Monetary – Fiscal Policy Mix: A Tool for Economic Stabilization in Nigeria

Abraham O. Agbonkhese1*

Blessing O. Oligbi2

1Department of Economics, Admiralty University of Nigeria, Ibusa, Delta State, Nigeria.

2Department of Economics and Development Studies, Igbinedion University, Okada, Nigeria.

|

Abstract

The study examined empirically the relationship between monetary-fiscal policy mix and Nigeria’s economic stability. The Johansen co-integration technique complemented with VECM were employed to achieve the objective of the study. The result of the descriptive statistics revealed that the variables were normally distributed and the degree of variability of them was good as evident from the Jarque-Bera statistics and standard deviation. The Johansen and Juselius co-integration results revealed that both the trace statistic and maximum Eigenvalue statistic confirmed the existence of co-integrating equations among the variables of interest. It was evident that the trace test indicated six co-integrating equations while maximum Eigenvalue test revealed four co-integrating equations in the model, as the null hypothesis of no co-integration was rejected. These results suggested that there was a unique long run equilibrium relationship among the variables. The VECM result indicated that there was a long run relationship between the variables concerned. The result further showed that monetary-fiscal indicators have not made much significant contributions to the growth of the Nigerian economy as well as economic stabilization in Nigeria. The study recommended the entrenchment of fiscal discipline as a result of destabilizing effect of government’s fiscal activities due to its fiscal irresponsibility in Nigeria. Also recommended was that monetary policies should be structured to lower lending interest rate and raise interest rate on saving deposits so as to increase the availability of loanable funds which will in turn boost investment and stimulate economic growth. |

Licensed:

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License. |

Keywords:

Monetary-Fiscal policy mix

Economic stabilization Nigeria. |

Accepted: 30 December 2019

Published: 17 January 2020

|

| (* Corresponding Author) |

Funding: This study received no specific financial support. |

Competing Interests:The authors declare that they have no competing interests. |

Acknowledgement:The authors are deeply grateful to the anonymous referees of this paper who made comments that were very useful in revising and improving the quality of the paper. We say thank you all. |

1. Introduction

The Nigerian economy has been plagued with several challenges over the years. In spite of many and frequently changing fiscal, monetary and other macroeconomic policies, Nigeria has not been able to harness her economic potentials for rapid economic development (Ogbole, 2010). According to Adeoye (2006) the debate on the effectiveness of fiscal policy as a tool for promoting growth and development remains inconclusive, given the conflicting results of current studies.

Over the last decade, the growth impact of fiscal policy has generated large volume of both theoretical and empirical literature. However, most of these studies paid more attention to developed economies and the inclusion of developing countries in case of cross-country studies were mainly to generate enough degrees of freedom in the course of statistical analysis (Aregbenyen, 2007).

Fiscal and monetary policies are inextricably linked in macroeconomic management; developments in one sector directly affect developments in the other. Undoubtedly, fiscal policy is central to the health of any economy, as government’s power to tax and to spend affects the disposable income of citizens and corporations, as well as the general business climate. Monetarist strongly believes that monetary policy exact greater impact on economic activity as unanticipated change in the stock of money affects output and growth that is, the stock of money must increase unexpectedly for central bank to promote economic growth. In fact, they are of the opinion that an increase in government spending would crowd out private sector and such can outweigh any short-term benefits of an expansionary fiscal policy (Adefeso & Mobolaji, 2010).

On the other hand, the concept of liquidity trap which is a situation in which real interest rates cannot be reduced by any action of the monetary authorities was introduced by Keynesian economics. Hence, at liquidity trap an increase in the money supply would not stimulate economic growth because of the downward pressure of investment owing to insensitivity of interest rate to money supply. John Maynard Keynes recommends fiscal policy by stimulating aggregate demand in order to curtail unemployment and reducing it in order to control inflation. While there are several studies on this debates between Keynesian and Monetarist in the developed countries, only fragmented evidence have been provided on this issues in the case of Nigeria (Adefeso & Mobolaji, 2010).

Today, monetary and fiscal mix are both commonly accorded prominent roles in the pursuit of macroeconomic stabilization in developing countries, but the relative importance of these policies has been a serious debate between the Keynesians and the monetarists. The monetarists believe that monetary policy exert greater impact on economic activity while the Keynesian believe that fiscal policy rather than the monetary policy exert greater influence on economic activity. Despite their demonstrated efficacy in other economies as policies that exert influence on economic activities, both policies have not been sufficiently or adequately used in Nigeria (Ajisafe & Folorunso, 2002). The objective of this paper is to review the practice of monetary and fiscal policies in Nigeria.

Despite government efforts in the last few years to evolve a suitable monetary and fiscal policies framework in order to enjoy some macroeconomic advantages, objectives desired have not been achieved and the war against inflation, price stability, full employment have not been won; while exchange rate and economic growth have remained unstable. Fiscal expansion and the concomitant large fiscal deficits have militated against the efficacy of monetary and exchange rate policy in Nigeria. Government fiscal operation especially inflationary financing of large budgetary deficits and monetary deficits have continued to pose serious challenges to monetary management.

The setting of high interest rate by the Central Bank of Nigeria and the establishment of Single Treasury Account ( TSA), as well as the sales of treasury bills and government bonds to reduce money supply in order to reduce inflation have been unsuccessful. Also, the operation of the Federal, States and Local governments in Nigeria in terms of their fiscal operations have put a lot of constraints on CBN’s ability to control the amount of money in circulation. There is a consensus in the literature that an inefficient payment system distorts the transmission mechanism of the monetary policy in Nigeria, which invariably undermines the efficacy of monetary and fiscal policy instruments. The allocation of huge amount of money on consumption as well as the poor tax system shows that the government is fiscally undisciplined.

To realize macroeconomic stability, there is the need to harmonize monetary and fiscal policies to solve the macroeconomic problems of the economy. It is the awareness of these problems that trigger off the study in order to examine ways and means in which the monetary and fiscal strategies can be used to the best advantages. To this end, this study intends to investigate the extent to which monetary and fiscal policies affect economic growth in Nigeria.

In light of the foregoing, this study aims at evaluating the link between monetary – fiscal policy mix and economic growth in Nigeria. The specific objective of the study is to determine the long run relationship between monetary - fiscal policy mix and economic stabilization in Nigeria. The study uses annual data from Nigeria for a period of 32 years covering 1986-2017. A number of macroeconomic variables, specifically monetary and fiscal indicators will be used. The choice of this sample period is informed by the fact that, the growth of any economy depends on how the monetary and fiscal policies of such an economy inclusive of Nigeria are implemented for optimal result(s). This is particularly important to the Nigerian economy that is presently facing a myriad of macroeconomic problems. The data will be sourced from various issues of the Central Bank of Nigeria (CBN) Statistical Bulletin, Financial Reviews and Annual Report and Statement of Accounts.

Following the introductory section is the literature review in section two. Section three provides the research methodology and model specification. While section four presents the analyses of estimated results. Section five contains policy recommendations and conclusion.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Conceptual Framework on Monetary and Fiscal Policy

The domestic economy can be divided into two sectors: the real sector or the product market and the monetary sector or the money market. The study considered a framework, called the functioning of an economic system and their interrelationship.

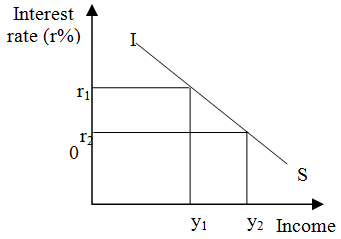

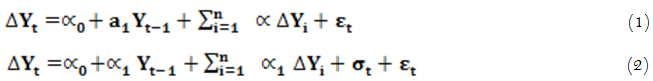

The is Curve and Equilibrium in the Product Market:The is curve is the locus of various combinations of interest rate (r) and income level (Y) that yields equilibrium in the real sector, that equates aggregate expenditure to aggregate output. Equilibrium in the product market is achieved when aggregate expenditure for a given period is equal to aggregate output for that period. The relationship between interest rate and income level is inverse which can be illustrated by a downward sloping curve which depicts the higher the rate of interest, the lower would be the income level and vice-versa.

To illustrate, if we assume an increase in income with all factors remaining constant, this will lead to increase in the level of aggregate savings. The increase in savings would create disequilibrium in the real sector, unless accompanied by an increase in investment. For investment to rise to the level of saving however, the rate of interest must fall. Thus, the increase in income must be accompanied by a fall in the interest rate for investment to equate savings at this new level. The locus of all such various combinations of income and interest rate that equates savings to investment gives us the I-S curve. The diagram below illustrates the IS curve:

From the Figure 1 above, the horizontal axis measures the income level while the vertical axis measures the rate of interest. The equilibrium point is where the interest rate and the level of income are equal. When interest rate falls from r1 to r2, the level of income rises from y1 to y2. This illustrates the inverse relationship between income and the rate of interest.

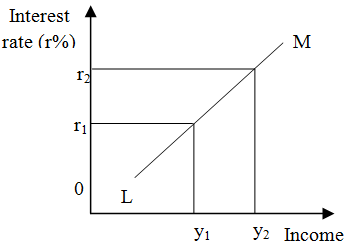

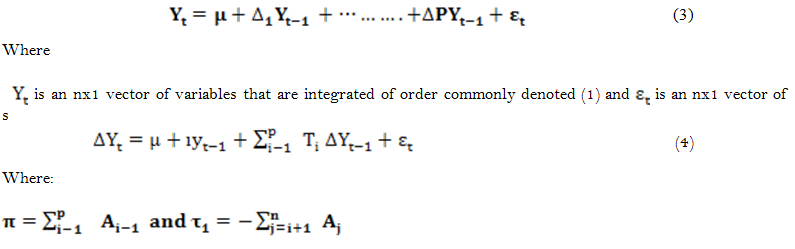

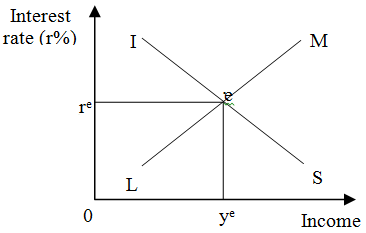

The LM Curve and Equilibrium in the Monetary Sector: The LM curve shows the various combinations of interest rate and income that will yield equilibrium in the monetary sector, which equates the money demand to the money supply. Equilibrium in the money market is achieved when money supply for a given period is equal to the demand for money. The relationship between the interest rate and the level of income in relation to changes in the demand for money is positive and is illustrated by an upward sloping curve which translates to, the higher the level of income, the higher the interest rate and vice versa. Assuming that there is an increase in the level of income, the stock of money supply remaining constant, for the quantity of money demanded to remain equal to the constant money supply, the rate of interest must increase at this new level of income, otherwise, the demand for money would increase leading to monetary disequilibrium. The figure below illustrates the LM curve.

From the Figure 2 above, the horizontal axis measures the level of income while the vertical axis measures the rate of interest. The equilibrium point is where the rate of interest and the level of income are equilibrated. With a rise in income level to y2, the rate of interest also rises from r1 to r2. This shows the direct (positive) relationship between income level and the rate of interest.

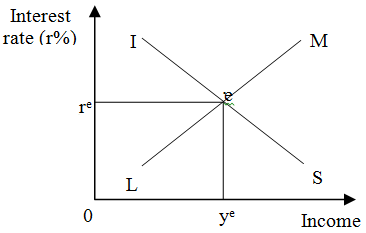

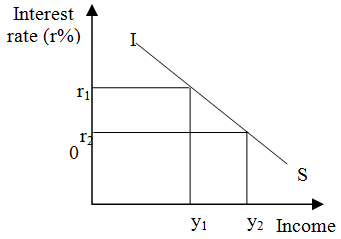

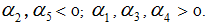

The IS-LM Curves and Simultaneous Equilibrium in the Real and Monetary Sector: Since interest rate and the level of income determine equilibrium in both the real and monetary sectors, it is possible to determine a combination of interest rate and income that will achieve equilibrium simultaneously in both sectors. In particular, the rate of interest and the level of income that corresponds to the point of intersection of the IS and LM curves shows the income level and interest rate required to achieve simultaneous equilibrium in both markets. Any other combination of interest rate and income cannot achieve simultaneous equilibrium in both markets, even though such combinations might achieve equilibrium in one of the two markets.

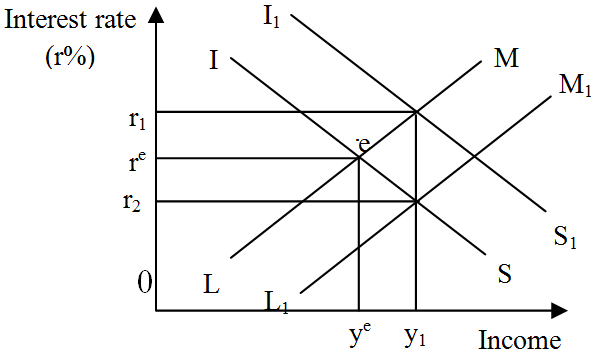

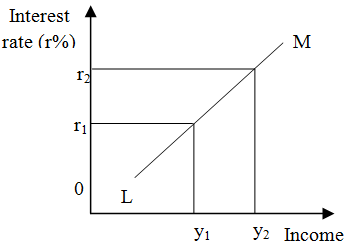

The IS-LM framework shows that both the real and monetary variables, that is, fiscal and monetary policies are important in determining interest rate and income. In particular, an expansionary fiscal policy, that is, an increase in government expenditure or a reduction in taxes, would shift the IS curve to the right indicating an increase in the level of income and the interest rate while a contractionary fiscal policy would shift the IS curve to the left and leads to a fall in income and interest rate. On the other hand, an expansionary monetary policy, that is, an increase in money supply would shift the LM curve to the right indicating a rise in income and a fell in the rate of interest while a contractionary monetary policy would shift the LM curve to the left leading to a fall in the level of income and an increase in the rate of interest. Thus, given normally shaped IS and LM curves, both fiscal and monetary policies have the same effect on the level of national income but different effects on the rate of interest.

Figure-3. Simultaneous equilibrium in the real and monetary sector.

Figure-4. Effects of policy induced shifts in the IS-LM curves.

From the Figures 3, 4 above, simultaneous equilibrium in both the real and monetary sector is achieved at the point of intersection of the IS and LM curve, that is, point e. At this point, aggregate demand is equal to aggregate supply and the demand for money is equal to the supply of money. An expansionary fiscal policy shifts the IS curve to the right, from IS to IS1 which translates to an increase in the rate of interest from re to r1and income level from ye to y1 and vice versa. On the other hand, an expansionary monetary policy shifts the LM curve to the right (outward) which leads to a decrease in interest rate from re to r2 and an increase in income from ye to y1.

2.2. The Theories of Monetary and Fiscal Policies

Historically, there has been a wide divergence of opinions about the effect of monetary and fiscal policies on the economy. These theories were developed basically on observed economic trend in both developed and developing countries. The main burden of macroeconomic policy fell on either monetary or fiscal policy or on the combination of both, there is a controversy about the two, known as monetarists and fiscalist debate. In 1990, Milton Friedman and some economists in Chicago conducted a study to determine whether the Keynesian multipliers or the velocity variables of the quantity theory would serve as a forecasted of the movement of National Income. They did this by testing the stability of the two variables believing that, if the velocity of money is relatively stable changes in the money stock would support the monetarists view. If the investment (Government expenditure) multipliers were more stable, it would indicate that a change in aggregate demand imposed by Federal policy result in a more predictable changes in National Income.

The Keynesian: The basic proportion of this school of thought is that money does not matter in the short-run. Money supply transmission mechanism, they argue that an indirect process working through the cost of capital channel via rate of interest hence supply and income level affects change in money supply appears to be compatible.

Keynesian is essentially based on the short period consideration when money flow rather than stock becomes a crucial variable. Here, the concept of the short-run is similar to the one applicable to the theory of the firm. To the Keynesians, budgetary policy has significant effect on income, employment and output in the short-run, even if there is no new money supply. In fact, public debt is as crucial as the stock of money. An increase in the growth of interest bearing debt would result in an increase in the equilibrium growth of minimal income, without a corresponding increase in the rate of money expansion. The balanced budget multiplier can give the economy substantial leeway for growth while government deficit is expansionary.

The Monetarist: Monetarism’s essence can be stated in the form of a few central propositions where the over-whelming influence of money is the center piece. Monetarists assign causal role to money, and since money is treated by them as exogenous, it is possible to control disturbance or disequilibrium in the economy by controlling the money supply, and hence money matters. To them, fiscal policy is very complicated and difficult to execute in timely manner and given the constancy of the rate of interest over a long period, suggesting horizontal curve (indicating infinitely elastic demand for new investment) and constant money supply, an increase in government investment will correspondingly reduce private investment, and this crowding out’ will reduce the efficacy of fiscal policy. As a result of this crowding out, the effect of fiscal policy on normal income will be zero, provided the LM curve is vertical. An increase in taxation and ‘crowding out’ will raise the rate of interest to decrease the investment. Thus, to them, fiscal policy may change income, velocity, interest rate and so on but its expansionary effect is likely to be minor and transitory (temporary) on aggregate income and price levels. Thus, a pure fiscal policy does not matter for aggregate demand, nominal income price level.

The St-Louis multiplier has been used to show-that pure fiscal policy has no effect on nominal income. Fiscal policy impact depends on how the government deficit is financed. Finance by money creation (a monetary action) is seen to be more expansionary than what is possible by the manipulation of fiscal tools. Thus, according to monetarism, what matters is the quantity of money created and not how it is created. Monetarists are of the view that money and income are directly correlated. Monetary change affects long-run stock of real capital and hence output. Fluctuation in money, national income is attributed largely on monetary policy whose effect is transmitted to national income both through the bond field and other channels. Thus, the long-run economic activity and nominal income are essentially the function of the stock of money and flows themselves adjust to the stock. The adjustment to change in money involves substitution between money and different types of asset, thus, while wealth effect of a change in money is not of any empirical importance, the substitution effect appears to be given the tendency to assume that money is the only asset, the real balance effect and the wealth effect are also assumed to be tantamount. The monetarists concede a direct nexus between money supply and price level, which is proportional in the long-run. In effect, in long-run, proper growth rate of money stock is crucial for stable growth path of output and prices.

2.3. Monetary and Fiscal Policy Coordination

Monetary Policy: Monetary policy are measures taken by the monetary authorities aimed at enhancing economic growth and stability by adjusting the cost and level of money supply, to achieve broad macroeconomics objectives of price stability, output growth and full employment. Mordi (2009) describes monetary policy as a blend of measures or set of instruments designed by the Central Bank to regulate the value, supply and cost of money consistent with the absorptive capacity of the economy or the expected level of economic activity, without necessarily generating undue pressure on domestic prices and exchange rates. By altering the level of money supply in the economy, central banks make money cheaper depending on the absorptive capacity of the economy at a particular point in time. Reaching a balance is especially vital in monetary policy, because a surplus or shortage beyond the optimum level, in the money supply may be detrimental to the realization of the macroeconomic objectives.

Fiscal Policy: Fiscal Policy is the process by which Government uses public expenditure, debt, taxation and other revenues to influence economic activities with a view to achieving the set macroeconomic objectives of full employment, favourable balance of payment, price stability and output growth among others. Idowu (2010) described fiscal policy as the deliberate changes in the levels of government expenditure, taxes and other revenue as well as borrowing with a view to achieving national goals or objectives such as price stability, full employment, economic growth and balance of payments equilibrium. Fiscal Policy could be neutral, expansionary or contractionary. Fiscal policy is considered neutral when government spending is equal to its revenue. This is also known as balanced budget. When government expenditure is fully financed by tax proceeds, the budget has a neutral consequence on economic activities in the country. A government is said to be operating an expansionary fiscal policy when it has a deficit budget. In such a situation, the public expenditure is higher than the tax revenue. This is an advisable policy stance during a period of recession. Recent developments in the global economy especially in the euro area have however, underscored the limitation of deficit financing in an economy. On the other hand, a government with contractionary fiscal policy has a surplus budget such that, public expenditure is lower than tax revenue. This policy stance could be effective in curbing inflation.

2.4. Interaction between Monetary and Fiscal Policies

Fiscal policy and monetary policy are the two tools used by the state to achieve its macroeconomic objectives. While for many countries the main objective of fiscal policy is to increase the aggregate output of the economy, the main objective of the monetary policies is to control the interest and inflation rates. The IS/LM model is one of the models used to depict the effect of policy interactions on aggregate output and interest rates. The fiscal policies have a direct impact on the goods market and the monetary policies have a direct impact on the asset markets; since the two markets are connected to each other via the two macro variables output and interest rates, the policies interact while influencing output and interest rates.

Traditionally, both the policy instruments were under the control of the national governments. Thus traditional analyses were made with respect to the two policy instruments to obtain the optimum policy mix of the two to achieve macroeconomic goals, lest the two policy tools be aimed at mutually inconsistent targets. But more recently, owing to the transfer of control with respect to monetary policy formulation to central banks, formation of monetary unions (like European Monetary Union formed via the Stability and Growth Pact), and attempts being made to form fiscal unions, there has been a significant structural change in the way in which fiscal and monetary policies interact.

There is a dilemma as to whether these two policies are complementary, or act as substitutes to each other for achieving macroeconomic goals. Policy makers are viewed as interacting as strategic substitutes when one policy maker's expansionary (contractionary) policies are countered by another policy maker's contractionary (expansionary) policies. For example: if the fiscal authority raises taxes or cuts spending, then the monetary authority reacts to it by lowering the policy rates and vice versa. If they behave as strategic complements, then an expansionary (contractionary) policy of one authority is met by expansionary (contractionary) policies of the other.

The issue of interaction and the policies being complements or substitutes for each other arises only when the authorities are independent of each other. But when the goals of one authority are made subservient to those of the other, then one authority solely dominates the policy making and no interaction worthy of analysis would arise. Also, fiscal and monetary policies interact only to the extent of influencing the final objective. So long as the objectives of one policy are not influenced by the other, there is no direct interaction between them (https//en.wikipedia.org/wiki).

2.5. Monetary – Fiscal Policy Mix in the Economy

In the economic literature is the concept of policy mix, understood as a combination of fiscal and monetary policy. Kuttner (2002) analyzing the monetary - fiscal interactions underlined the strategic interactions based on different goals and preferences of the independent authorities responsible for the conduct of monetary and fiscal policies. Economists, Sargent and Wallace (1981) developed the "theory of unpleasant monetarist arithmetic” based on the idea that at the time of occurrence of the dominance of fiscal, monetary authorities are no longer able to keep inflation under control, regardless of the strategy to use.

Kuttner (2002) also showed that taking into account the interactions associated with intertemporal budget constraint thought that the form of financing the budget deficit can be a money issue, bonds or a combination of both. It was thought that the bond issue does not lead to an increase in the price level, which is not true, because at the time to take account of rational expectations, it appears that the bond issue may also have inflationary consequences. Hence the conclusion that fiscal policy limits the central bank making decisions, and therefore makes it difficult to stabilize the price level. Different objectives and preferences of the central bank and the fiscal authorities are difficult to stabilize the economy in the short term. The monetary and fiscal authorities set targets its policies and preferences that reflect their aspirations. Reconciliation of action is the right choice for both authorities. Conflict of both policies lead to an increase in the interest rate and the budget deficit. Harmonization of policies eliminates both sources of conflict, leads to minimize maintenance costs and price stability reduces criticism of the government related to the operation of the central bank. Coordination of monetary policy and fiscal policy contributes to greater stability of the financial system (Sargent & Wallace, 1981). The economic literature emphasizes that low economic growth in the euro area is the result of a lack of coordination between monetary and fiscal policy.

According to Blanchard and Giavazzi (2004) inadequacy of institutions of policy mix in the European Monetary Union (EMU) is responsible for the low economic growth because it limits government spending, such as: infrastructure, research and development and higher education that enhance the growth potential of the economy. Hagen and Mundschenk (2003) and Wyplosz (2002) believe that the lack of cooperation hinders the interactions of monetary and fiscal policy, which is reflected in inefficient policy mix. Thus, the monetary and fiscal policies act as strategic substitute rather than complement (Wyplosz, 2002).

2.6. Role of Monetary and Fiscal Policies in the Stabilization Process

The great depression of the 1930s has had a profound influence on both economic and political thinking. The consequences of this event turned out to be of such a dimension that broad consensus emerged on governments doing their best to prevent such disasters from happening again. But even beyond this extreme case, there is general agreement that a stable and predictable economic environment contributes substantially to social and economic welfare. In the short-run, households prefer to have economic stability with continuous employment and stable incomes, allowing them to maintain stable consumption over time. In the long-run, unnecessary economic fluctuations can reduce growth, for example by increasing the riskiness of investments. A highly volatile economic environment might also have a negative impact on the choice of education profiles and career paths. In short, by maintaining a stable macroeconomic environment, economic policy can thus contribute to economic growth and welfare (Otmar, 2005).

In the late 1960s the Keynesian view became increasingly challenged by Monetarism. The debate between Keynesians and monetarists often focused on the effectiveness of policy instruments, with monetarists arguing for the ineffectiveness of fiscal tools and Keynesians believing in the superiority of fiscal stabilization policy (Gramlich, 1971). In the context of this discussion, Milton Friedman addressed the question of whether and how much to stabilize at his 1967 Presidential Address to the American Economic Association. Concerned about the possibility that monetary policy actions may themselves be a source of economic instability, Friedman argued that macroeconomic stability is best achieved using an “unconditional” policy rule: his famous “k-percent” money growth rule.

While nowadays nobody seems to support the use of such rigid rules, Friedman’s basic underlying idea remains relevant. His view on stabilization policy was grounded in the firm belief that the economic system is eventually self-stabilizing whereas available knowledge about the economic system is too limited for effectively addressing short-run fluctuations.

Even if one would subscribe to Friedman’s view of an eventually self-stabilizing economy, the question of whether reliance on self-stabilizing forces alone generates economic fluctuations of politically and economically acceptable magnitudes remains open. From a purely economic viewpoint, the optimal degree of stabilization depends on whether observed macroeconomic fluctuations constitute efficient responses of the economy to shocks or whether these fluctuations are partly due to economic frictions, to be addressed with the tools of stabilization policy. However, from a political economy viewpoint, self-stabilization may lead to short-term fluctuations of an intolerable size and even seriously undermine agents’ trust in a market-based economic system, as several historical episodes have shown.

In an article published by Lucas (2003) confirmed his long-held view that the welfare gains from stabilization policy must be fairly modest. According to his findings, the potential welfare gains from improved stabilization policy going beyond stability of monetary aggregates and nominal spending is likely to be small. While this result rests on important simplifying assumptions, it seems to have proven to be a fairly robust finding.

In recent times the overall stabilization problem has become much less severe. In particular, economic volatility – measured by the standard deviation of quarterly output growth – seems to have fallen considerably in many industrialized countries when comparing the recent two decades to the preceding post World War II experience. Some economists, including David and Christina Romer, suggested this to be due to a fundamental change in the understanding among policymakers about what aggregate demand policy can accomplish. This possibly validates the view that, in the past, severe recessions have been partly caused by over-ambitious macroeconomic policies (Romer & Romer, 2002). Whether this optimistic view about the source of business cycles is the final word on the issue remains to be seen. Clearly other views have been expressed, including the one that the recent experience is simply due to a fortunate sequence of extraordinarily small economic shocks (Blanchard. & Simon, 2001). Whatever viewpoint will ultimately turn out to be correct, they both request discussing the role of monetary and fiscal stabilization policies, be it to educate our minds and to avoid the mistakes of the past, or be it for effectively counteracting larger disturbances should these reappear.

Economists have expressed divergent views as to the roles of fiscal and monetary policies in the stabilization process of an economy. Stabilization of an economy involves the avoidance of large swings in economic activity, high inflation rates, excessive volatility in exchange and interest rates. Some regard monetary policy conducted by an independent and credible central bank as a predominant stabilization tool for most economies. Others opined that fiscal policy plays an important stabilization role in the economy if it is well coordinated with monetary policy. Some economists are however, of the view that no matter how independent a central bank is, its conduct of monetary policy may not be sufficient in determining the price level and that fiscal policy has a role to play. In this regard, as both fiscal and monetary policies are used to achieve set objectives, concerted efforts must be made to use them in a mutually reinforcing manner.

Empirical evidence suggests that countries whose policies are not coordinated may suffer from high deficits and inflationary pressures. This is because fiscal authorities for instance, in an election year will be reluctant to decrease spending and hence, accentuate inflationary pressures. Monetary authorities, on the other hand, have harsher stance on deficit and inflation (Bartolomeo & Gioacchino, 2008). Therefore, close coordination of fiscal and monetary policies is beneficial in order to effectively achieve the overall macroeconomic policy objectives of the respective authorities.

2.7. Monetary Policy Role

In general, stabilization policies can be implemented with the aid of either monetary or fiscal policy. As to the role of monetary stabilization policy, let us use the euro area as an illustration.

In the euro area the Maastricht Treaty assigns to monetary policy the responsibility for maintaining price stability. The clear assignment of price stability as the overriding objective of the European Central Bank – specified by a quantitative definition – provides guidance to economic agents as to what can be expected from monetary policy. Without doubt this enhances the credibility of monetary policy, contributing to the anchoring of medium and long-term inflation expectations in the euro area.

Stable inflation expectations eliminate an important source of macroeconomic instability, namely the possibility that economic shocks affecting inflation in the short-term become amplified via a corresponding adjustment in inflation expectations. In turn, the stability of these expectations contributes to economic welfare via a reduction of inflation risk premium contained, for example in nominal bond yields. By insuring price stability, monetary policy can thus make an important contribution to macroeconomic stability.

In its monetary policy strategy the Eurosystem has adopted a medium-term orientation. The forward-looking nature of this strategy insures that timely action is taken to address any potential threats to price stability. Yet, the medium-term orientation also reflects the existence of economic shocks, the consequences of which monetary policy cannot control without inducing excessively high variability in real activity and interest rates. A medium-term orientation should effectively guarantee that monetary policy itself does not become a source of economic fluctuations: it avoids misguided reactions to short-term developments, providing a safety net against overly ambitious economic fine-tuning. As is well-known, monetary history is full of examples where monetary policy activism – concerned too much with the short run – led to a sequence of decisions which had to be reversed within short periods of time. Such a policy is a source of instability and generates results opposite to the ones initially envisaged.

Overall, the medium-term orientation of monetary policy – guided by the objective of price stability – helps policy concentrating on the relevant economic shocks, that is on shocks and economic developments that monetary policy can effectively address. The focus on the medium-term may in a certain sense be interpreted as a practicable and economically reasonable compromise between Friedman’s idea on economic self-stabilization, which focuses entirely on the long-run, and the Keynesian view on economic fine-tuning, focused on shorter-term developments.

2.8. Fiscal Policy Role

Fiscal policy can promote macroeconomic stability by sustaining aggregate demand and private sector incomes during an economic downturn and by moderating economic activity during periods of strong growth.

An important stabilizing function of fiscal policy operates through the so-called “automatic fiscal stabilizers”. These work through the impact of economic fluctuations on the government budget and do not require any short-term decisions by policy makers. The size of tax collections and transfer payments, for example, are directly linked to the cyclical position of the economy and adjust in a way that helps stabilizing aggregate demand and private sector incomes. Automatic stabilizers have a number of desirable features. First, they respond in a timely and foreseeable manner. This helps economic agents to form correct expectations and enhances their confidence. Second, they react with an intensity that is adapted to the size of the deviation of economic conditions from what was expected when budget plans were approved. Third, automatic stabilizers operate symmetrically over the economic cycle, moderating overheating in periods of booms and supporting economic activity during economic downturns without affecting the underlying soundness of budgetary positions, as long as fluctuations remain balanced.

In principle, stabilization can also result from discretionary fiscal policy-making, whereby governments actively decide to adjust spending or taxes in response to changes in economic activity. We shall argue, however, that discretionary fiscal policies are not normally suitable for demand management, as past attempts to manage aggregate demand through discretionary fiscal measures have often demonstrated. First, discretionary policies can undermine the healthiness of budgetary positions, as governments find it easier to decrease taxes and to increase spending in times of low growth than doing the opposite during economic upturns. This induces a tendency for continuous increases in public debt and the tax burden. In turn, this may have adverse effects on the economy’s long-run growth prospects as high taxes reduce the incentives to work, invest and innovate. Second, many of the desirable features of automatic stabilizers are almost impossible to replicate by discretionary reactions of policy makers. For instance, tax changes must usually be adopted by Parliament and their implementation typically follows the timing of budget-setting processes with a lag. Not surprisingly, therefore, discretionary fiscal policies aiming at aggregate demand management have tended to be pro-cyclical in the past, often becoming effective after cyclical conditions have already reversed, thereby exacerbating macroeconomic fluctuations.

2.9. Empirical Review

The relative impact of fiscal and monetary policy has been studied extensively in many literatures. However, the bulk of theoretical and empirical research has not reached a conclusion concerning the relative power of fiscal and monetary policy to affect economic growth. Some researchers find support for the monetarist view, which suggests that monetary policy generally has a greater impact on economic growth and dominates fiscal policy in terms of its impact on investment and growth (Batten & Hafer, 1983; Elliot, 2009) while others argued that fiscal policy stimulant are crucial for economic growth (Olaloye & Ikhide, 1995).

Bokreta and Benanaya (2016) examined the relative impacts of fiscal and monetary policy on the economic growth of Algeria using the econometric modelling techniques of co-integration test and vector error correction mechanism to analyse the collected data from 1970 to 2014. From the estimation, government expenditure was positive while tax was negative; inflation exerted minimal impact while exchange rate was significant on economic growth, respectively. As such, fiscal policy established more powerful impact than the monetary policy towards accelerating the pace of sustainable economic growth.

Praise and Jacob (2018) investigated the impact of fiscal and monetary policy on the economic growth of 47 Sub-Saharan African countries covering the period of 1996 to 2016. A dynamic panel GMM technique and the Dumitrescu-Hurlin causality analysis were employed for the estimation. Findings indicated the existence of positive relationship between fiscal, monetary policy and economic growth across the examined countries. Further evidence showed that fiscal policy has larger and greater impact towards accelerating rapid economic growth than the monetary policy in Sub-Saharan Africa.

Noman and Khudri (2015) studied the impact of fiscal and monetary policies on economic growth in Bangladesh. The data were collected on annual scale from the period of 1979-80 to 2012-13. The study employed line diagram, correlation matrix, multiple linear regression models and trend analysis on fiscal (like, government revenue and expenditure) and monetary variables (like, exchange rate, interest rate, inflation, broad money, and narrow money). The major objectives of this study were to evaluate the trends in policy variables and examine the impact of fiscal and monetary instruments on economic growth (RGDP). The study also attempted to make recommendations based on the research findings. In accordance with the findings, narrow money, broad money, exchange rate, government revenue and expenditure had positive correlation with RGDP indicating that the unit increase in the above mentioned variables will lead to the unit increase in RGDP. On the contrary, inflation rate and interest rate on deposit had negative impact on RGDP. The results further revealed that there had been fluctuation in the trend of interest rate and inflation rate throughout the observed period and a drastic fall has occurred in narrow money between year 1999-00 and 2001-02. The upward trends have been observed in broad money, exchange rate, government revenue and expenditure. The results also showed that more than 75% of the total variation of dependent variable of each model used in this study was explained by the explanatory variables of the given model. The study concluded that exchange rate, interest rate, inflation rate, government revenue and government expenditure were significant variables that affect economic growth in Bangladesh.

Montiel and Eduardo (2010) applied a five-variable VAR model (money, wages, exchange rate, income and prices) to examine sources of inflationary shocks in Argentina, Brazil and Israel. The findings indicate that exchange rate movements among other factors significantly explained inflation in the three countries. Other studies which have reached similar conclusions are Kamin (2010) for United States, Nnanna (2002) for Nigeria and Lu and Zhang (2003) for China.

Syed, Jehseen, and Imtiaz (2010) investigated the comparative effect of fiscal and monetary policy on economic growth of Pakistan using ARDL approach to co-integration. The co-integration result suggests that both monetary and fiscal policy have significant and positive effect on economic growth. The coefficient of monetary policy is much greater than fiscal policy which implies that monetary policy has more concerned with economic growth than fiscal policy in Pakistan. The implication of the study is that the policy makers should focus more on monetary policy than fiscal to enhance economic growth. The role of fiscal policy can be more effective for enhancing economic growth by eliminating corruption, leakages of resources and inappropriate use of resources. However, the combination and harmonization of both monetary and fiscal policy are highly recommended.

In Nigeria, there have been very few empirical studies regarding the relative efficacy of the stabilization tools. In Nigeria, there have been very few empirical studies regarding the relative efficacy of the stabilization tools. Godwin (2010); Okpara (2011) in his study on money supply, government expenditure and prices in Nigeria, found a very poor and insignificant relationship between government expenditure and prices. Olubusoye. and Oyaromade (2008) analyzing the source of fluctuations in inflation in Nigeria using the frame work of error correction mechanism found that the lagged consumer price index (CPI) among other variables propagate the dynamics of inflationary process in Nigeria. The level of output was found to be insignificant but the lagged value of money supply was found to be negative and significant only at the 10% level in the parsimonious error correction model.

Idris (2019) investigated the relative impact of monetary and fiscal policy on output growth in a small-open economy. Specifically, the study examined the monetary and fiscal policy of the Nigerian economy over the period of 1980 to 2017 using annual time series data as well as evaluates the growing trend in critical indicators with the view to determining the existence of possible relationship. Using the OLS technique and the co-integration test, results indicated that both monetary and fiscal policy had positive and significant impact on economic growth. Furthermore, result showed that monetary policy was more effective in Nigeria than fiscal policy for the period under consideration. As such, there was need to impose fiscal discipline in the public finance since monetary policy cannot attain the desired goal given the existence of fiscal imbalances. The public sector should safeguard the maintenance of a steady macroeconomic environment which ensures that monetary aggregates are operating within the growth limits.

Adegoriola (2018) examined the effectiveness of monetary and fiscal policy instruments in stabilizing the Nigerian economy covering the period of 1981 to 2015 using data annual collected from documentary archives. By employing the Johansen co-integration and the error correction model, findings indicated the existence of positive relationship between money supply, government expenditure and revenue while interest rate and budget deficit have negative relationship with economic growth within the study period. As such, fiscal policy is more effective than the monetary policy.

Falade and Folorunso (2015) examined the relative effectiveness of fiscal and monetary policy instruments on economic growth sustainability in Nigeria in order to determine the appropriate mix of both policies. The paper employed error correction mechanism whereby the time series properties of fiscal and monetary variables were first examined using Augmented Dickey-Fuller and Philip Perron unit root tests, followed by Johansen co-integration test among the series using annual data for the period 1970-2013. The unit root test results revealed that all fiscal and monetary policy variables were non-stationary at first difference. The result showed that all the fiscal and monetary variables of interest co-integrated with the economic growth series in the country. This suggests that there was a long run relationship among fiscal and monetary variables and economic growth. The paper, however, found that the current level of exchange rate and its immediate past level, domestic interest rate, current level of government revenue and current level of money supply were the appropriate policy instrument mix in promoting economic growth both in the short and long run.

Ehikioya, Uduh, and Edeme (2018) investigated the impact of fiscal and monetary policies on the growth of SMEs in Nigeria using time series data covering the sample period of 1986 to 2015 by utilizing on the OLS estimation method. Results from the estimated coefficients indicated that fiscal policy was more effective and efficient than the monetary policy in encouraging the output growth performance of SMEs in Nigeria for the period under review. Musa, Asare, and Gulumbe (2013) examined the effectiveness of monetary and fiscal policies interaction on price and output growth in Nigeria the co-integration test and the VAR model based on the dynamic response of IRF and VD. By utilizing a time series data covering 1970 to 2010, result indicated that both monetary and fiscal policy had a significant impact on economic growth, but the fiscal policy appeared more relevant for sustainable growth.

Uzoamaka, Emmanuel, and Awa (2019) evaluated the effect of fiscal and monetary policy instruments on economic growth of Nigeria from 1985-2016. The data collected were analyzed using descriptive statistics such as Mean, Standard Deviation and Skewness and the relationship between the variables of the model was tested using Autoregressive Distributed Lag Model (ARDL) regression analysis after the data was found to be stationary and integrated of different orders. The result of the ARDL regression analysis showed that monetary policy rate had a positive relationship with real gross domestic product which was unexpected owing to its ultimate effect on prime lending rate which affects productive economic activities. Government recurrent expenditure was found to have positive significant relationship with economic growth. Accordingly, the long run relationship between monetary policy, fiscal policy instruments and economic growth in Nigeria points to the critical role of the monetary policy decision of the Central Bank of Nigeria and Federal Government fiscal policy programmes on growth and development of economy.

The study concluded that monetary policy measured by monetary policy rate and the fiscal policies proxied by government recurrent expenditure had not significantly affected economic growth in Nigeria. It was recommended that the Central Bank of Nigeria should further develop the financial sector through making more funds available to the private sector by reducing monetary policy rate which affects interest rate ceiling on loans to the private sector. And that the Central Bank of Nigeria should further develop the financial sector through making more funds available to the private sector by reducing monetary policy rate which affects interest rate ceiling on loans to the private sector.

Ogar, Nkamare, and Emori (2014) study, examined the empirical link on the effect of fiscal and monetary policy on the economic growth of Nigeria (1986-2010). The objectives were to determine factors of fiscal and monetary policy that contributed to the growth of Nigeria economy. It made use of secondary data, from Central Bank of Nigeria statistical Bulletin, and employed the ordinary least squares method of statistical analysis. It was found that, government revenue had a positive impact and statistical significant on gross domestic product. Also shown that, government expenditure was positively significant on the growth of Nigeria economy. The second model depicts that money supply had a positive impact on gross domestic product and it discovered that this variable was statistically significant. Exchange rate variable had a positive impact on the performance of Nigeria economy. The finding revealed that inflation had a positive impact but there was no significant relationship between inflation and gross domestic product. It therefore suggested that government should increase the number of fiscal policy instruments over and above the ones currently in use. The study recommended that measures should be adopted that would ensure income generation and government revenue generating ventures.

Omoka and Ugwuanyi (2010) in their long run study of money, price and output in Nigeria found no co-integrating vector but however found that money supply granger causes both output and inflation suggesting that monetary stability can contribute towards price stability. Also, Olukayode (2009) in his study of government expenditure and economic growth found that private and public investments have insignificant effects on economic growth during the review period 1977-2006. Ajisafe and Folorunso (2002) in their analysis, showed that monetary rather than fiscal policy exerts a great impact on economic activity in Nigeria using co-integration and error correction modeling techniques. The emphasis on fiscal action of the government has led to greater distortion in the Nigerian economy.

Medee and Nenbee (2011) investigated the impact of fiscal policy variables on economic growth in Nigeria and the result showed that, there exists a mild long-run equilibrium relationship between economic growth and fiscal policy variables. The response of the gross domestic product to one standard innovation in government expenditure implies that government expenditure has not impacted significantly on the economic growth but raising capital inflow will increase economic growth. Amassoma, Nwosa, and Olaiya (2011) examined the effect of monetary policy on macroeconomic variables in Nigeria for the period 1986 to 2009 by adopting a simplified Ordinary Least Squared technique and found that the monetary policy had a significant effect on exchange rate and money supply while monetary policy was observed to have an insignificant influence on price instability.

Effiong, Igbeng, and Tapang (2012) however, investigated accounting implications of fiscal and monetary policies on the development of the Nigerian stock market. It was discovered that only a mixture of monetary and fiscal policy exerted a significant impact on the development of Nigerian stock market. Also, Enahoro, Jayeola, and Onou (2013) reported that fiscal and monetary policies had enhanced operational efficiency in the Nigerian financial institutions, by reducing financial indiscipline in the financial and fiscal systems. The paper concluded that fiscal and monetary policies had galvanized government to commit budgetary management which would also address anomalies in the financial system. Ogege and Shiro (2012) however, investigated the dynamics of Nigeria’s monetary and fiscal policies, focusing specifically on their effects on the growth of Nigerian economy. The study revealed that both monetary and fiscal policy contributed to the growth of Nigerian economy. Similarly, Sanni, Amusa, and Agbeyangi (2012) found that none of the policies can be said to be superior to another and that a proper mix of the policies may enhance a better economic growth.

Ajisafe and Folorunso (2002) in their analysis, showed that monetary rather than fiscal policy exerts a great impact on economic activity in Nigeria using co-integration and error correction modeling techniques. The emphasis on fiscal action of the government has led to greater distortion in the Nigerian economy. The Error Correction Mechanism and Co-integration technique was employed by Adefeso and Mobolaji (2010) to estimate the relative effectiveness of fiscal and monetary policy on economic growth in Nigeria using annual data from 1970-2007. The empirical result showed that the effect of monetary policy is stronger than fiscal policy and the exclusion of the degree of openness did not weak this conclusion.

3. Research Methodology and Model Specification

This study investigates the relationship between monetary-fiscal policy mix and economic stabilization in Nigeria from 1986-2017 through the application of Johansen Co-integration technique and complemented with vector error correction model (VECM) to analyze the impact of the variables. The methodology involves estimating an econometric model in which the link between monetary – fiscal policy mix and economic stabilization in Nigeria is investigated. The co-integration method is used to accommodate deviations in its estimation because in time series analysis, variables often deviate from their mean paths because of various shocks and cyclic fluctuations. And thus, results between two-time series variables might be spurious. VECM is used to capture the dynamics of the postulated relationship. The unit root test which is a pretest of co-integration will be employed in order to validate the stationarity of the variables. Time series data are often assumed to be non-stationary and thus it is necessary to perform a pre-test to ensure that there is a stationary co-integrating relationship among the variables to avoid the problem of spurious regression.

Unit Root Test: The first step involves testing the order of integration of the individual series under consideration. Researchers have developed several procedures for the test of order of integration. The most popular ones are Augmented Dickey-Fuller (ADF) test due to Dickey and Fuller (1981) and the Phillip Perron (PP) and Phillips and Perron (1988). Augmented Dickey-Fuller test relies on rejecting a null hypothesis of unit root (the series are non-stationary) in favour of the alternative hypotheses of stationarity. The tests are conducted with and without a deterministic trend (t) for each of the series. The general form of ADF test is estimated by the following equation:

Where:

Y is a time series, t is a linear time trend, ∆ is the first difference operator,  is a constant, n is the optimum number of lags in the dependent variable and

is a constant, n is the optimum number of lags in the dependent variable and  is the random error term; the difference between Equation 1 and Equation 2 is that the first equation included just a drift. However, the second equation includes both drift and linear time trend.

is the random error term; the difference between Equation 1 and Equation 2 is that the first equation included just a drift. However, the second equation includes both drift and linear time trend.

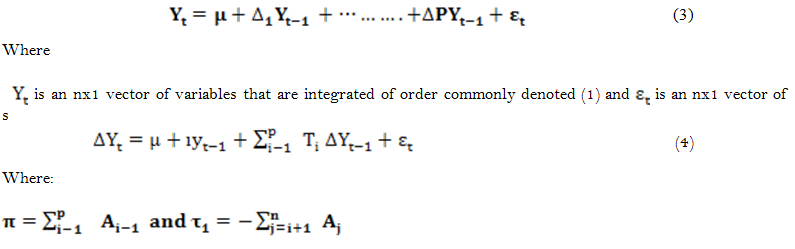

Co-Integration: The second step in this time series analysis is to test for the presence or otherwise of co-integration between the series of same order of integration through forming a co-integration equation. The basic idea behind co-integration is that if in the long-run, two or more series move closely together, even though the series themselves are trended, the difference between them is constant. It is possible to regard these series as defining a long-run equilibrium relationship, as the difference between them is stationary (Hall & Henry, 1989). A lack of co-integration suggests that such variables have no long-run relationship: in principle they can wander arbitrarily far away from each other. We employ the maximum-likelihood test procedure established by Johansen. and Juselius (1990) and Johansen (1991). Specifically, if  is a vector of n stochastic variables, then there exists a p-lag vector auto regression with Gaussian errors of the following form: Johansen’s methodology takes its starting point in the Vector Autoregression (VAR) of order P given by:

is a vector of n stochastic variables, then there exists a p-lag vector auto regression with Gaussian errors of the following form: Johansen’s methodology takes its starting point in the Vector Autoregression (VAR) of order P given by:

To determine the number of co-integration vectors, Johansen (1988) and Johansen. and Juselius (1990) suggested two statistic test, the first one is the trace test (λ trace). It tests the null hypothesis that the number of distinct co-integrating vector is less than or equal to q against a general unrestricted alternatives q = r; the test calculated as follows:

Where T is the number of usable observations, and the the estimated eigenvalue from the matrix.

the estimated eigenvalue from the matrix.

3.1. Model Specification

Specifically, the equation for estimation is of the following functional form:

GDP= f (M2, LIR, GRE, GEX, INF) (5)

Equation 5 can be transformed into an econometric model as follows:

A priori Expectations:

Using the co-integration method, this study aims to examine the empirical relationship between monetary - fiscal policy mix and economic stabilization in Nigeria. The variables used in this study are: Gross domestic product (GDP) represents economic growth, Money supply (M2), Lending interest rate (LIR), Government revenue (GRE), Government expenditure (GEX) and Inflation (INF).

4. Analyses of Estimated Results

Table-1. Descriptive Statistics of the variables.

| |

GDP |

M2 |

LIR |

GRE |

GEX |

INF |

| Mean |

18463591 |

5247796. |

22.95813 |

4179910. |

3618899. |

19.07188 |

| Median |

5818734. |

1388747. |

22.69500 |

2068880. |

1018091. |

11.50000 |

| Maximum |

71857270 |

19823476 |

36.09000 |

12904729 |

60820594 |

72.80000 |

| Minimum |

69146.99 |

23806.40 |

12.00000 |

16223.70 |

12595.80 |

5.400000 |

| Std. Dev. |

23620664 |

6898857. |

4.491251 |

4552622. |

10604346 |

17.38431 |

| Skewness |

1.255467 |

1.075122 |

0.575150 |

0.724862 |

5.126669 |

1.743029 |

| Kurtosis |

3.271311 |

2.612917 |

4.495141 |

2.009993 |

28.19782 |

4.934950 |

| Jarque-Bera |

8.504528 |

6.364514 |

4.744852 |

4.109082 |

986.7479 |

21.19551 |

| Probability |

0.014232 |

0.041492 |

0.093254 |

0.128152 |

0.000000 |

0.000025 |

| Sum |

5.91E+08 |

1.68E+08 |

734.6600 |

1.34E+08 |

1.16E+08 |

610.3000 |

| Sum Sq. Dev. |

1.73E+16 |

1.48E+15 |

625.3115 |

6.43E+14 |

3.49E+15 |

9368.645 |

| Observations |

32 |

32 |

32 |

32 |

32 |

32 |

We note from Table 1 above that the mean of the dependent variable, GDP is 1846. The means of the independent variables, Money supply (M2), Lending interest rate (LIR), Government revenue (GRE), Government expenditure (GEX) and Inflation rate (INF) are 5248, 22.93, 4180, 3619 and 19.07 respectively. The standard deviation (Std. Dev.) tells us that the variables are well spread out. That is to say that the degree of variability of the variables is good. This is evident from the high standard deviation values of 2362, 6899, 4.4913, 4553, 1060, and 17.3843 for the respective variables of GDP, M2, LIR, GRE, GEX and INF. This indicates that the data points are spread out over a large range of value. All the variables were positively skewed to the left with an extension to the right and with skewness coefficient of 1.255, 1.075, 0.575, 0.725, 5.127 and 1.743 for the respective variables. This distribution is highly skewed. With a skewness value of 5.127, GEX showed a more symmetric distribution than the other variables in the model. Also, all the data showed positive kurtosis (Leptokurtic). GEX showed the highest peak of 28.198 while GRE of 2.010 showed the flattest. This indicates that the distribution has heavier tails and a sharper peak than the normal distribution. The Jarque-Bera statistic revealed that LIR and GRE are normally distributed while the other variables were not. This is evident from their probabilities which approximate zero.

4.1. Co-Integration Results

The results of the unit root test indicate that all the variables in the model were stationary at the 5% level after first differencing. Thus, using them is not likely to lead to the problem of spurious regression. Therefore, we can go ahead to test for co-integration which shows the long run relationship between gross domestic product (GDP) and the monetary-fiscal policy mix.

Having verified that all empirical variables were stationary and integrated of the same order, the study tests for the existence of long run equilibrium relationship between the variables in the model. A vector of variables integrated of order one is integrated if there exists linear combination of the variables which are stationary. In this study, following the approach of Johansen. and Juselius (1990) two likelihood ratio test statistics, the trace and maximum Eigenvalue test statistics are utilized to determine the number of co-integrating vectors. The co-integration property requires all variables to converge in the long run. The test for this property is conducted and the results are shown in Tables 2 (a) and (b).

The procedure followed to determine the number of co-integrating vectors begins with the null hypothesis that there are no co-integrating vectors, HO. A rejection of the hypothesis can lead to testing the alternative hypothesis, HA. The testing procedure continues until the null hypothesis cannot be rejected any longer. Tables 2 (a) and (b): Results of Multivariate Johansen Co-integration Tests Tables 2 (a): Results of Unrestricted Co-integration Rank Test (Trace) Hypothesized No. of Co-integrating Equations (r).

Table-2.(a). Results of unrestricted co-integration rank test (Trace).

Hypothesized No. of Co-integrating Equations (r) |

Eigen value |

Trace test statistic K = 2 |

Prob.** |

Ho |

HA |

(λ trace) |

Critical Value (0.05) |

r  0 |

r > 0 |

0.904592 |

172.6768* |

95.75366 |

0.0000 |

r  1 |

r > 1 |

0.712730 |

102.1891* |

69.81889 |

0.0000 |

r  2 |

r > 2 |

0.510625 |

64.76915* |

47.85613 |

0.0006 |

r  3 |

r > 3 |

0.450815 |

43.33036* |

29.79707 |

0.0008 |

r  4 |

r > 4 |

0.435888 |

25.35076* |

15.49471 |

0.0012 |

r  5 |

r > 5 |

0.238544 |

8.175696* |

3.841466 |

0.0042 |

Note: Trace test indicates 6 co-integrating equation(s) at the 0.05 level

*denotes rejection of the hypothesis at the 0.05 (5%) level; r represents number of co-integrating vectors; k represents number of lags in the unrestricted VAR model **MacKinnon, Haug, and Michelis (1999) P-values. |

Table-2(b). Results of unrestricted co-integration rank test.

| (Maximum Eigenvalue) |

Hypothesized No. of Co-integrating Equations (r) |

Eigen value |

Max-Eigen Statistic K = 2 |

Prob.** |

Ho |

HA |

(λ Max) |

Critical Value (0.05) |

r = 0 |

r = 1 |

0.904592 |

70.48767* |

40.07757 |

0.0000 |

r = 1 |

r = 2 |

0.712730 |

37.41997* |

33.87687 |

0.0181 |

r = 2 |

r = 3 |

0.510625 |

21.43879 |

27.58434 |

0.2506 |

r = 3 |

r = 4 |

0.450815 |

17.97960 |

21.13162 |

0.1306 |

r = 4 |

r = 5 |

0.435888 |

17.17506* |

14.26460 |

0.0169 |

r =5 |

R=6 |

0.238544 |

8.175696* |

3.841466 |

0.0042 |

Note: Max-Eigenvalue statistic indicates 4 co-integrating equation(s) at the 0.05 level; *denotes rejection of the hypothesis at the 0.05 (5%) level; r represents number of co-integrating vectors; k represents number of lags in the unrestricted VAR model. **MacKinnon, Haug, and Michelis (1999) P-values. |

The results based on co-integration technique reveal that both the trace statistic and maximum Eigenvalue statistic confirm the existence of co-integrating equations among the variables of interest. It is evident that the trace test indicates six co-integrating equations while maximum Eigenvalue test reveals four co-integrating equations in the model, as the null hypothesis of no co-integration (r = 0) is rejected. Since the variables are co-integrated, this satisfies the convergence property. Although, when the results obtained from the trace statistic and maximum Eigenvalue statistic yield different conclusions, the trace statistic is preferred. This is supported by Cheung and Lai (1993) who found that the trace statistic showed more robustness to both skewness and excess kurtosis in the residuals than the maximum Eigenvalue test statistic. Fortunately, the results of test statistics with the selected lag lengths indicate that there was more than one co-integrating relationship between gross domestic product (GDP) and monetary-fiscal policy mix variables at the five percent (5%) level of significance. These results suggest that there is a unique long run equilibrium relationship among the variables of interest. This result is similar to that of Agbonkhese and Agbonkhese (2017) who investigated foreign direct investment (FDI) and Nigeria’s growth using similar variables as well as the same technique to achieve the objective of the study.

4.2. VECM Results

The estimation of a VECM requires not only for the variables to be linked in the short run, but also to be related in the long run via the existence of co-integration which has been fully satisfied. This estimation is to show the robustness of the long run relationship established by co-integration. The result is shown in Table 3.

The estimated Vector Error Correction Model (VECM) helps us to evaluate the short run behaviour and the adjustment to the long run model. Error Correction Term or model (ECT or ECM) from the one co-integrating relation is included to capture the speed of adjustment to a disturbance in the long run equilibrium in respective vectors. The results of the VECM are presented in Table 3 above. Here the short run dynamics for Nigeria are estimated using the error correction representation of the model that include two lags for each of the first differences for the six variables and the equilibrium error correction terms. Error correction coefficient can be treated as a mechanism, which ties the short run behaviour to its long run value. It simply shows the speed with which the system converges to equilibrium. If it is statistically significant it shows what proportion of the disequilibrium in dependent variable in one period is corrected in the next period. From Table 3, the error correction coefficient (-0.0498) which measures the speed of adjustment towards long run equilibrium has the required negative sign, lies within the accepted region of less than unity and significant at 10% level. The coefficient of Vector Error Correction (VEC) indicates a speed of about 4.98% of the previous period disequilibrium from the long run economic growth. This also implies that the speed with which the variables (M2, LIR, GRE, GEX, and INF) adjust from short-run disequilibrium to changes in economic growth (GDP) in order to attain long run equilibrium is 4.98% within one period. The coefficient also suggests that the speed of adjustment towards equilibrium is quite reasonable.

The error correction estimate of -0.1109 for M2 indicates that 11.09% of the preceding period’s disequilibrium is eliminated in the current period, with immediate adjustments captured by the difference terms. The LIR, GRE, GEX, and INF indicate 1.90%, 5.92%, 360.37%, and 1.25% respectively, of the preceding periods’ disequilibrium that is eliminated in the current period. In the result for lagged economic growth (GDP), all the variables have positive relationships with GDP except lending interest rate (LIR) and government expenditure (GEX) in lag 1 while in lag 2 all the variables have negative relationships with GDP except money supply (M2) and inflation (INF). Furthermore, all these variables are significant to themselves at different levels in both lags. For instance, GDP is significant to itself at 10% in lag 1 and 5% in lag 2. M2 is not significant at both lags while LIR is significant in lag 2 at 10% and not significant in lag 1. GRE is not significant in both lags while GEX is significant in lag 1 at 10% and not significant in lag 2. INF is significant in all the lags.

Table-3. Vector error correction model (VECM) Results.

| Variable |

D (GDP) |

D (M2) |

D (LIR) |

D (GRE) |

D (GEX) |

D (INF) |

| ECT/ECM |

-0.0498 |

-0.1109 |

1.9008 |

-0.0592 |

3.6037 |

-1.2507 |

| |

(0.3595) |

(0.0697) |

(4.7107) |

(0.0824) |

(0.2217) |

(1.2106) |

| |

[-1.3862]* |

[-1.5914]* |

[ 0.0404] |

[-0.7182] |

[16.2545]*** |

[-0.1014] |

| D(GDP(-1)) |

0.7187 |

0.1366 |

-4.9007 |

0.3605 |

-2.9499 |

6.7607 |

| |

(0.5122) |

(0.0993) |

(6.7407) |

(0.1174) |

(0.3158) |

(1.8406) |

| |

[ 1.4032]* |

[ 1.3760]* |

[-0.7294] |

[ 3.0665]*** |

[-9.3398]*** |

[ 0.3859] |

| D(GDP(-2)) |

-1.4170 |

0.0013 |

-3.1807 |

-0.0536 |

-3.2401 |

1.3107 |

| |

(0.5891) |

(0.1142) |

(7.7207) |

(0.1350) |

(0.3632) |

(2.0706) |

| |

[-2.4056]** |

[ 0.0115] |

[-0.4120] |

[-0.3971] |

[-8.9203]*** |

[ 0.0652] |

| D(M2(-1)) |

-5.0407 |

-0.4613 |

3.5806 |

-2.2340 |

4.7451 |

-3.7206 |

| |

(2.6264) |

(0.5091) |

(3.4706) |

(0.6020) |

(1.6195) |

(9.0806) |

| |

[-1.9192]** |

[-0.9061] |

[ 1.0403] |

[-3.7107]*** |

[ 2.9300]*** |

[-0.4142] |

| D(M2 (-2)) |

9.9468 |

0.6924 |

1.7206 |

0.9371 |

6.3406 |

-1.2506 |

| |

(2.8935) |

(0.5609) |

(3.8106) |

(0.6633) |

(1.7842) |

(9.9306) |

| |

[ 3.4376]*** |

[ 1.2345] |

[ 0.4530] |

[ 1.4129]* |

[ 3.5538]*** |

[-0.1264] |

| D(LIR(-1)) |

-68084.37 |

-10228.55 |

-0.2774 |

-30347.12 |

50668.34 |

-0.1494 |

| |

(171116.) |

(33168.9) |

(0.2243) |

(39223.9) |

(105514.) |

(0.5848) |

| |

[-0.3979] |

[-0.3084] |

[-1.2368] |

[-0.7737] |

[ 0.4802] |

[-0.2555] |

| D(LIR(-2)) |

65645.07 |

-777.4092 |

-0.3360 |

34139.31 |

185560.3 |

1.5134 |

| |

(169371.) |

(32830.6) |

(0.2220) |

(38823.9) |

(104438.) |

(0.5789) |

| |

[ 0.3876] |

[-0.0237] |

[-1.5136]* |

[ 0.8793] |

[ 1.7768]** |

[ 2.6145]*** |

| D(GRE(-1)) |

1.4611 |

-0.0504 |

6.5407 |

-0.4158 |

6.4220 |

-1.5206 |

| |

(1.4778) |

(0.2865) |

(1.9806) |

(0.3388) |

(0.9113) |

(5.1806) |

| |

[ 0.9887] |

[-0.1758] |

[ 0.3377] |

[-1.2274] |

[ 7.0474]*** |

[-0.3018] |

| D(GRE(-2)) |

2.4579 |

0.1796 |

-3.7007 |

0.2209 |

4.1106 |

1.9006 |

| |

(1.0931) |

(0.2119) |

(1.4006) |

(0.2506) |

(0.6740) |

(3.7406) |

| |

[ 2.2485]** |

[ 0.8477] |

[-0.2583] |

[ 0.8814] |

[ 6.0984]*** |

[ 0.5084] |

| D(GEX(-1)) |

1.8426 |

1.5912 |

-7.2706 |

3.1406 |

-6.1303 |

7.5106 |

| |

(7.1685) |

(1.3895) |

(9.4806) |

(1.6432) |

(4.4203) |

(2.4805) |

| |

[ 0.2570] |

[ 1.1451] |

[-0.7733] |

[ 1.9113]* |

[-1.3869]* |

[ 0.3066] |

| D(GEX(-2)) |

-7.9903 |

0.2920 |

-6.6406 |

0.8828 |

-4.4448 |

1.3205 |

| |

(5.9347) |

(1.1504) |

(7.8306) |

(1.3604) |

(3.6595) |

(2.0905) |

| |

[-1.3464]* |

[ 0.2538] |

[-0.8540] |

[ 0.6490] |

[-1.2146] |

[ 0.6489] |

| D(INF(-1)) |

-13541.82 |

-1267.973 |

0.0691 |

3780.873 |

-34919.48 |

0.2521 |

| |

(54474.0) |

(10559.2) |

(0.0714) |

(12486.8) |

(33589.9) |

(0.1862) |

| |

[-0.2486] |

[-0.1201] |

[ 0.9676] |

[ 0.3028] |

[-1.0396] |

[ 1.3543]* |

| D(INF(-2)) |

-8028.197 |

-1292.755 |

-0.0962 |

-4080.683 |

-48004.17 |

-0.4078 |

| |

(54433.8) |

(10551.4) |

(0.0714) |

(12477.5) |

(33565.1) |

(0.1860) |

| |

[-0.1475] |

[-0.1225] |

[-1.3477]* |

[-0.3270] |

[-1.4302]* |

[-2.1918]** |

| Constant (C)) |

504505.0 |

-208977.7 |

1.3767 |

-94396.79 |

7197032. |

-4.1288 |

| |

(1598043) |

(309762.) |

(2.0948) |

(366310.) |

(985387.) |

(5.4616) |

| |

[ 0.3157] |

[-0.6746] |

[ 0.6572] |

[-0.2577] |

[ 7.3038]*** |

[-0.7560] |

| R2 |

0.6126 |

0.6089 |

0.4408 |

0.6071 |

0.9702 |

0.4926 |

| Adj. R2 |

0.2768 |

0.2700 |

-0.0441 |

0.2665 |

0.9443 |

0.0529 |

| S.E. Equation |

3889202. |

753877.7 |

5.0982 |

891498.4 |

2398165. |

13.2920 |

| F- Statistic |

1.8244 |

1.7968 |

0.9091 |

1.7825 |

37.5372 |

1.1204 |

| AIC |

33.4916 |

30.2101 |

6.4019 |

30.5455 |

32.5246 |

8.3185 |

| Schwarz |

34.1517 |

30.8701 |

7.0620 |

31.2055 |

33.1847 |

8.9785 |

Note: Standard Errors are in parenthesis and t values are in brackets.

*/**/*** = Significant at 10%, 5% and 1% levels. |