in order to fulfil China’s aggressive goal of reaching 150 percent of American GDP and doubling its per capita income by 2035, the Chinese government has realized it can no longer hold tight to its capital controls, hence attracting more international capital inflows. Over the past few years since 2016 when the Chinese yuan has been added to SDR Basket by the International Monetary Fund (IMF), we have seen efforts that China has made to pave its way towards yuan globalization and capital easing. Nevertheless, these efforts are far from enough for investors to invest in Chinese capital markets without scruple. If a financial or economic crisis occurs to China such as in 2020, we could expect that Chinese authorities would place much tighter controls to its capital outflows again in order to combat its currency fluctuation.

Second, allow investors to trade government bond futures and other derivative instruments. China only permits some of its biggest banks to trade government bond futures as mentioned earlier. This makes Chinese sovereign bonds less attractive to investors despite its relatively high yields than other countries’ government bonds. Bond futures play a vital role in hedging or trading when interest rates fluctuate. It is urgent for the Chinese government to be bolder to open its forward markets and make it possible for more derivative investment tools.

Third, allow for the renminbi to be a free-floating currency. The ultimate goal of yuan globalization requires a pure floating Chinese currency. Therefore, removing or eliminating tight capital controls by the Chinese central government is imperative to meet this ultimate goal. Any sophisticated financial markets request a flexible exchange rate system which is solely based on market forces driven by domestic to foreign currencies, as well as without any government intervention.

Fourth, work to improve liquidity in the Chinese sovereign bond market. Chinese treasuries are low-frequent trading bonds compared to American sovereign bonds due to a large number of them are being held-to-maturity by domestic investors. China has a coarse treasury yield curve interest rate system which does not accurately reflect the yield on securities to their time to maturity on the over-the-counter market. Therefore, government debt investors have little motivation to trade their treasuries frequently and would rather hold them until their due dates. Chinese authorities need to work on managing and strengthening its treasury yield curve in order to improve liquidity in the Chinese sovereign bond market.

Fifth, the Chinese central government should reduce the amount of central government debt and encourage the use of equity as financial capitalization for corporations. By looking at Japan’s eye-catching high national debt, we are informed that the higher the national debt to GDP ratio, the more harmful it affects the macroeconomy, such as high inflation rates and slowing down economic growth. If the Chinese government keeps issuing its central debts without bounds, investors might lose their confidence in future interest paybacks. In the long run, the transmission mechanism within the increasing of government debt decision might lead to economic and social chaos, such as obligation defaults, high tax obligations for its citizens, printing more money to pay for social welfare, losing competitiveness in exporting, as well as a surge in unemployment.

Sixth, set and enforce rules and regulations for domestic credit rating agencies (CRAs). Domestic CRAs are under loose surveillance from Chinese authorities, most of whom conduct rather coarse rating assessments compared to international CRAs. Most of their ratings are one notch higher than the international CRAs. Nevertheless, domestic CRAs ratings play a vital role in mainland China’s bond market due to the easier access to domestic companies than the foreign ones. Unless local CRAs adjust their rating mechanisms closer to the standards that international CRAs use, it is difficult to convince foreign or even local investors to trust them. It has already been a trend that there are some local investors who have conducted their own independent risk assessment research on targeted bonds. The domestic rating company, DaGong Global Credit Rating Company, Ltd was banned from rating for one year in 2018 which signals roughly loose regulations and less serious consequences that CRAs would face after falsely providing information with intentions.

In essence, we still positively believe that China’s bond market can grow exponentially if a proper balance of freedom and control is allowed in the marketplace. With China setting a GDP growth target in 2035, we predict that China will grow to become larger than the U.S. bond market in twenty years. However, if it continues to issue debt without proper bounds, then China’s bond market will probably have a crash at some point in time as part of its growing pains. In essence, it is not a question of if the Chinese bond market will crash but a matter of when. China will welcome small and midsize international investors to participate in the Chinese bond market as part of its ultimate goals of increasing financial market size and yuan globalization.References

Alliance, B. (2020). China’s higher bond yields buck the global trend: Seeking Alpha.

Amanda, L. (2020). China debt: how big is it and who owns it? South China Morning Post.

Andrew, W. (2020). Inside the bond connect: China’s sleeping lion wakes: CITYWIRE.

Andrew., G. (2020). Explainer: Foreign access to China's $16 trillion bond market: Reuters.

DiMaggio, S., & Ronit, W. (2020). Don’t Shun global bonds: AllianceBernstein.

Edmund, G., & Kenneth, A. (2018). China’s bond market: Aberdeen Standard.

Eugenio, C., & Maurice, O. (2018). China’s bond market and global financial markets. IMF Working Paper. WP/18/253.

George, T. (2020). The index inclusion of onshore China bonds: FACTSET.

Graystone, C. (2020). On the markets: Morgan Stanley.

Guo, K. (2019). Chapter 9 opening up China’s bond market: Some considerations: The future of China’s bond market: International Monetary Fund, 438.

Harda, I. (2020). China watches big cash transactions to stem capital flight: NIKKEIAsia.

Horricher, S. (2020). Bond investors should expect continued low yields and low returns. Allianz Global Invetsors.

James, C. (2020). Qualified foreign institutional Investor (QFII): Investopedia.

Jo Harper. (2020). Investment in Chinese Bond Market Grows: The News Lens.

Magdalene, T. (2019). RQFII and QFII: A new chapter begins. BNY Mellon.

Miles, L., Winne, P. H. P., & Lei, Z. (2018). Are Chinese credit ratings relevant? A study of the Chinese bond market and credit rating industry. Science Direct, 87, 216-232.

Reuters, S. (2020). Global investors drive record inflows into Chinese bonds in July. Reuters.

Tang, F., Jun, M., & Sarah, Z. (2020). China pledges largest-ever economic rescue package to save jobs and livelihoods amid coronavirus. The Coronavirus Pandemic.

Thomas, H., & Lockett. (2020). FTSE gives China bonds green light for influential index. Financial Times.

Wenjing, W., & Arthur, G. (2020). The Impact of the Covid-19 crisis on common stock dividend payout policy. Research in Economics and Finance, 5(4), 68-91.

Xie, Y. (2020). China’s bonds win third key index inclusion. The Wall Street Journal.

Zhang, J. (2016). What makes China’s corporate bond market different? : CFA Institute.

Zhou, L., & Chen, J. (2020). China integrates bond market trading. ChinaDaily.com.