The Impact of Economic Crises on the Performance of Non-Financial Corporations in the Czech Republic

Stanislava Hronova1*

Richard Hindls2

1Department of Economic Statistics, Faculty of Informatics and Statistics, Prague University of Economics and Business, Czech Republic. |

AbstractSince the 1990s, the Czech economy has faced four crises. Each of them had different causes, duration and consequences for the non-financial corporate sector. The first crisis (1997-1998) had internal causes and severely affected non-financial firms. In contrast, the second crisis (2009) had external economic causes and non-financial corporations emerged with a positive economic outcome. As a result of extremely rigorous economic policies and net borrowing by non- financial firms, the Czech economy experienced a crisis in 2012 and 2013. The COVID- 19 pandemic was the external, not economic cause of the fourth crisis (2020-2021) that brought about a successful outcome for non-financial corporations. The aim of this analysis is to answer the question of what causes these divergent economic results and why the external impulses of the crisis led to a reversal of the traditionally negative economic balance. The results showed that the levels of indebtedness and profitability conceal the main differences in conditions. The analysis is based on data from the Czech National Accounts and uses relative indicators to describe the economic behaviour of non-financial corporations constructed in such a way that their explanatory power is closer to the conditions for assessing economic performance in corporate practice. |

Licensed: |

|

Keywords: JEL Classification |

|

Received: 17 June 2022 |

Funding: This research is supported by Faculty of Informatics and Statistics, Prague University of Economics and Business (Grant number: IP400040). |

Competing Interests: The authors declare that they have no competing interests. |

1. Introduction

In term of the development of the Czech economy the period from 2000-2006 can be considered quite successful. The period 2001-2004 was characterised by stable economic growth (higher than the average of the European Union countries) supported by high growth rates in industrial and construction production, growth of household and government consumption with gradual improvement of foreign trade relations including exchange rates, strengthening of the Czech Crown, a stable or moderately decreasing unemployment rate and decreasing prices charged by industrial producers. The growing deficit of the state budget, the doubling of the general government debt, the growth of the general government deficit towards the end of the period, the increase in foreign indebtedness as related to GDP must be mentioned when discussing the negative aspects of developments. In 2005-2006, the nature of the growth changed; foreign trade became the main factor in economic growth, the Czech Crown continued to strengthen, the level of government debt was stabilised, the government deficit decreased and the unemployment rate decline. On the other hand, however, the imbalance in the current account of the balance of payments was widening, external indebtedness increasing, consumption was rising and consequently, household indebtedness was also rising. However, the global financial crisis that began in 2008-2009 and the subsequent recession in 2012-20131 put an end to this development phase of Czech economy.

The influence of global crisis or external factors led to the decline in GDP in 2009 which was accompanied by a high government deficit and a rapid increase in government debt. Economic policies that take place in the Czech Republic were restrictive resulted in a decline in public investments and economic activity as well as the 2012-2013 recession of the Czech economy. The year 2014 marked a return to subsistence with low inflation, low unemployment, reasonable wage growth and gradually declining general government debt. However, the COVID -19 pandemic in 2020 presented unpredictable problems which resulted in decline in GDP and a rise in government debt not in just in Czech Republic but also globally. Government restrictions to combat the pandemic (closure of shops, restaurants, hotels and other services), coupled with household concerns, caused a drastic reduction in household consumption.2

The causes, evolution and impact of economic crises are never the same and this is also true in the case of the Czech Republic. In spite of such differences, it turns out that in the Czech Republic, in the years of the externally induced crises (2009, 2012 and 2020), when GDP decline and the deficit and debt of the government grew, the performance of the non-financial corporations ended in surplus.3 What made these crises distinct from one another in perspective of the non- financial corporate sector’s performance? How has the economic behaviour of Czech non-financial corporations changed over the last 30 years?

The aim of this article is to answer the question of what was the cause of different economic results of Czech non-financial corporations in the different periods of four crises that the Czech economy has undergone over the past 30 years, especially why did external impulses of the crisis lead to a reversal of their traditionally negative balance.

We would like to answer this question by analysing data for the Czech non-financial corporation sector from 1995 to 2020. The analysis is based on data from the Czech National Accounts and uses relative indicators specific to describe the economic behaviour of non-financial corporations, constructed in such a way that their explanatory power is closer to the conditions for assessing economic performance in corporate practice. Our source is publicly available data from the Czech Statistical Office.

2. A Theoretical Approach to the Analysis of Non-Financial Corporations

Various analyses have been conducted on the economic behaviour of non-financial corporations using a general framework of sector analyses, primarily obtained from the national accounts data. They are mostly regular reports of statistical offices or central banks, standardised in their structure and contents – for example, Eurostat (2021) provides an analysis of financial assets and liabilities of non-financial corporations across European Union (EU) and Euro-Area (EA-19) as well as for individual EU Member States. Eurostat (2022) focuses on investment and the distribution of profit for non-financial corporations in the EU and the EA-19. The analysis is based on national accounts data from 2010-2020. An example of a very detailed "national" sectoral analysis of non-financial corporations based on national accounts data is undoubtedly Banco (2016) . In addition, we come across analyzes that primarily focus on the problems of indebtedness of non-financial corporations and work with data from national accounts as well as data from other business surveys.

The basics of sectoral analyses based on national account data are generally presented in Lequiller and Blades (2014) . Chapter 6 is the analysis of the behaviour of non-financial corporations where the basic relative indicators are presented and their informativeness is described. Basic approaches to the analysis of the financial accounts of the non-financial corporations are presented by Van de Ven and Fano (2017) . The authors explained the principles, concepts and definitions related to the financial accounts and focused on the possibilities of measuring financial risks and vulnerabilities. According to Eurostat (2013) both of these important works are based on the general principles of national accounts.

Ilyés and Ilyés-Molnár (2014) focused on the analysis of data from the financial account of non-financial enterprises. The aim of this study was to determine potential regularities in the economic behaviour of non-financial enterprises based on time series analysis. Using the example of Bulgaria, Hristozov (2020) dealt with the importance of monitoring the indebtedness of the non-financial enterprises by using relative indicators. It proves that it is necessary to combine absolute and relative indicators and assess their values in connection with other indicators at the macro level.

Salas-Fumás (2021) emphasizes the importance of national accounts data for analysing the economic behaviour of non-financial corporations. He investigates whether Spanish non-financial corporations (especially after the stagnation due to the COVID pandemic) are able to meet the new requirements for the digital and green economies. Using absolute and relative indicators based on sector data and other complementary indicators, he assesses the vulnerability and resilience of Spanish non-financial corporations in crisis situations (the financial crisis of 2008-2012 and pandemic of 2020-2021).

Menandes, Gorris, and Dejuan (2017) have also researched the Spanish non- financial economics firms through the crisis years. They examined the 2008-2013 crisis period and demonstrated that the Eurozone countries’ economic performance of non- financial firms was not affected in the same way. They used national accounts data as well as data from other sources (CBSO 4, Amadeus database) for their analysis and showed that Spanish and Irish non-financial corporations (especially in the construction and real estate market) were badly affected by the crisis. Spanish non-financial corporations experienced another recession in 2013 following a brief recovery in 2010. The decline in their profitability was significantly higher than for non-financial corporations in other Eurozone countries.

Grieder and Lipsitz (2018) also evaluated the crisis resilience (conversely, vulnerability) of non- financial firms. After 2011 (mainly due to the oil price rise), Canadian non-financial corporations' indebtedness (relative to GDP) increase steadily. Therefore, they constructed indicators of the vulnerability of non-financial firms based on national accounts and company-level data and showed that it is development in the extractive industries that has the most significant impact on the vulnerability of non-financial firms and in particular on their indebtedness.

Cussen and O´Leary (2013) conducted a study on the indebtedness of Irish non-financial corporations which is highest in Europe. These authors explain the specificities of Ireland's economic development by using relative indicators based on national accounts that the indebtedness of Irish non-financial corporations is higher than the European average when debt indicators are constructed in relation to GDP. However, when their debts are expressed in relation to balance sheet items, the situation is different. This discrepancy is a consequence of the increasing presence of multinational corporations in the Irish economy. As a result, non-financial corporations reduce their liabilities towards domestic banking institutions and borrow from non-residents.

Van Nieuwenhuyze (2013) focused on the analysis of the indebtedness of non-financial corporations. He noted that the indebtedness of governments has received a lot of attention but the issue of other sectors' indebtedness (or their ability/inability to repay their obligations) is often neglected. The paper is a comprehensive analysis of the debt circumstances of governments as well as households and non-financial corporations in the Eurozone countries and shows that these countries considerably differ among themselves in terms of their total net debt (i.e., a country's debt with respect to the rest of the world). This emphasise the importance of low indebtedness of households and non-financial corporations and on the other hand, the "covering" of government debt by domestic financial assets.

Hronova and Hindls (2012) examined the behaviour of Czech non-financial corporations in the crisis years. The authors highlighted the difference in economic conditions in the second half of the 1990s and in the crisis years 2009-2012 and showed through a detailed analysis based on national accounts data. The main factor behind the difference in the economic performance of Czech non-financial corporations in these two crisis phases was their level of indebtedness and vulnerability. The impact of the 2009 crisis on the small business sub-sector of the household sector in the Czech Republic was discussed by Hronová, Hindls, and Marek (2016) . They showed that, with the onset of crisis symptoms, producers immediately cut costs and investments and tried not to increase their indebtedness.

The ability to deal with crisis situations is the subject of a study by Siuda (2022) provide a methodology called stress tests for Czech non-financial corporations based on input-output analysis and uses relative indicators based on national accounts data. The starting point is the formulation of a macroeconomic scenario that defines the type of risk being tested and the degree of simulated stress. Such a scenario usually captures the most important risks that could have a severe impact on non-financial corporations in particular on their indebtedness and indirectly on the financial system as a whole. Sedlacek and Popelkova (2020) also deal with the situation of Czech non-financial companies and analyzed the impact of mandatory disclosure of non-financial information in the statements of Czech corporations.

Another group of work focuses on the analysis of microeconomic data for a set of non-financial corporations. However, their goal is also to describe economic behaviour, their vulnerability or reaction capacity in the case of changes in input conditions. Martinez-Carrascal and Ferrando (2008) showed to what extent changes in the investment rate of non-financial enterprises are influenced by their financial position. The Netherlands and Italy had larger investment rate as compared to Germany. A similar problem is addressed by Coluzzi, Ferrando, and Martinez-Carrascal (2009) who examined the dependence of the economic growth of non-financial corporations on various factors of their financial position. The impact of legislative changes on the behaviour of non-financial corporations in Spain is discussed by Sierra-Garcia, Garcia-Benau, and Bollas-Araya (2018) .

Dungey, Flavin, O'Connor, and Wosser (2022) dealt with issues of assessing the systemic risk of US non-financial corporations. They analysed the development of the values of two indicators of the rate of systemic risk of selected non-financial corporations and confirmed that the monitored enterprises were vulnerable to systemic shocks. The variability of values in time and space led them to the conclusion of the necessity of using both proposed indicators for assessing the level of systemic risk. Roulet (2020) analysed the level of indebtedness of non-financial corporations by using stress tests to examines the sensitivity of corporate debt to potential macroeconomic and financial shocks. Alvarez (2015) deals with issues of inequality in the distribution of profits and their impact on the structure of expenses of non-financial enterprises in France. It is concluded that increased dependence on financial profits is likely to reduce the share of wages in non-financial enterprises and worsen the labour bargaining position in income distribution.

Barajas, Restrepo, Steiner, Medellin, and Pabón (2016) used logit and probit analysis to identify macroeconomic and microeconomic factors affecting the financial position of Colombian non-financial corporations. Benatti, Ferrando, and Lamarche (2015) based their study on the fact that the use of micro data encounters problems with confidentiality. Based on probabilistic models, they designed a tool to analyse non-financial corporations even when firm-level data are not available.

While approaches to analysing the economic behaviour of non-financial corporations based on macroeconomic or microeconomic data vary. They always aim at highlighting the key role of this sector in the national economy.

3. Specifics of the Crises in the Czech Republic – Economic Context

Fundamental changes in internal and external economic and political conditions (price liberalisation, privatisation, restrictive financial policies, market collapse in the former Soviet bloc countries) were the causes of the decline especially in industrial production whose fall was more significant (12.9% decline) than that of the economy as a whole (10.0% decline in GDP). The price liberalisation triggered price increases and was the main cause of high inflation rate values in the early 1990s (56.6% in 1991, 11.1% in 1992 and 20.8% in 1993).

The Czech National Bank continued to maintain a fixed exchange rate regime with an oscillation band of ± 2.5% which logically led to a speculative attack on the Czech Crown. The liberalisation of capital movements, the stable exchange rate and the high interest rate differential meant that speculative short-term capital began to flow into the Czech Republic to a considerable extent in the mid-1990s. The money supply and the volume of domestic credit increased dramatically. As a result of the capital inflow, high inflation and high interest rates persisted. Massive capital inflows led to risk-taking behaviour in the banking sector where toxic loans accumulated (their proportion in total loans in the Czech Republic exceeded 33%). This led to the collapse of a number of banks and a significant decline in investor interest in the non-financial corporate sector.

Economic growth in the Czech Republic which peaked in 1995 (GDP growth of 6.4%) was mainly offset by the deterioration in foreign trade relations. The high annual growth rate of industrial and construction production (more than 13% in each sector) requires the rapid and high-quality provision of inputs. These circumstances together with the growing purchasing power of the population and the vulnerability of Czech export enterprises put pressure on the disparity between imports and exports – the trade deficit tripled compared to the previous year. On the other hand, the volume of foreign direct investments (mainly in telecommunications and petrochemicals) also tripled. Insufficient support for domestic especially exporting enterprises, a very restrictive anti-inflationary and budget policy and increasingly frequent bank failures were indications of the imbalances in the Czech economy which later manifested themselves in an unexpected downturn in 1997-1998.

The depth of economic crisis was a resulted of hurried and poorly managed privatisation, insufficient enforcement of commercial law, poor bank management, slow progress in industrial restructuring and the central bank's extremely strict anti-inflation policy. Bank financing was too expensive, making it unavailable to businesses and the capital market failed to perform its function. As a result, construction output decreased in 1997 (-2.6%) and export and import growth also decreased. Although the trade and balance-of-payments deficits decline, the government budget deficit almost doubled. There had been a considerable rise in business bankruptcies and the unemployment rate had reached 10% by the end of the year. Demand for consumer goods was severely affected by the decline in the real income and unemployment. The fall in consumer prices, triggered by consumer disinterest and the rise of wholesalers meant that the central bank's tough anti-inflationary policy lost its justification. This led to a significant fall in reserve requirements (to 7.5%), interest rates in the last quarter (discount rate 10%, Lombard rate 15%) and towards the end of the year (discount rate 7.5%, Lombard rate 12.5%). However, these measures came too late to reverse the adverse economic trend towards recovery. GDP fell by 0.5% in 1997.

In this situation, economic policy had to look for a very specific way out of the crisis. Namely, it focused on foreign investments, particularly through the system of investment incentives. The inflow of direct foreign investment reached almost USD 6.3 billion in 1999 which represented more than a quarter of the direct foreign investment volume flowing into the Czech Republic since 1991. Foreign investments were mainly directed to privatised banks and enterprises to expand the network of wholesalers, to increase capital in existing joint ventures and to establish new enterprises. The high volume of such investments also represented a major qualitative change in the structure of the balance of payments. This led, among other things, to a change in the central bank's approach towards a fall in interest rates and a reduction in minimum reserve requirements and to the adoption of pro-growth measures by the government aimed at revitalising industry.

The development of the Czech economy after 2000 can be divided into three stages: the recovery phase, which can be considered as the period 2001-2004, the subsequent boom phase in 2005-2007 and finally the crisis years (starting in 2009) and the subsequent fall into recession (2012). However, the first two phases had different features. The year 2004 marked the start of a period of high growth rates and indicated this period's slowdown in household final consumption expenditure (2.8% year-on-year, against a previous 5.2% growth), investment growth (7.5% year-on-year, against a previous year-on-year stagnation) and above all (for the first time since 1993) a positive external trade balance. By contrast, 2007 signalled an "overheating" of the economy – with high annual growth rates of investments (by 14.3%), household final consumption expenditure (by 4.2%), a high deficit of non-financial corporations, the highest increase in the economy's debt position vis-à-vis the rest of the world and a significant advance of wage growth rates over labour productivity growth rates.

The year 2009 marked a fall into negative figures (not only in the Czech Republic) – investments decline by 17.7% year-on-year, household final consumption expenditure also declines (by 0.5%) and the government deficit reached a previously unrecorded CZK5 214 billion (5.9% of GDP). As a result of the decline in industrial and construction production and investments, both exports and imports decline (by 10% year-on-year). Nevertheless, the Czech economy managed to maintain a positive balance of trade and services even with the decline in the volume and dynamics of foreign exchange, even with a slight appreciation of the Czech Crown. The decline in economic activity and the associated rise in unemployment led to an increase in the general government deficit (by 3.4 pp. to 5.4% of GDP) and general government debt (by 5.3 pp. to 33.4% of GDP). The focus of economic policy exclusively on restrictive budgetary policy then caused a temporary recovery phase (2010-2011) and the subsequent fall of the Czech economy back into crisis in 2012 (0.8% decline in GDP).

The development of the Czech economy after 2014 was marked by efforts to consolidate public finances to promote investments especially into transport infrastructure and housing construction and to raise the population's living standard. To reduce the deficit and government debt high public investment and wage in the public sector rise. In 2016, by significantly reducing investments (by more than a third year-on-year or by volume to the 2004 level), the general government thus achieved a transition from traditional deficit to surplus (from -0.6% of GDP in 2015 to 0.7% of GDP in 2016). However, it should be noted that the inflow of EU funds to a considerable extent also contributed to this fact. Government debt decreased (from 40.0% of GDP in 2015 to 36.6% of GDP in 2016) as a result of the large number of long- term securities that were redeemed. With a relatively high GDP growth rate (annual average of 3.6% over the period 2013-2019), a positive external trade balance and sustained growth in household final consumption expenditure (annual average of 3.1% over the period 2013-2019), these positive trends were sustained.

As a result of the global COVID-19 pandemic and related measures, in 2020, GDP decline by 5.8%, household final consumption expenditure by 7.0%, investments by 10.3% and imports and exports by 7%. According to preliminary data, 2021 marked a return to growth, especially in investments and household consumption. However, GDP only reached the level of 2018 (in 2015 prices).

4. Analysis of the Non-Financial Corporations' Sector

The non-financial corporations' sector, from an economic perspective is the most important institutional sector, bringing together entities whose main function is the production of goods and non-financial market services, i.e., market producers in all sectors of the national economy except the financial, insurance and non-market services sectors. The proportion of this sector in GDP in the Czech Republic has long been around 55%.

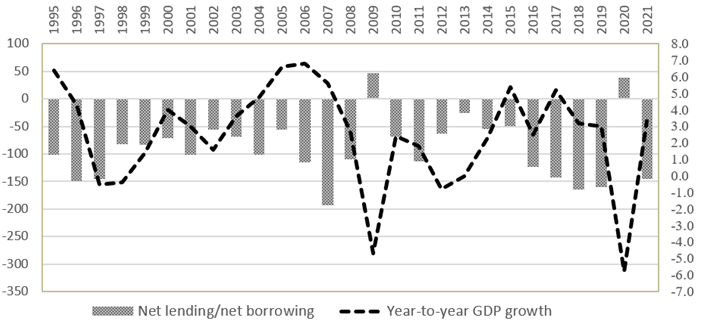

However, the response of Czech non-financial corporations to the different phases of GDP development (see Section 2) has not been unidirectional. If we compare the GDP growth rate and the balance of non-financial corporations (net lending/net borrowing), with a significant decline in GDP (by 4.7% in 2009 and 5.8% in 2020), non-financial corporations achieved a positive balance of operations (CZK 47 billion and CZK 38 billion in 2009 and 2020 respectively). On the other hand, with a lower decline in the economic performance of the national economy (0.5% and 0.8% decline in GDP in 1997 and 2012, respectively), non-financial corporations showed an exceptionally high net borrowing (CZK 145 billion and CZK 63 billion in 1997 and 2012 respectively).6 It is therefore true that internal causes of economic crises are reflected in a lower GDP decline and a high operating deficit of non-financial corporations. External factors of the crises caused a significantly higher year-on-year decline in GDP and high net lending value of non-financial corporations. These relationships are documented in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Development of the economic balance of non-financial corporations (bilion. CZK) and GDP growth rate of the Czech Republic (in %). |

At the same time, it is not possible to focus only on the data for a single year but it is necessary to see the monitored indicators in their dynamics. In addition, the inclusion of relative indicators makes it possible to compare not only in time (we only have data on current prices) but also in space. For time comparison, we have chosen comparable data from 1995 to 2020.

If the sector of non-financial corporations is the most economically significant entity creating more than half of the GDP and a significant investor, then the subject of interest will probably be everything related to added value, its creation and value structure. From the indicators contained in the account of non-financial corporations. It is possible to compile a whole range of relative indicators that characterize the economic behaviour of the units in this sector. We will design these indicators in such a way as to obtain not only an overall picture of the economic behaviour of this sector in the Czech Republic from 1995 to 2020 but mainly to obtain an answer to the question of what is the cause of the different behaviour of Czech non-financial corporations in various types of crises. Relative indicators which are based on national accounts indicators but are designed in a way that make them closer to the conditions for evaluating economic performance in business practice.

4.1. Non-Financial Corporations' Savings and Investments

Net lending and net borrowing can be understood not only as the balance of the non-financial account in each sector but also as the difference between the outcome of current transactions (gross savings) and investments (gross capital formation).7 Gross savings can be understood as the part of gross value added that non-financial enterprises have been able to retain for investments. If we use relative indicators for comparison, it is clear that non-financial corporations will show a net borrowing value if the saving rate (the ratio of gross saving to gross value added) is lower than the investment rate (here the ratio of gross capital formation to gross value added). This was most pronounced for Czech non-financial corporations in the crisis year of 1997 (the difference was -17.6 pp) and in 2012 it was -4.5 pp. On the other hand, it is undoubtedly true that, even with a lower savings rate, a positive economic result can be achieved if the investment rate is also low. This relationship is best illustrated by the self-financing rate which is the ratio of the savings rate to the investment rate, this indicator's value exceeded 100% in 2009 and 2020, whereas the values in 1997 and 2012 were significantly lower (57.1% and 85.4%, respectively). With external signals of the crisis, non-financial corporations appear to quickly respond by reducing investments (with annual drops in the investment rate of 8.6 p.p. (percentage points) and 3.1 p.p. in 2009 and 2020, respectively). These relationships and values are summarised in Table 1.

Year |

Crisis cause | GDP year-on-year growth rate (%) |

NFC8 net lending/net borrowing (bilion CZK) |

Investment self-financing rate (%) |

1997 |

Internal | -0.5 |

-145.2 |

57.1 |

2009 |

External | -4.7 |

+47.1 |

102.3 |

2012 |

Internal | -0.8 |

-63.4 |

85.4 |

2020 |

External | -5.8 |

+38.1 |

100.5 |

Source: www.czso.cz |

The first basic difference in the behaviour of Czech non-financial corporations therefore, logically emerges from a comparison between investments and corporations' own sources of financing.9 However, let us have a more detailed look at whether differences in the economic behaviour of non-financial enterprises in the different periods of the crisis can also be found in the process of their disposable income formation. ( In the case of non-financial enterprises, the volume of savings equals that of the disposable income).

4.2. Creation of Disposable Income

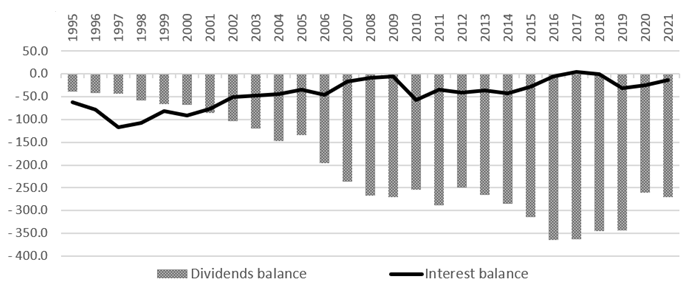

The negative balance of property income has been growing in Czech non-financial corporations. As a result of high interest rates on loans and the growing indebtedness of non-financial corporations which sought sources of financing for their activities due to the poorly functioning capital market, mainly in the area of bank loans, the negative interest balance was the main source of financing for their activities in the 1990s. This was replaced by the balance of distributed income of corporations (dominated by dividends) with the first peak again in 2011 and then in 2016, i.e., in the years of restarted economic growth (albeit moderate) see Figure 2 .

Figure 2. Balance of income from ownership of non-financial corporations in the Czech Republic (bilion CZK). |

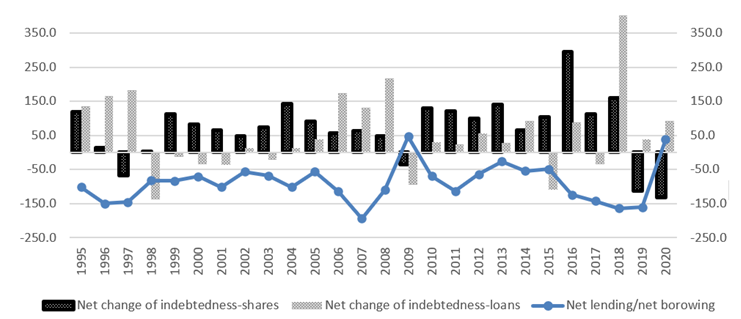

After 2000, Czech non-financial corporations tried to find sources of financing in equity issues and reduce their indebtedness in the form of loans. This can be illustrated by data from the financial account see Figure 3. This data not only explain the disparity between the components of the property income balance but also reveals the desired cause of the significant changes in the net lending and borrowing during the crisis’s various years. Between 1995 and 1997, the indebtedness of non-financial corporations in the form of loans rose with a peak in 1997.It was reflected in the high net borrowing value in these years (-149.7 billion CZK and -145.2 billion. CZK in 1996 and 1997, respectively). This was followed by years of de-leveraging in the form of loans when non-financial corporations turned to seeking the sources of financing mainly in the form of equity issues. A significant increase in indebtedness in the form of loans and participations was recorded in 2006-2008. With the onset of the crisis, on the other hand, there was a sharp reduction in indebtedness both in terms of loans repaid rather than borrowed and shares issued rather than paid up. These factors, together with the other aspects mentioned above on the non-financial side were among the reasons for the record net borrowing in 2007 (CZK -193.6 billion) and, on the other hand, the net lending in 2009 (CZK 47.1 billion).

Figure 3. Net change in indebtedness in the form of shares and loans of non-financial corporations in the Czech Republic (billion CZK). |

The result of the primary and secondary distribution of income is disposable income which in the case of non-financial corporations is equal to their savings. Since non-financial corporations do not participate in the redistribution of income in kind or in final consumption. In the crisis year 1997, non-financial corporations ended up with a surplus on current transactions of only CZK 7.6 billion while in the crisis year 2009 they posted a saving of CZK 63.0 billion. The reason for these diametrically opposed situations lies as our analysis presented above shows in the generation and distribution of income. In 1997, the share of compensation of employees in gross value-added rises by 1.5 percentage points year-on-year (y-o-y), which led to a decline in the net operating surplus (by 3.1%) and the (negative) balances of primary and secondary pensions also rises significantly. In 2009, although the net operating surplus decline (by 14.8% y-o-y), there was also a fall in compensation of employees (by 5.2%).10 This meant that the saving of non-financial corporations fell more in relative terms in 1997 (down 90.3% y-o-y) than in 2009 (down 59.3% y-o-y).11 The high rate of investments in 1997 (41.1%) with a low saving rate (23.5%) than implied a high net borrowing value. Conversely, in 2009, an average savings rate (26.6%) with a below-average investment rate (of 26.0%) led to net lending.

Similar to 1997, internal factors of 2012 crisis and the management of Czech non-financial corporations resulted in net borrowing. The situation of non-financial corporations was favourable from the perspective of current transactions, gross value-added increased year-on-year net operating surplus decreased due to an increase in employee’s compensation net savings increased due to an increase in the collection of property income, or a significant decrease in the negative balance of property income. The resultant negative operational balance was due to the disparity between the savings rate (26.1%) and the investment rate (30.5%). From an economic perspective, 2012 was a failure. However, it was a relatively prosperous year from the perspective of non-financial corporations.

So, what was the cause of the crisis in 2012 and where were its main manifestations? As mentioned in the introduction, the reason for the Czech economy's fall into recession after the 2009 crisis was overly restrictive fiscal policy. The Czech Republic’s high unemployment rate (7%) and economic stagnation were the results of efforts to reduce current and investment public spending. As a result, the government deficit increased by 1.2% yearly to 3.9% of GDP and the government debt increase by (up 4.7 p.p. y-o-y to 44.5% of GDP). The 2012 recession therefore had internal causes, although they were partly an echo of the global crisis of 2009. However, it did not primarily affect non-financial corporations (i.e., the industrial sector) but government institutions (i.e., the public sector). By contrast, the 1997 crisis caught non-financial corporations in a phase of privatisation and restructuring i.e., weakened and completely unprepared for the market environment, moreover, in the context of not fully efficient banks. The impact on their economic performance was therefore very severe. By contrast, in 1997 the government institutions ended with a deficit of 3.1% of GDP and a debt of 13.1% of GDP.

The decline in economic activity throughout the national economy in 2020which was not caused by the economic crisis but rather by the reduction in a variety of activities was the primary factor in the positive balance of the Czech non-financial firms. On the one hand, this evolution led to a 7.0% decline in gross value added produced by Czech non-financial corporations, a 12.9% decline in their net operating surplus and a 7.7% decline in net savings. On the other hand, it resulted in an increase in subsidies and capital transfers received (in the form of compensation for losses caused by the pandemic), a 1.0% decline in compensation paid to employees and a 12.7% decline in investments (gross capital formation).12

4.3. Rates of Indebtedness and Profitability of Non-Financial Corporations

We have dealt with the assessment of data in terms of macroeconomic sector analyses. Let us now try to evaluate the performance of Czech non-financial enterprises using indicators whose definitions are close to corporate practice. The construction of such relative indicator is based on the indicator of net entrepreneurial income of non-financial corporations which is defined as net operating surplus increased by property income received (excluding rents and pensions attributed to insurance policy holders) and reduced by interest and rents paid. Net income of non-financial corporations is conceived in the 'after-tax' version, i.e., after deduction of current taxes paid. This indicator of net income of non-financial corporations is used to construct indicators of non-financial corporations' net debt-to-income ratio after taxes and their net return on equity after taxes. These two indicators help us to illustrate the differences in the economic behaviour of Czech non-financial corporations during the crisis years.

The net debt-to-income ratio after taxes is defined as the ratio of net indebtedness at the end of the year in the form of securities other than shares and loans13 with respect to net entrepreneurial income after taxes. This indicator measures the extent to which non-financial corporations are unable to cover current liabilities from the results of their operating activities.

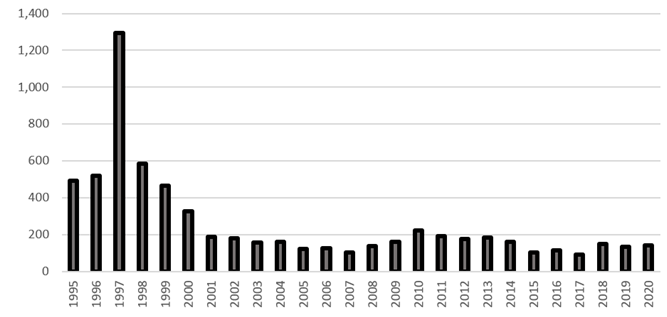

Figure 4. Net debt ratio of non-financial corporations in the Czech Republic (in %). |

The data in Figure 4 clearly illustrates a fundamental difference between the situation of non-financial enterprises in the Czech Republic in the second half of the 1990s and the period after 2000. While net indebtedness exceeded 1,200% in 1997 and increased two-and-a-half times over the previous year, in 2009 it changed only insignificantly compared to 2008 and reached 160%, i.e., the same level as in 2004 which was a year of economic growth. This significant increase in the indebtedness of non-financial corporations in the Czech Republic in 1997 was caused by a halving net income and a more than quarter increase in net indebtedness. Net income mainly declines because of the increase in the volume of interest paid (by 36%). The high year-on-year increase in net indebtedness of non-financial corporations in 1997 was mainly due to a 22% increase in indebtedness in the form of loans.14 Other items of financial assets and liabilities showed little year-on-year change. The lack of financial resources and the need to rely on bank loans at high interest rates were therefore the main causes of the economic problems of non-financial corporations in 1997. Consequently, we can take them as a significant reason for the different performance of non-financial corporations in 1997 as well as in other crisis years15 .

Another indicator based on indicators close to corporate practice is the net return on equity after taxes. This is defined as the ratio of net income after taxes to net debt in the form of shares and other equity.16

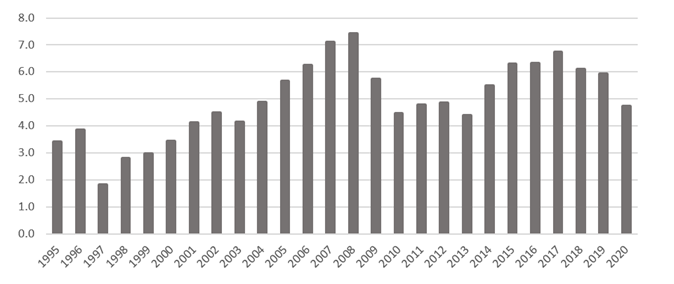

Figure 5. Return on equity of non-financial corporations in the Czech Republic (in %). |

The data in Figure 5 shows that, while in the late 1990s the return on equity of Czech non-financial enterprises was below 4%, its values were significantly higher in the first decade of the 21st century. The cause of the year-on-year decline in the return on own resources in 1997 was exclusively due to the above-mentioned significant fall in net income. By contrast, the profitability of non-financial corporations in 2009 (5.7%) was the same as in 2005, a year of high economic growth (annual GDP growth of 6.6%). The year-on-year decline in return on equity in 2009 was caused by a fall in net income of a fifth (net debt in the form of participations rose by only 2.5%).17

The return on equity fell below the 5% threshold between 2010 and 2013 only to return to it in 2020. Net income did not exceed the 2009 threshold in any of the years 2010-2013 (mainly due to the growth in the negative balance of property income and the fall in the net operating surplus),18 while net debt in the form of participations grew by an average of 3.6% each year. Although the causes of the national economic crisis in the Czech Republic in 1997 and 2012 were internal, the situation was not the same for non-financial corporations. The reasons for the negative results of Czech non-financial corporations reported in the national accounts in 1997 (very low savings, high net borrowing) were their high level of indebtedness and high level of investments. In the case of 2012, the main reason for their negative economic balance can be found in their low economic efficiency (in particular, the decline in net margin and net income).

The year 2020 was marked by a general decline in economic activity as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic. In the case of Czech non-financial corporations, this was reflected in a decline in the return on equity below the 5% threshold. This was mainly due to a decline in efficiency (measured by the net margin) and thus a decline in net income. However, with significant compensation from the state and a decline in investment activity, Czech non-financial corporations managed to achieve a positive balance of operations even with the decline in total production activity.

Thus, indicators close to corporate practice have been of considerable help in understanding the differences in the performance of non-financial corporations in terms of current operations which are concentrated in the national accounts in the savings indicator. Thus, the reasons for the completely different performance of Czech non-financial corporations in the years of the crisis, i.e., the high net borrowing level in 1997 and 2012 (internal causes of the crisis) and the net lending in 2009 and 2020 (external causes) can be sought not only in the different levels of self-financing of investments but also in the different levels of indebtedness and efficiency ratios.

5. Conclusion

The causes and effects of the economic crises in the Czech Republic in the late 1990s and the first two decades of the 21st century were distinct. They all resulted in a loss of dynamism in the national economy and a fall in GDP most significantly in 2009 and 2020. The causes of the crises in 1997 and 2012 were internal problems in the Czech economy and resulted in a slight fall in GDP (by less than 1%). The crises in 2009 and 2020 had external causes and resulted in a significant annual fall in GDP (around 5%).

The main causes of economic transformation in 1997 were incomplete privatisation, slow industrial restructuring, the lack of a concept for the transformation and development of the banking sector with the subsequent collapse of a number of banks, and an overly restrictive monetary policy. The attempt to quickly solve the problem of the transition from a centrally planned to a market economy coupled with the necessary renewal and modernisation of production capacities led to an extremely high volume of investments. It resulted (with a lack of free funds and the virtual absence of a capital market) in serious problems in financing current activities and in high indebtedness of non-financial corporations. These factors with the low efficiency of Czech non-financial corporations led to very low net savings with above-average levels of investments and a high net borrowing value.

The causes of the crisis in 2009 must be sought outside the national economy of the Czech Republic. The credit and financial crisis came from the USA and affected all developed countries even if not simultaneously. Signals of the crisis coming from the external environment were reflected in a cooling of the economy as early as in 2008 (a significant slowdown in the growth rate of investments, imports and exports). On the other hand, this meant that Czech non-financial corporations were able to prepare for the coming crisis phenomena. As a result, although gross value added generated by non-financial corporations fell in 2009, employment was also being cut, compensation to employees fell and the volume of non-financial and financial investments become lower. All this ultimately led to non-financial corporation ending up with a funding capacity, i.e., a surplus of resources, in the crisis years (for the first time since 1995). From a macroeconomic perspective, however, this was a feature of negative economic behaviour, reducing the overall performance of the national economy.

The fall in economic activity, the rise in unemployment and the stagnation in household final consumption expenditure led to lower tax collection and increased non-investment spending by the government. The 2009 crisis thus hit the general government the hardest and was reflected in high general government deficits and rising general government debt. Under the threat of the 'Greek scenario', economic policy in the Czech Republic exclusively focused on the recovery of public finances, meaning a very restrictive fiscal policy, disregarding other macroeconomic parameters and completely stifling the necessary recovery. This evolution in effect led to a recession or a return to crisis in 2012.

The fall in GDP in 2012, which was caused internally, was weaker compared to 2009, but was reflected in an overall loss of confidence, especially on the consumer side. This naturally had an impact on the fall in final consumption expenditure by households and governments and on the decline in public investments. The situation was different for non-financial corporations. Moderate growth in gross value added and savings led to the ability to finance higher levels of investment in the face of low interest rates on credit. The main reasons for non-financial corporations' net borrowing in that year were the increase in indebtedness and the high level of investments.

A change in the focus of economic policy (support for public and private investments, increase in public wages) helped to kick-start the recovery in the Czech Republic in 2014 (average annual GDP growth rate in 2014-2019 was 3.6%), which was ended by the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. Imports, exports, investments, household consumption and the output of a number of sectors declined as a result of the downturn in consumption and in a number of productive activities (transport, trade, services, hotels, restaurants, tourism, etc.). The sector most affected by this crisis was (by analogy with the 2009 crisis) the government (moving from a surplus to a deficit of 5.8% of GDP, with a 7.6 p.p. increase in debt to GDP). Non-financial corporations were forced to slow down their activities but the decline in gross value added and savings (inter alia due to government compensation) was less significant than the decline in investments. The excess of the saving rate over the investment rate with the debt ratio unchanged, led to a positive balance in the economy.

The external causes of the crises (2009 and 2020) therefore placed an enormous burden on the state, the government has always emerged from these crises as the entity that seeks to mitigate their impact on the domestic economy through its actions. On the other hand, non-financial corporations emerge from these situations with a positive economic balance, mainly due to the reductions in current and capital expenditure.

The internal causes of the crisis (1997 and 2012) led to a negative balance for non-financial corporations, although the causes and consequences were not the same. In the case of 1997, the non-financial corporations' sector was severely weakened by the ongoing economic transition and was also indebted and unprofitable. The consequence was a very high net borrowing level. In 2012, on the other hand, the non-financial corporations’ sector was consolidated and, in a recession, (which was reflected in a significant deterioration in the deficit and government debt) with low inflation and stagnating wages, they were the entities that helped to start the recovery but at the cost of the net borrowing.

The different performances of Czech non-financial corporations in the crisis years can be described by a number of relative indicators directly based on national account indicators. The values of these indicators help us to explain some of the differences but fail to more accurately capture the different economic conditions in which Czech non-financial corporations found themselves in the years under review. These aspects are better captured by the relative indicators which are also based on the national account indicators but constructed in a way that their explanatory power is closer to the conditions for assessing economic performance in corporate practice. It has thus turned out that the main differences in conditions are hidden in the levels of indebtedness and profitability.

References

Alvarez, I. (2015). Financialization, non-financial corporations and income inequality: The case of France. Socio-Economic Review, 13(3), 449-475.Available at: https://doi.org/10.1093/ser/mwv007.

Banco, D. P. (2016). Sectoral analysis of non-financial corporations in portugal 2011-2016. Central balance sheet studies 26. Lisabon: Banco de Portugal.

Barajas, A., Restrepo, S., Steiner, R., Medellin, J. C., & Pabón, C. (2016). Balance sheet effects in colombian non-financial firms. IDB Working Paper No. 740.

Benatti, N., Ferrando, A., & Lamarche, P. (2015). Firms’ financial statements and competitiveness: An analysis for european non-financial corporations using micro-mased data. IFC Bulletin No. 39.

Coluzzi, C., Ferrando, A., & Martinez-Carrascal, C. (2009). Financing obstacles and growth: An analysis for euro area non-financial corporations. ECB Working Paper, No. 997.

Cussen, M., & O´Leary, B. (2013). Why are Irish non-financial corporations so indebted? Quarterly bulletin 01. Central Bank of Ireland.

Dungey, M., Flavin, T., O'Connor, T., & Wosser, M. (2022). Non-financial corporations and systemic risk. Journal of Corporate Finance, 72(C), 102-129.Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcorpfin.2021.102129.

Eurostat. (2013). European system of accounts – ESA 2010. Luxemburg: Eurostat.

Eurostat. (2021). Non-financial corporations – statistics on profit financial assets and liabilities. Eurostat – Statistics Explained. Retrieved from: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=Non-financial_corporations_-_statistics_on_profits_and_investment&oldid=565251.

Eurostat. (2022). Non-financial corporations – statistics on profit and investment. Eurostat – Statistics Explained. Retrieved from: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=Non-financial_corporations_-_statistics_on_profits_and_investment.

Grieder, T., & Lipsitz, M. (2018). Measuring vulnerabilities in the non-financial corporate sector using Industry- and firm-level data. Bank of Canada: Staff Analytical Note.

Hristozov, Y. (2020). Corporate indebtedness of non-financial corporations in bulgaria. Economic Alternatives, 26(4), 536-566.Available at: https://doi.org/10.37075/ea.2020.4.03.

Hronova, S., & Hindls, R. (2012). Economic crises in the results of the non-financial corporations sector in the Czech Republic. Statistika, 49(3), 4-18.

Hronová, S., Hindls, R., & Marek, L. (2016). Reflection of the economic crisis in the consumer and entrepreneurs subsectors. Statistika: Statistics and Economy Journal, 96(3), 4-21.

Hronová, S., Marek, L., & Hindls, R. (2022). The impact of consumption smoothing on the development of the Czech economy in the most recent 30 years. Statistika: Statistics and Economy Journal, 102(1), 5-19.

Ilyés, C., & Ilyés-Molnár, E. (2014). Statistical analysis of financial accounts in case of non-financial corporations. European Scientific Journal, Special Edition, 1, 44-49.

Lequiller, F., & Blades, D. (2014). Understanding national accounts: Second edition. Paris: OECD Publishing.

Martinez-Carrascal, C., & Ferrando, A. (2008). The impact of financial position on investment: An analysis for non-financial corporations in the euro area. ECB Working Paper, No. 943.

Menandes, A., Gorris, A., & Dejuan, D. (2017). Economic and financial performance of Spanish non-financial corporations during the economic crisis and the first years of recovery. A comparative analysis with euro area. Banco de Espana: Economic Bulletin 2.

Roulet, C. (2020). Corporate debt stress testing: A global analysis of non-financial corporations. Paris: OECD Publishing OECD Working Papers on Finance, Insurance and Private Pensions, No. 46.

Salas-Fumás, V. (2021). Spanish non-financial corporations and the COVID pandemic: Vulnerability, resilience and transformation. Applied Economic Analysis, 29(85), 42-57.Available at: https://doi.org/10.1108/aea-11-2020-0157.

Sedlacek, J., & Popelkova, V. (2020). Non-financial information and their reporting--evidence of small and medium-sized enterprises and large corporations on the Czech capital market. National Accounting Review, 2(2), 204-217.Available at: https://doi.org/10.3934/nar.2020012.

Sierra-Garcia, L., Garcia-Benau, M. A., & Bollas-Araya, H. M. (2018). Empirical analysis of non-financial reporting by Spanish companies. Administrative Sciences, 8(3), 1-17.Available at: https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci8030029.

Siuda, V. (2022). Stress testing of non-financial corporate sector: A top-down input-output framework. Politická Ekonomie, 70(2), 158-192.Available at: https://doi.org/10.18267/j.polek.1345.

Van de Ven, P., & Fano, D. (2017). Understanding financial accounts. Paris: OECD Publishing.

Van Nieuwenhuyze, C. (2013). Debt, assets and imbalances in the euro area. An aggregate view. OFCE Magazine, 127(1), 123-152.Available at: https://doi.org/10.3917/reof.127.0123.

Footnotes:

1 The text of this paragraph is processed according to Hronová, Marek, and Hindls (2022), p. 5.

2 The text of this paragraph is processed according to Hronová et al. (2022), p. 6.

3 Similar trends, i.e. the high net borrowing value in 2008 and the subsequent transition to net lending, can be documented in data from other countries. Let us mention, for example, Slovakia, Austria or the Eurozone as a whole. In Germany, non-financial corporations have been reporting funding capacity continuously since 2004; they only recorded net borrowing in 2008 and subsequently showed a significantly higher net lending in 2009 than in 2007. French non-financial corporations, which have been reporting net borrowing for a long time and reached their highest value in 2008, also managed to achieve a positive result in 2009. Non-financial corporations in the countries concerned (with the exception of France) also showed net borrowing in 2020.

4 CBSO = Central Balance Sheet Data Office.

5 CZK = Czech crown.

6 Non-financial corporations economic balance data are given in current prices.

7 Here the authors deliberately make a simplification in terms of the scale of total investment; gross capital formation would be acquisitions less disposals of non-produced assets. However, the values of this indicator are negligible next to those of gross capital formation.

8 NFC = Non-financial corporations.

11 All in current prices.

12 All in current prices.

13 This is the difference between the year-end balance of liabilities in the form of securities other than shares (excluding financial derivatives) and the balance of claims in the form of loans, currency, deposits and securities (excluding financial derivatives). For more details see Hronova and Hindls (2012), p. 13.

15 For more details see Hronova and Hindls (2012), p. 14.

16 Net debt in the form of shares is the difference between the stock of liabilities and claims in the form of shares at the end of the year. For more details see Hronova and Hindls (2012), p. 14.

18 The net margin rate (the ratio of net operating surplus to net value added) fell in 2012 compared to 2009 by 3.3 p.p.