Public Debt – Balloon or Anchor? A Macroeconomic Case Study of Canada’s Fiscal and Monetary Policy Response to COVID-19

Keegan Robertson

Ph.D Candidate, School of Economics, Finance and Property, Curtin University, Australia. |

AbstractNew perspectives have emerged during the COVID-19 era on a longstanding dilemma regarding the best path to managing public debt. Two main schools of thought are evident in available literature: those that believe that a government must maintain fiscal responsibility by eventually reducing its debt levels through austerity measures; and those that believe, based on newer progressive economic theory, that large public debt is not only acceptable, but that government debt is crucial to a productive society. This article explores the case of Canada by reviewing the measures enacted in an attempt to mitigate the shock to the economy, and exploring the potential pros and cons of the two distinct policy options. It is proposed in this article, that the tenets of Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) should be considered as an innovative approach to ensuring appropriate use of available resources. |

Licensed: |

|

Keywords: JEL Classification: |

|

Received: 17 March 2021 |

Funding: This study received no specific financial support. |

Competing Interests: The author declares that there are no conflicts of interests regarding the publication of this paper. |

1. Executive Summary

In Canada, initial measures to prevent the spread of COVID-19 have had substantial economic impact, and the government responded with one of the largest fiscal stimulus packages in the world, totalling at least CAD $354 Billion or 16.4% of GDP (a figure that has likely increased since publication) (IMF, 2020a). What this means in terms of total change to public debt in Canada is unclear as various reports provide widely ranging figures, which are explored further in this paper. A dilemma has been reinvigorated concerning the best path to managing public debt, and two main schools of thought are evident in available literature: those that believe that a government must maintain fiscal responsibility by eventually reducing its debt levels through austerity measures; and those that believe, based on newer progressive economic theory, that large public debt not only acceptable, but that government debt is crucial to a productive society (Pigeon, 2020). Focus on enacting austerity measures to eventually reduce government debt reduces the risk that it will become unmanageable and lead to default which could seriously hamper future growth; however, this approach is criticised for making poor use of the available resources that a government can command, and leads to potentially unnecessary periods of economic retraction that serves to widen disparity (Mitchell, 2020). Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) suggests that governments should solely focusing on the real availability of labour and resources and that, in their view, the imaginary barrier of how projects will be financed should be debunked, permitting spending of whatever is necessary to engage currently idle resources to create prosperity overall (Connors & Mitchell, 2017). This theory has been criticised as being unrealistic, based in politically-charged ideology, and would lead to hyperinflation and a gross intergenerational transfer of responsibility (Mankiw, 2020). This report concludes that Canada should consider re-framing its relationship with public debt using the guiding strategies presented in MMT. Governments should use all available methods to engage idle resources, which is particularly relevant in the context of COVID-19 where large sectors of the population remain unemployed, and based on the persistence and recurrence of COVID-19 cases without a vaccine, current economy-building plans, based on traditional economic theories and modelled on past stimulus interventions, are quickly becoming a decreasingly viable solution (Government of Canada, 2020b; Mitchell, 2020).

2. Introduction

The COVID-19 global pandemic may become one of the most defining events in recent world history, and its impacts continue to dominate the global political, social, and economic landscape. According to Welfens (2020) two of the main economic challenges in a pandemic are “how to minimise transmission … [and] how to fight negative macroeconomic effects.” In response to the first challenge, social distancing measures are the only known, effective method to reduce transmission (Comfort, Kapucu, Ko, Menoni, & Siciliano, 2020). To the second point, ethics are inextricably linked to decision-making when considering purely economic impacts against social welfare in the COVID-19 response (Maffettone & Oldani, 2020). Some governments such as those in the UK and Sweden had initially elected to limit policy interventions that would impact economic activity under the so-called ‘herd-immunity’ approach, while other governments such as France and Germany issued statements that economic cost would not be a consideration in health policy responses (Maffettone & Oldani, 2020). While it is clear that government policy has serious consequences for economic activity (Maffettone & Oldani, 2020), the economic impact of health policy has not reached consensus. Some researchers conclude that early lockdown not only saved lives but that the ‘lives versus livelihood’ trade-off is a myth; the short term costs are outweighed by future economic benefits of strong public health (Balmford, Annan, Hargreaves, Altoè, & Bateman, 2020; IMF, 2020b). There has been limited research on this subject in relation to COVID-19 thus far, and historical research is inconclusive; simply put, researchers disagree (IMF, 2020b). What seems to have been conclusively agreed is that where countries implement lockdown, there are negative impacts to GDP, consumption, investment, production, sales, and employment (IMF, 2020b). Governments and central banks around the world, and particularly in Canada, have responded with a range of macroeconomic measures to help mitigate these effects of these policies, without which economic downturn would be substantially worse (Brodeur, Gray, Islam, & Jabeen, 2020; IMF, 2020b). This paper explores Canada’s fiscal and monetary policy responses to COVID-19, and examines the dilemma between choosing to continue measures that increase public debt, and the introduction of austerity measures in order to balance the budget. In weighing the pros and cons of either option, it is concluded that continuing to increase public debt does not pose as substantial of a risk as some may believe, and a coordinated global approach to accepting increasing ratios of public debt to GDP should be pursued.

3. Background

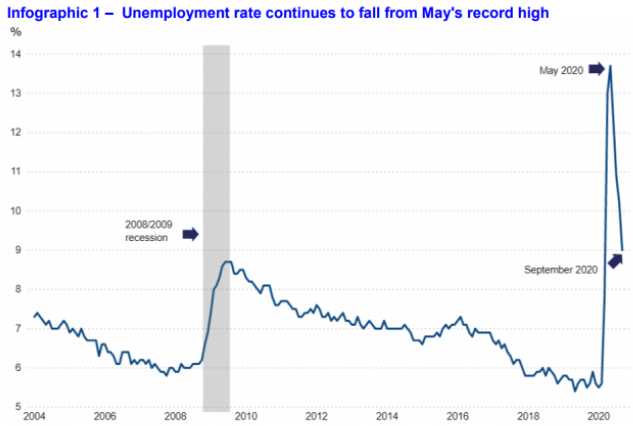

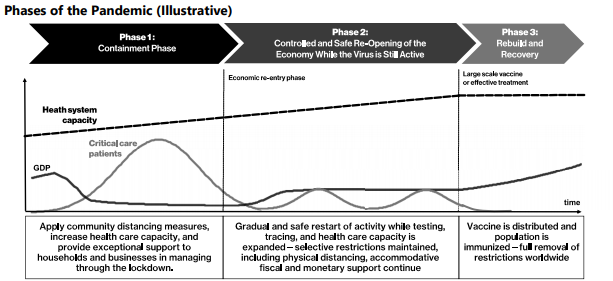

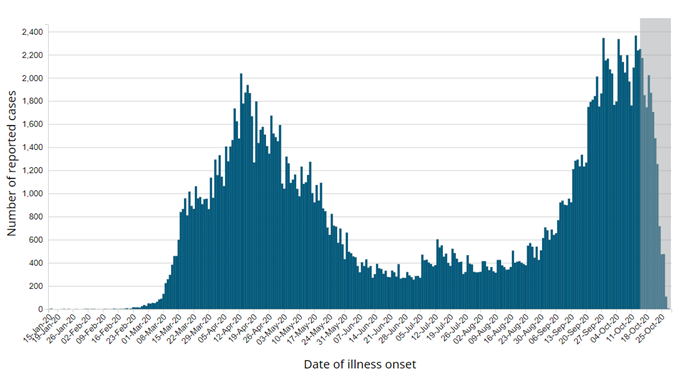

Canada is a country of 38 million people, and as of October, 2020, there have been approximately 200,000 recorded cases of COVID-19, and 10,000 resulting deaths (Government of Canada, 2020a). Roughly 3.7 million people have used the Canada Emergency Wage Subsidy program, estimated to cost CAD $68.5 billion which makes up only a portion of the overall CAD $354 billion stimulus package the Canadian government has implemented (DOFC, 2020b; IMF, 2020a). Other fiscal and monetary measures include lowering the interest rate to 0.25%, debt repayment deferrals, and additional grants, services, and funding programs targeted at marginalised or disproportionately impacted groups; total direct fiscal support is in excess of 10% of GDP, the highest among G7 countries (DOFC, 2020a; Government of Canada, 2020c). The government fiscal and monetary policy has mirrored the response to the 2008 Global Financial Crisis – cutting interest rates, and spending to increase demand and production (Muhammad, 2020). While employment recouped roughly half of the losses compared with pre-COVID levels by September, illustrated in Figure 1 (Statistics Canada, 2020), and economic outlooks published by the government were promising, a resurgence of cases in October is already reaching higher levels than ever before, shown in Figure 3 (Government of Canada, 2020b), which is throwing projections into disarray since the government acknowledges its modelling assumed no substantial second wave of the pandemic would occur in Canada, demonstrated in Figure 2 (Bank of Canada, 2020; DOFC, 2020a).

When considering what these fiscal and monetary actions mean to public debt figures, the Canadian government says that 2020 net debt remains under 50% of GDP, and despite spending measures will remain low relative to other countries (DOFC, 2020a). Methods of reporting debt have been found to be comparably unreliable and seem to be used for political purposes depending on the conclusion the author wishes the reader to reach (Seiferling, 2020). A credit ratings report critical of growing government debt indicates Canada’s consolidated gross government debt in 2020 is 88.3% of GDP, and forecasts debt up to 131.5% of GDP by 2022 (Canada’s Spending Pledges to Push Federal Deficit Higher Still, 2020). One potential difference in reporting is that Canada’s gross subnational debt to GDP is the highest in the world, at over 40% of GDP in 2019 (Hanniman, 2020). This is a substantial consideration and the Bank of Canada has committed to buying 40% of short term provincial debt, which provides liquidity, but does not resolve long term issues (Hanniman, 2020).

Source(s): Labour force survey, table 14-10-0287-01.

Figure-2. Canadian government projected phases of COVID-19 and GDP growth. Reproduced from DOFC (2020a).

Figure-3. Cases of COVID-19 in Canada by date of illness onset. Reproduced from Government of Canada (2020c).

There is a real risk of provincial default due to strong regional independence sentiments, which could damage national interests (this happened in 1936 when Alberta refused federal supervision as a condition of bailout) (Hanniman, 2020). If the federal government does assume provincial debts, this could dramatically change the story being told about escalating Canadian debt figures. In addition to domestic concerns, there is also global pressure for more affluent countries to support developing countries in their fight against COVID-19 related strains (McKibbin & Fernando, 2020; Stubbs, Kring, Laskaridis, Kentikelenis, & Gallagher, 2021).

Politically, there are also risks to Canadian stability, particularly as it relates to the question of debt. If the minority government cannot garner support from the New Democratic Party for its September ‘From the Throne Speech’ at reopening of parliament, it may trigger early elections (Canada’s Spending Pledges to Push Federal Deficit Higher Still, 2020). The government will be pressured to balance the budget, and while it has not announced any new revenue raising measures such as increased corporate or wealth taxes (which are opposed by influential groups), the only other option would be to reduce spending which would lead to increases in unemployment and economic retraction (Canada’s Spending Pledges to Push Federal Deficit Higher Still, 2020; Hanniman, 2020; McDonald, 2020).

4. Policy Dilemma

Debate among economists and politicians about the best way to manage public debt in relation to the pandemic is becoming increasingly divisive, and commentators can be allocated into two broad camps: those that support traditional mainstream economic theories, which indicate that budgets must eventually be balanced through ‘responsible’ austerity measures (though they may disagree on when or how that action should be taken); and those that support progressive, more experimental economic theories centred around Modern Monetary Theory (MMT), which indicates that large public debt is not problematic, and that governments generally should not be concerned with trying to actively reduce public debt (Kelton, 2020).

5. Cost-Benefit Analysis

Option 1: Austerity measures based on traditional economic theories

Canada is spending hundreds of billions of dollars on its stimulus package (DOFC, 2020a). Economists indicate that supporting near term growth may lead to amassing debt which could become unmanageable in the future, and puts undue pressure on future generations to pay for the current generation to maintain its status quo (Cross, 2020; DOFC, 2020a; IMF, 2020b; Maffettone & Oldani, 2020). By implementing fiscal austerity measures, which could include a combination of increased revenue generation through taxation on those that can afford it, and reduction in spending, the ‘looming debt crisis’ can be progressively managed through control and responsibility (IMF, 2020b; Maffettone & Oldani, 2020; Oliver, 2020). Increased expenditure to stimulate demand and output has been deemed unlikely to be successful when the virus continues to spread, since measures are designed in a way that means many cannot work, and spending works better when social distancing measures are not in place (Maffettone & Oldani, 2020).

On the contrary side, increased revenue through taxation has been opposed by influential groups, and without multinational coordinated responses to corporate tax changes, businesses can continue to dodge obligations in seeking substitute havens (Hanniman, 2020; Stiglitz, 2019). The alternative austerity measure, decreased spending, would cause unemployment to rise, GDP retraction, and unequal impacts on the poor and marginalised (DOFC, 2020a; Maffettone & Oldani, 2020; McDonald, 2020). Traditional fiscal approaches have already been burdening youth with poor job entry prospects, a significant climate crisis, and unattainable housing prices (Cross, 2020).

Option 2: Permitting public debt to rise based on Modern Monetary Theory

The COVID-19 pandemic has brought Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) into the central economic debate (Rose, 2020). MMT advocates for currency-issuing governments to take advantage of idle resources by printing the necessary money, and to focus on undertaking projects that would produce substantial net public benefit rather than being concerned with public debt figures (Dillow, 2020; Kravchuk, 2020; Mitchell, 2020; Rose, 2020). Proponents argue that debt is only one side of the balance sheet, and the net outcomes in growth and opportunity will outweigh the increases to debt, as the rate of interest on debt is less than GDP growth, and has historically been so, meaning there is no financial cost to holding debt and debt as a share of the economy will shrink over time without any need for surplus (Dillow, 2020; Kravchuk, 2020). The only limiting factor to growth is the availability of real material and labour (Kravchuk, 2020). Also on this basis, any argument about the generational transfer of debt responsibility is less factual when considering the productive investments the debt funds, of which the future generations will benefit proportionally more (Connors & Mitchell, 2017).

This approach would also require a substantial effort to reframe public understanding of government finance, as financial language has been used by conservative political commentators and economists to reinforce myths linking government and household budgets, which is a fallacy as demonstrated in Table 1 (Connors & Mitchell, 2017; Kelton, 2020; Kravchuk, 2020; Mitchell, 2020).

| Focus of attack | Metaphorical Claim | Implied Meaning |

| Government spending | The country is living beyond its means | Excess spending requires sacrifice Cuts needed immediately |

| Country has maxed out its credit card |

Run out of money due to irresponsible spending | |

| Spending like a drunken sailor | Wanton irresponsibility and delinquent behavior | |

| Fiscal balance | Budget black hole | Budget beyond human control like the collapse of a massive star |

| Deteriorating state of the budget | Budget is like a body and is in state of ill-health requiring emergency surgery—there is no alternative | |

| Mushrooming budget deficit | Budget is an organic entity and is out of control | |

| The country has run out of money, it is broke | Government budget is like a household budget—the economy is like us | |

| Public debt | The country is bankrupt | Country is a badly managed insolvent firm |

| The public debt mountain | Debt is dangerous and insurmountable | |

| Burdening our grandchildren | Debt threatens fundamental unit of society and undermines future prosperity | |

| Mortgaging the future | Current government debt compromises future spending | |

| Income support | Welfare dependency | Welfare net is like a drug for the populace, encouraging ill-health and addiction |

| Dole Bludgers, Skivers | Unemployed are lazy and undeserving |

A government must spend its currency in order to tax (Pigeon, 2020). Taxes can serve to reduce private purchasing power, or redirect consumption habits for ideological reasons, but none of taxation’s purposes relate to funding government spending (Connors & Mitchell, 2017). This accounting actuality exposes a crucial flaw in the perception of deficit, which implies something negative, and surplus, which implies something positive (Connors & Mitchell, 2017). The reality, according to MMT theorists, is that government deficit is the sole source of net financial assets in the private sector; if the private sector wants to save, the government must be in deficit (Connors & Mitchell, 2017). The opposite scenario – a fiscal surplus – while linguistically positive, does not result in ‘public savings’ but destroys private wealth by forcing liquidity which is deflationary (Connors & Mitchell, 2017).

A country to which MMT supporters point as a shining example, is Japan, which has a public debt above 240% of GDP, the highest in the world (Daley et al., 2020). Despite this, risk premiums on Japan’s borrowing remain low (Daley et al., 2020) and while US GDP growth is higher, Japan ranks better in numerous desirable categories of social welfare, “including life expectancy, infant mortality, working class incomes, and cost of basic necessities … [and] inequality” (Mahbubani, 2020).

According to Rose, aversion and criticism of MMT can be reduced, ultimately, to fear of inflation (2020). Some economists suggest that printing money increases reserves, on which the government pays interest; if it pays for that interest by continually printing money aggregate demand increases, inciting inflation (Mankiw, 2020; Rose, 2020).

To Rose’s point, one may also add that much of the criticism is founded in conservative political ideology, and attacks are made on the origin and supporters of the theory which according to Mankiw, “was developed in a small corner of academia and became famous only when some high-profile politicians—particularly Senator Bernie Sanders and Representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez—drew attention to it because its tenets conformed to their policy views” (2020, 1). There is also fear of growth of the size of government which ideologically is not supported by political conservatives (Cross, 2020). They argue that MMT’s approach will crowd out private sector investment and reduce output and consumption (Coates, 2020; Daley et al., 2020).6. Conclusion and Recommendations

In consideration of the presented information about the potential benefits and drawbacks of pursuing fiscal austerity versus continuing to allow the growth of public debt, this report finds that Canada should consider adjusting its strategy to align with the principles of MMT. The traditional approaches to fiscal and monetary policy have been contributing to a growing divergence in equality, lack of action on critical issues of public concern including climate change, and erosion of sovereign power in the face of supranational corporate consolidation of authority (Mitchell, 2020; Stiglitz, 2019). These items suggest that continuing to pursue the current course will result in significant further damage to the wellbeing of younger generations, which was also a critical consideration raised by those who support mainstream solutions (Cross, 2020). These growing issues could be comprehensively addressed by re-framing the relationship between government and debt, which would no longer act as a constricting factor on public activity. Where an ideologically desirable outcome can feasibly be achieved with available real resources it should be done, financing aside (Kravchuk, 2020). The government should take active steps to educate the public about the realities that underpin public finance as contrasted with household budgets, in order to build popular support for a progressive approach (Connors & Mitchell, 2017). Compliance, acceptance, and support for government initiatives is critical to their success, and trust has been shown to be based on perceived effectiveness, particularly in the ability to contain the effects and spread of COVID-19 (Brodeur, Gray, Islam, & Jabeen Bhulyan, n.d; Lazarus et al., 2020; Maffettone & Oldani, 2020). The government should also seek to establish multilateral links with other world governments to build similar methodology amongst its contemporaries, a type of cooperation that has been eroding in recent years (Comfort et al., 2020; Trichet, 2020; Welfens, 2020). By establishing a coordinated approach to re-envisioning public fiscal and monetary policy, the individual risks to Canada could also be reduced by maintaining its relative global economic position (DOFC, 2020a; Smith, 2020).References

Balmford, B., Annan, J. D., Hargreaves, J. C., Altoè, M., & Bateman, I. J. (2020). Cross-country comparisons of Covid-19: Policy, politics and the price of life. Environmental and Resource Economics, 76, 525–551. Available at: 10.1007/s10640-020-00466-5.

Bank of Canada. (2020). Monetary policy report – July 2020. Ottawa, Canada: BOC.

Brodeur, A., Gray, D., Islam, A., & Jabeen Bhulyan, S. (n.d). A literature review of the economics of COVID-19. Journal of Economic Surveys.

Brodeur, A., Gray, D., Islam, A., & Jabeen, B. S. (2020). A literature review of the economics of COVID-19 (IZA DP No. 13411). IZA Institute of Labour Economics. Retrieved from: https://www.iza.org/publications/dp/13411/a-literature-review-of-the-economics-of-covid-19 .

Canada’s Spending Pledges to Push Federal Deficit Higher Still. (2020). Fitch wire. Retrieved from: https://www.fitchratings.com/research/sovereigns/canadas-spending-pledges-to-push-federal-deficit-higher-still-25-09-2020 .

Coates, W. (2020). Modern monetary theory: A critique. CATO Journal, 39(3), 563-576.

Comfort, L. K., Kapucu, N., Ko, K., Menoni, S., & Siciliano, M. (2020). Crisis decision‐making on a global scale: Transition from cognition to collective action under Threat of COVID-19. Public Administration Review, 80, 616-622. Available at: 10.1111/puar.13252.

Connors, L., & Mitchell, W. (2017). Framing modern monetary theory. Journal of Post Keynesian Economics, 40(2), 239-259. Available at: 10.1080/01603477.2016.1262746.

Cross, P. (2020). Start thinking about the post-COVID economic recovery now. In Getting on the road to a post-COVID economic recovery: principles for a return to work and prosperity (pp. 7-10). Ottawa, Canada: MacDonald-Laurier Institute.

Daley, J., Wood, D., Coates, B., Duckett, S., Sonnemann, J., Terrill, M., & Wood, T. (2020). The Recovery Book: What Australian governments should do now. Retrieved from: https://grattan.edu.au/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/Grattan-Institute-Recovery-Book.pdf.

Dillow, C. (2020). Record borrowing – no problem. Investors Chronicle. Retrieved from: https://www.investorschronicle.co.uk/chris-dillow/2020/08/13/record-borrowing-no-problem/ .

DOFC. (2020a). Economic and fiscal snapshot 2020. (Cat No.: F2-277/2020E-PDF). Ottawa, Canada: DOFC.

DOFC. (2020b). Extending the Canada emergency wage subsidy. Ottawa, Canada: DOFC.

Government of Canada. (2020a). Canada’s COVID-19 economic response plan. Retrieved from: https://www.canada.ca/en/department-finance/economic-response-plan.html . [Accessed October 16, 2020].

Government of Canada. (2020b). Coronavirus disease (COVID-19). Retrieved from: https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/diseases/coronavirus-disease-covid-19.html . [Accessed October 16, 2020].

Government of Canada. (2020c). Coronavirus diseases (COVID-19): Epidemiology update. Retrieved from: https://health-infobase.canada.ca/covid-19/epidemiological-summary-covid-19-cases.html. [Accessed October 28, 2020].

Hanniman, K. (2020). COVID-19, Fiscal federalism and provincial debt: Have we reached a critical juncture? Canadian Journal of Political Science, 53(2), 279-285. Available at: 10.1017/S0008423920000621.

IMF. (2020a). Policy responses to COVID-19. Retrieved from: https://www.imf.org/en/Topics/imf-and-covid19/Policy-Responses-to-COVID-19#C . [Accessed October 16, 2020].

IMF. (2020b). World economic outlook: A long and difficult ascent. Washington, DC: IMF.

Kelton, S. (2020). Should governments run COVID-related deficits?; Deficits can help aid the recovery. National Post. Retrieved from: https://www.proquest.com .

Kravchuk, R. S. (2020). Post-keynesian public budgeting & finance: Assessing contributions from modern monetary theory. Public Budgeting & Finance, 40(3), 95-123. Available at: 10.1111/pbaf.12268.

Lazarus, J. V., Ratzan, S., Palayew, A., Billari, F. C., Binagwaho, A., Kimball, S., & El-Mohandes, A. (2020). COVID-SCORE: A global survey to assess public perceptions of government responses to COVID-19 (COVID-SCORE-10). PloS One, 15(10), e0240011. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0240011.

Maffettone, P., & Oldani, C. (2020). COVID-19: A make or break moment for global policy making. Global Policy, 11(4), 501-507. Available at: 10.1111/1758-5899.12860.

Mahbubani, K. (2020). What Japan “disease”? International Economy, 34(2), 16-40.

Mankiw, N. G. (2020). A skeptic's guide to modern monetary theory (NBER Working Paper No. 26650). National Bureau of Economic Research.

McDonald, I. M. (2020). Macroeconomic policy to aid recovery after social distancing for COVID-19. The Australian Economic Review, 53(3), 415-328. Available at: 10.1111/1467-8462.12387.

McKibbin, W., & Fernando, R. (2020). Global macroeconomic scenarios of the COVID-19 pandemic. Centre for Applied Macroeconomic Analysis, Working Paper No 62/2020.

Mitchell, B. (2020). A cause for celebration: A paradigm shift in macroeconomics is underway. Australian Quarterly, 91(4), 18-29.

Muhammad, M. R. (2020). International financial credit crises; Lessons from Canada. Journal of Economics Bibliography, 7(2), 100-110. Available at: 10.1453/jeb.v7i2.2070.

Oliver, J. (2020). Austerity straw man can't hide PM's plan for fiscal ruin. National Post. Retrieved from: https://www.proquest.com .

Pigeon, M.-A. (2020). Rethinking the perceived perils of sovereign government debt. Johnson Shoyama Graduate School of Public Policy. Retrieved from; https://www.schoolofpublicpolicy.sk.ca/research/publications/policy-brief/covid-series-rethinking-the-perceived-perils-of-sovereign-government-debt.php .

Rose, J. (2020). Pipe dream or quick fix? On the post-Covid allure of modern monetary theory. The Spinoff. Retrieved from: https://thespinoff.co.nz/business/12-07-2020/a-case-for-modern-monetary-theory-and-guaranteed-jobs-for-all/.

Seiferling, M. (2020). Apples, oranges and lemons: Public sector debt statistics in the 21st century. Financial Innovation, 6(37), 1-17. Available at: 10.1186/s40854-020-00193-2.

Smith, F. (2020). Analysis: For Canada, keeping triple-A rating may not be the focus it once was. Reuters. Retrieved from: https://www.reuters.com/article/us-canada-economy-ratings-analysis-idUSKBN2711DN .

Statistics Canada. (2020). Labour force survey, September 2020. Ottawa, Canada: Statscan.

Stiglitz, J. (2019). Corporate tax avoidance: It's no longer enough to take half measures. The Guardian. Retrieved from: https://www.theguardian.com/business/2019/oct/07/corporate-tax-avoidance-climate-crisis-inequality .

Stubbs, T., Kring, W., Laskaridis, C., Kentikelenis, A., & Gallagher, K. (2021). Whatever it takes? The global financial safety net, Covid-19, and developing countries. World Development, 137, 1-8. Available at: 10.1016/j.worlddev.2020.105171.

Trichet, J.-C. (2020). Sound macro policies are the best vaccine against future instability. International Economy, 34(2), 16-40.

Welfens, P. J. J. (2020). Macroeconomic and health care aspects of the coronavirus epidemic: EU, US and global perspectives. International Economics and Economic Policy, 17, 295-362. Available at: 10.1007/s10368-020-00465-3.