Uprooted in Art: Contemporary Considerations of Refugee Art

Alan Garfield1

1Art Historian. Chair, Digital Art and Design Department University of Dubuque. Dubuque, Iowa USA. |

AbstractThe visual arts (like music and literature) have been immeasurably enriched by the contributions of artists from every land. In every nation, there is a unique story of cross-fertilization and cultural contributions by the immigrant imagination, coming from every direction of the globe. This paper will introduce historical and recent refugee art by examining imagery created by outcasts, usually in refugee camps which, by their political definition, are meant to have no history, no permanence and (like their residents), no future. These travellers, like their imagery, is meant to be forgotten. |

Licensed: |

|

Keywords: |

1. Introduction

The history of visual art, like music and literature, has been immeasurably enriched by the contributions of artists from every land. In every nation, there is a unique (but surprisingly similar) story of cross-fertilization and cultural contributions by the immigrant imagination, coming from every direction of the globe. But when we examine the refugee narrative in art, we find both the immigrant and those (we might call them empathic nationalists) who present quite a different message of the displaced. It’s most usually couched in politico-economic terms and, of course, linguistically confusing. In Canada, you find phrases like “newcomers and undocumented immigrants” while in the US, “migrant and immigrant” hold different legal weights. The use of these terms is equally unclear in public discussion. 1

How feisty has the fear of the refugee become in Western Europe and the United States. By its very nature in the press and media, every discussion of the immigrant, the refugee, the stranger is designed to be emotional and to frighten the masses. Most often, the emotion sought is one of fear-mongering. Yet sorrow and empathy also exist in this discussion. Fear has always been a barrier to culture for it is all too easy to mistake fear for actual danger.2 In the face of this notion of the stranger (someone so destructive and absurd), what role can art play? In fact, just what are some of the images the refugee creates?

This is clearly a thorny question since the imagery is usually created in refugee camps which, by their political definition, are meant to have no history, no permanence and (like their residents), no future. These travelers, like their imagery, is meant to be forgotten.

2. Methodology

Using historical and contemporary original sources, imagery of the disenfranchised - the refugee - will be examined within its historical context. The methodology will be to introduce this imagery within its context to a wider audience. Much of the imagery is intended not to be permanent and therefore will be, has been, destroyed. While using a methodology borne more closely to the humanities than social sciences (art history rather than sociology), it is the purpose of this paper to introduce and examine refugee imagery as metaphor of the displaced, specifically by viewing and analyzing a number of systemic works, starting historically with 19th century Bourbon France and continuing to the present (Bermel, 2007; Charteris-Black, 2009; Franke, 2000; Lakoff & Johnson, 1980; Wee, 2006).3

3. Discussion

Art is not politics, but clearly it is entangled into all of its aspects. It’s messy, embedded, troubled and irresistible. Yet art is not outside the politics of contemporary concerns with immigration. In fact, politics resides within its production, its distribution and its reception. The sets of circumstances involving immigration and refugee status are incredibly complicated. In the balance of the images introduced here, we experience hope as well as hate.

But hope turns quickly to anger or depression, as in this iconic image of 3 year-old Aylan Kurdi. The images of this toddler’s lifeless body on a Turkish beach have reverberated across the globe, stirring public outrage and embarrassing political leaders as far away as Canada, where authorities had rejected an asylum application from the boy’s relatives.

The child pictured face down in a red t-shirt and shorts was identified as a Syrian Kurd from Kobani, a war-torn Syrian town near the Turkish border that has witnessed years of heavy fighting between Islamic State and Syrian Kurdish forces. He drowned after the 15-foot boat ferrying him from the Turkish beach resort of Bodrum to the Greek island of Kos capsized shortly before dawn on Wednesday, September 2, 2015. He was among 12 passengers that died that morning including Galip, his 5-year-old brother, and Rehan, his mother. His father, Abdullah, was the only family member to survive. 4

Images of the displaced in the media are sobering, indeed. But it hasn’t always been that way. In print and social media, immigration and refugee camps in the 21st century are overcrowded, dangerous and depressive. 200 years before Aylan, French immigrants leaving Paris happened on a similar watery end, but the resultant message was hope in the midst of human death and destruction.

There's a compelling showbiz mythology involved any discussion of migrant motivation. According to this “new land” narrative, if the new venue doesn’t actually have streets paved in gold, then at least it’s better than where the refugees were coming from. We've seen it and we've loved it – in song, in literature, on stage and on screen. But we all know that the displaced are, at least initially, a noisy, potentially violent and alarmingly anonymous group. The solution, literally for early 19th century Paris, was to ship the rowdy dissidents back home.

That is the situation Paris found itself in after the 1810s. For his Salon picture in 1819, Théodore Géricault chose a dramatic episode — the wreck of the frigate Medusa, which had set off with a French fleet on an expedition to Senegal. Before we look at the painting, at 16’ x 24’ one of the largest in the Louvre, let us review the actual events which this painting is based upon.

On June 17, 1816, the new Bourbon government of France dispatched the frigates Medusa, Loire and Echo and the brig Argus to officially receive the British handover of the port of Saint-Louis in Senegal to France. The British who having helped to re-establish the French monarchy, wanted to demonstrate their support for Louis XVIII, and decided to hand over to him this strategic trading port on the West African coast. The French naval frigate, Medusa was to carry 365 crew and passengers, including the Senegal’s governor-designate, Colonel Julien-Désire Schmaltz, from Port de Rochefort on the island of Aix on France’s west coast, to Senegal via Tenerife.

The captain of the Medusa was Vicomte Hugues Duroy de Chaumereys, who at the age of 53 had spent most of his career behind a desk at customs offices and had not only never been a captain but he hadn’t been on a ship in decades. But his uncle was well-connected, and he was put in command of the Medusa. According to later interviews, the governor-designate Schmaltz wanted to reach St Louis as soon as possible and persuaded the captain to set a course close to the shore line in order to save time. Things went badly almost from the start of the voyage when a young cabin boy was lost over the side. Captain Chaumereys also had problems with both his passengers and crew, spending long periods arguing with them. There was another wrinkle in this ill-fated journey. The new Bourbon government made it clear that those not happy with ‘official’ France could secure their passage back home. Make no mistake, this act served three purposes: basic transport, a method to remove dissidents (mainly Africans) and a compassionate act of land exchange. 5

The Medusa was a fast vessel and in fact much faster than the other vessels in the group and soon pulled ahead of them. This was going to be a contributing factor in the forthcoming disaster and terrible loss of life. Whether due to poor navigation skills or lack of attention, on 2 July the Medusa, many miles off course, ran aground on the Arguin Banks (a series of sandbars which lie off the west coast of Mauritania). There were near perfect weather conditions and calm seas. Nonetheless, the sandbar ripped a hole in the hull of the Medusa and after surveying the damage it was deemed un-repairable. Couple this factor along with the threat of potential storms, the crew decided to abandon the vessel. The Medusa had some lifeboats but they would hold only 150 people. It was decided to construct a raft to house the rest. 6

The crew then set to work making a raft from parts of the Medusa’s decking and masts. When completed the raft measured 65 feet by 23 feet and was towed behind two of the ship’s lifeboats. In all, 150 people, including one woman, boarded the raft. Whether it was the weight or poor seamanship, the raft began to submerge, and it was decided to toss the food and water. Without water, the main foodstuff was barrels of rum. The lifeboats towing the raft set off from the crippled Medusa but the problematic weight of the raft must have been obvious early on. During the evening of the first night, the rope was cut between the lifeboats and the raft, four miles off the coast of Mauretania in shark infested waters.

By the second day, three of the passengers had committed suicide and the store of rum aboard the raft was broached with fights ensuing between drunken soldiers, civilians and officers. By the fourth day, only sixty people were alive, finding sustenance in eating the corpses.

On 11 July 1816, after 9 days adrift, the raft was rescued by the Argus. 7. Only 15 men were still alive; the others had been killed, eaten, ravaged by sharks or simply thrown overboard by their comrades. Some had died of starvation; some had thrown themselves into the sea in despair. The whole episode was a disaster, not only to those who sailed on the Medusa but morally and politically for the French government.

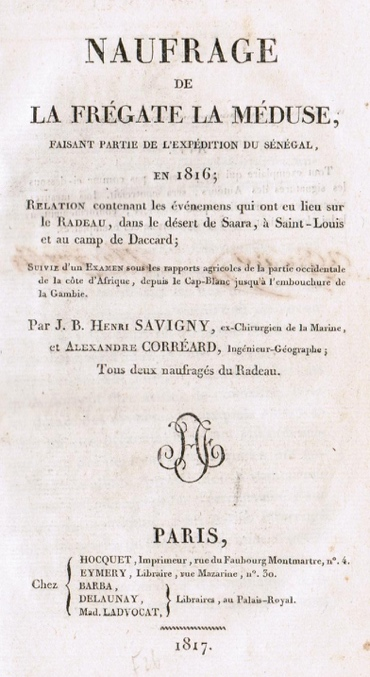

How did Gericault know of the story? He read the book. The ship’s surgeon, Savigny, had survived and he submitted a report to the government. It was leaked to the anti-government newspaper, the Journal des débats, and caused an outrage. The French government tried to suppress the details, which of course did not work, and thus made matters worse. The French nation was horrified. The event became an international scandal, partly because of the human disaster, partly because of the attempted cover-up and denial, and partly because the disaster was generally attributed to the incompetence of the French captain, whom people believed was acting under the authority of the recently restored French monarchy. 8 Captain de Chamereys was blamed for the incident and was court-martialed.

This painting was young Géricault’s first major work of art. Its size still overwhelms the viewer in the Louvre’s Grand Gallery. The artist took the popular formula for history painting and made a contemporary aesthetic news item out of it. It was a perfect storm and people were shocked. 9

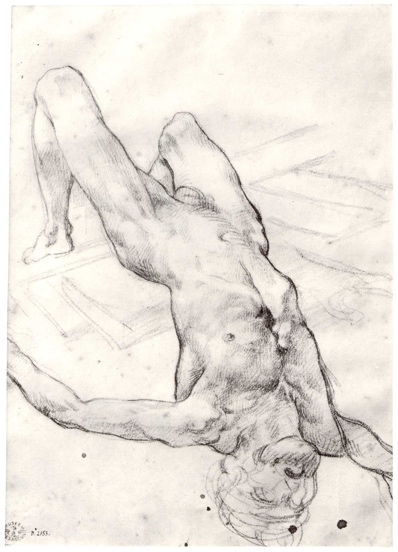

Géricault researched every aspect he could about the tragedy, creating numerous sketches and small studies. He interviewed the ship’s doctor, Henri Savigny and the ship’s geographer, Alexander Corréard. He created a detailed scale model of the raft in his studio above a barn. Models (friends and colleagues like the painter Delacroix) posed on the raft. Fellow painter Louis-Alexis Jamar modelled for the nude dead man in the foreground, bottom right, who is about to slip into the sea. In his desire to depict accurately the bodies of the survivors and the dead, he made many visits to morgues and hospitals noting details with regards the corpses.

When we stand in front of this painting (the one that launched the Romantic Movement), we can imagine the pain, smell the stench, and feel the grief of those refugee passengers. Gone from their homeland, we see them face near certain death in a most painful and dehumanized way. Géricault decided to focus on the silver lining of this narrative in the guise of the approaching ship, Argus, which can just be seen on the whitened horizon on the top right of the picture. These disenfranchised, in the midst of dire acceptance, now suddenly realize that they might yet become survivors. An African crewman, symbol of the outcast, can be seen standing on a cask waiving his shirt to attract the crew of the distant Argus. 10

This is 19th century VR at its best. The closeness of the bodies to the edge of the canvas, some complete and some ravaged, makes us almost believe we are just a step away from the raft itself. The raft has clearly suffered from the battering it endured in the so-called dramatic seas and is barely afloat (remember in fact they were calm seas). The painting is dark and somber, suggesting the torment and agony of the survivors. There is a moody darkness about the painting, but not defeatist. There is a strong diagonal surge from the bottom left of the painting to the top right. Our eyes move along the bottom left diagonal from viewing the despondent father, head in hand, holding his dead son, to the outcast black man waving his shirt in the upper right. As we stare in disbelief at the scene in front of us, we sympathize with the plight of these men.

It is an idealized painting, of course. These look like noble Roman wrestlers, not poor, half-starving, anti-Bourbon dissidents. And simply put, there are more people shown on the raft than were found by the Argus and at the time of the rescue on day 9. While the sea was reported as being calm and the weather settled, Gericault chose to heighten the emotion by creating a dangerous rolling sea. This is Gericault’s narrative of the outcast, an anti-establishment candidate, who survives (and will eventually prevail) in spite of the political reality. This is displaced man’s most heroic moment. Géricault must have been at least partially aware of the kind of reception this work was going to have. 11

3.1. Contemporary Images of the Displaced Refugee

Contemporary interpretations of the displaced recall a precarious life/death moment. Often, they are somber and uplifting, though not in that positive, heroic 19th century, traditional academic large-scale history-painting aesthetic way. While American media often shows large-scale immigration camps as examples of dangerous, dirty, inhumane living conditions where torture, terror and death are common, rarely do we see successful, positive refugee resolutions. This combination of fear, dehumanization and terror becomes a major theme for artists who both document and interpret scores of anonymous immigrant hardships and deaths. What we see are artists creating an alternative, if not slightly surreal, narrative of an event or events which have been willfully ignored or generally forgotten.

Death and its corollary, hope, is the theme of Patricia Ruiz-Bayón’s 2013 performance piece entitled 70+2… 12 The performance is part metaphor and part documentary. The 70+2… title commemorates the 2010 massacre of 72 migrants in the Matamoros area of NW Mexico (by the border town Brownsville). Mexican authorities call it the San Fernando Massacre, since it occurred in that southern section of Matamoros.

Mexican authorities say the ruthless murders of 72 undocumented immigrants from Central and South American were carried out by the Zetas criminal gang on August 23, 2010. Their bodies were found piled on top of each other in a mass shallow grave.

Ruiz-Bayón’s video performance piece is divided into three parts. In the first part, we see a dozen or so bystanders sitting and leaning against the walls of a large rectangular room which had fresh soil sprinkled on the floor. Inside this rectangular field, a path was prepared in the shape of an infinity symbol marked in red. On the red infinity path, 2 men and one woman, dressed in pure white, walk (one at a time) barefoot following the infinity symbol. In the second part, the barefoot walker sits down and has his/her feet washed slowly, silently and carefully. The audio background of both these sections features, a recording of a single flute playing a Pavane-like reflective piece to signal the somberness of the situation. In the third part of the video piece, actual interviews (in Spanish) are conducted with the relatives and friends of the murdered, thus breaking the psychical distance between ‘art’ and ‘life’, ‘us’ vs ‘them’.

In the video performance, the danger, the fear, the Christ-like sacrifice becomes a metaphor for the lives of these (and other) undocumented workers in the US. These 3 anonymous players become the symbolic 72. The infinity symbol visually becomes the eternal path of migration while each person’s simulated sacrifice and death in a mass grave evokes hope and renewal.

Ruiz-Bayón takes a specific incident and makes it universal, just as Gericault does. Her video performance series has continued with this theme in her series entitled Todos Somos Victimas y Culpables (We Are All Victims and Culpable).

3.2. Sarcasm in Images of Refugee Art

Rarely are we witness light-hearted imagery with the subject of the displaced. News reports focus on the travails of travel, from land to sea, from point A to point B. When the public witnesses the displaced, art is the last thing that is seen. Instead there are bodies, overturned ferries, layers of armed guards that makeup a virtual wall, enforced border security with bridges and electronic fences, or hundreds of miles of hard fencing.

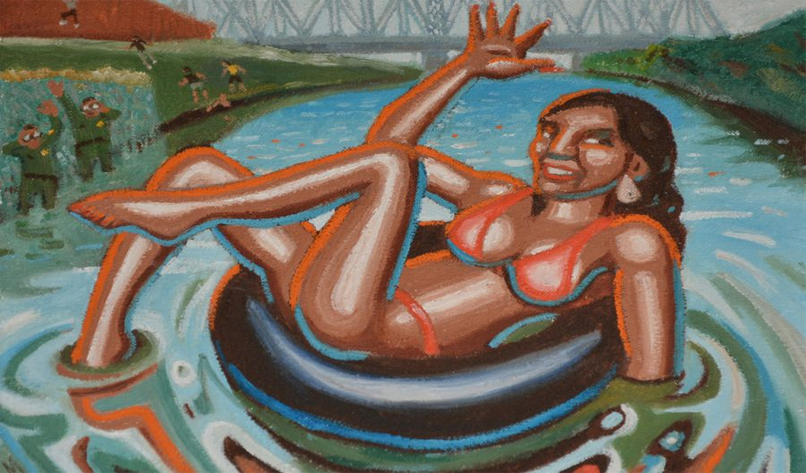

Not surprisingly, some artists have used the idea of the fence or wall itself as a motif. In Brownsville, Texas, the artist-owner of Galeria 409 invited local artists to hang their work on the metal posts of the border fence itself, without US government permission, as a protest to the fencing. The show, if one can call it that, only lasted for 4 hours on March 25, 2010. Art Against the Wall was the literal and protest title endorsed by artists who gathered in Hope Park and hung their work directly on the border fence. The pieces included: piñatas shaped like border patrol agents (complete with sunglasses, walkie-talkies, and binoculars by artist David Freeman); 30 foot ladders made of bamboo and twine; a deflated black inner tube fished out of the Rio Grande river; a colossal funeral wreath; and a painting by artist Mark Clark of a sensual woman in a bikini floating down the Rio Grande in an inner tube, entitled Saludos desde el otro lado (Greetings from the Other Side).

3.3. Imagery in Situ: Za’atari Refugee Camp in Syria

Heretofore, we have seen art that appears in art contexts. These paintings, sculptures and video installations are at home in museums and galleries, works that fit into niche of art as an aesthetic endeavor, an academic discipline. But any consideration of the artistic production of the actual immigrants and refugees, those in camps and those crossing borders in fear for their lives, requires that we examine their art in context. For the most part, these images do not appear in galleries or museums. How could they since they are on the impermanent fabric of refugee camp structures. They cannot be purchased; they cannot be commissioned. This imagery is the product of people who live in less than ideal environments, in the shadows, and often it is in their environment. Rare is it to see or even document this type of production.

This type of in situ refugee art is problematic to discover, since its audience is limited and usually concerned with basic subsistence, first and foremost. While the latter statement is obvious, it is only partly accurate. The Department of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) as structurally integral to many refugee camps, is also the patron of much of the imagery. The UNHCR’s mission is to protect the rights and well-being of refugees all over the world; it is through them that much of the art of these displaced peoples comes. For 65 years, UNHCR has documented both the harsh reality of these camps and the escapist, fantasy art that can be seen within them.

Between 2012 and 2015, a team of Syrian refugees in the Za’atari Refugee Camp worked in partnership with aptART, ACTED, UNICEF, ECHO and Mercy Corps to create a more humane if not whimsical environment in the midst of the deadly Syrian war.

In 2013, the residents created this colorful mural which focused on that which is most treasured in the camp, water. In I Dream Of… , a drab community building became a place of color, light and whimsy, at least briefly. With communities destroyed and lives uprooted, art workshops for decoration sprung up in the Za’atari refugee camp to use community murals to improve what otherwise was hopeless, as in the Water and Rima (Angel) murals.

The Za’atari Camp in northern Jordan has become the world’s second-largest refugee camp with approximately 100,000 residents. While they have escaped the death and destruction of war, these refugees now find themselves in a colorless desert wasteland that contrasts dramatically with their former lush, green native region of Daraa, Syria. With practically no plant or animal life and endless rows of beige tents and caravans, Za’atari is a harsh land of dust storms, heat and blindingly bright sunlight. Lives are on hold and official work is prohibited.

These murals have become some of the few structured activities for youth in Za’atari to engage in. With substandard education and no opportunities for refugee voices to reach out to the world in a positive way, this has become a method for the residents to tell their own stories.

These brightly painted, water infused scenes at first glance seem to have no connection with the reality the camp. But these pictures transcend time and place. They are pictures of painted beauty in a world of suffering and death—flowers, fantastic landscapes and surrealistic portraits.

3.4. The Jungle in Calais, France

With the Syrian War raging on, in spite of multiple failed cease fires, the refugee camp known as The Jungle in Calais, France, has continued to encourage art as therapy and art as social change.

Clearly, art can be used as a powerful advocacy tool to communicate stories for those who have no voice. But that was for the world outside The Jungle. The assumption has always been that art produced in the camps helped to transform the lives of the refugees. Aesthetic and corporeal, art would help change to occur. Yet, when the art is removed and shown to a wider, world audience, it’s not entirely clear that either assumption – change within the camps or an aesthetic revolution – rings true.

3.5. Radical Chic in London

While refugees remain displaced, often forgotten, entrepreneurial art dealers have turned ‘camp’ art into saleable, collectable commodities. During London’s Refugee Week events at Southbank Art Centre from 20-26, 2015, dealers sold to private collectors and museums. Such actions are often seen as ethically problematic if not outright contradictory. 13 In the Fall of 2016, as part of Southbank Centre’s Festival of Love, the show The Calais Jungle (July 9 – October 2, 2016) focused, according to its organizers, “to capture this humanity and provides the context” of the overcrowded refugee camps. 14 The show also sparked protests outside of the Royal Albert Hall.

Whatever else The Calais Jungle show demonstrated, exhibitions like this explore in a contemporary context emerging positions that cast aesthetics as the primary discourse for social, ecological, and political engagement. In other words, the art of the displaced seems, intentionally, to have become a new avant-garde. Is art produced in camps of refugees operating under a conscious, aesthetic system? Is it antithetical to the contemporary aesthetics? Or does it cross multiple disciplines suggesting that political and ontological problems may be best addressed as aspects of aesthetic experience?

4. Conclusion

Exhibitions like those mentioned here are the latest in avant-garde chic. Under the banner of aesthetic activism, elite stakeholders (philosophers, academics, sociologists and critics) discuss such exemplary viewpoints as Accelerationism, Afro-Futurism, Dark Ecology, Extro-Science Fiction, Disobedient Objects, Immaterialism, Object-Oriented Ontology, and Xenofeminism.

Meanwhile the lives of those in contemporary political displacement goes on. Unlike the ill-fated travelers on Gericault’s Raft, the refugees and the displaced often have the time, in their uprootedness, to reflect on their condition in visual form. What is the refugee’s reaction in art? Whatever it might be, at least the imagery and color might make life in these camps a bit more palatable.

Turning our attention to the United States, it is humbling to remember that every generation has had its own ugly reaction to refugees whether they were the Irish, Jews, Vietnamese, Cubans or Haitians. The fears associated with those immigrants, of course, were broadly unfounded.

In fact there was only one time in American history when the fear of refugees wiping everyone out did actually come true: it is celebrated every year in the United States on the last Thursday in November.

5. Acknowledgement

An early variant of this paper was presented at the 9th International Conference on Transatlantic Studies at the University of Central Missouri on October 10-11, 2016. Many thanks to Professor Don Wallace, Department of Criminal Justice, and Professor Kamel Ghozzi, Department of Communication, from UCM for their critiques. This paper was presented at the Character and Home Conference at the University of Dubuque on March 2, 2018. In addition, the author expresses his gratitude for research funding from the Oxford Education Research Symposium, St. Hugh’s College, Oxford University. Thanks also for images provided by the European Migration Network, a subgroup coordinated by the European Commission in Brussels.References

Bermel, N. (2007). Linguistic authority, language ideology and metaphors. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter.

Charteris-Black, J. (2009). Metaphor and political communication. metaphor and discourse. Eds. Andreas Musolff and Jorg Zinken (pp. 97-109). New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Franke, W. (2000). Metaphor and the making of sense: The contemporary metaphor renaissance. Philosophy and Rhetoric, 33(2), 137-153.

Lakoff, G., & Johnson, M. (1980). Metaphors we live by: The University of Chicago Press.

Wee, L. (2006). The cultural basis of metaphor revisited. In Pragmatics & Cognition, 14(1), 111-128.

Footnotes

1.The purpose of this paper is not to direct the reader to distinct national definitions (legal and moral) of various countries’ immigrant issues. Many papers already address this ever-changing issue. For an analytical summary see the ongoing work at The Migration Observatory, part of COMPAS (Centre on Migration, Policy and Society) at the University of Oxford. Retrieved from http://www.migrationobservatory.ox.ac.uk/ . For a very logical discussion of the distinctions between immigrants, refugees and the displaced, read Somini Sengupta’s August 27, 2015 article in the NYTimes. Retrieved from http://www.nytimes.com/2015/08/28/world/migrants-refugees-europe-syria.html?_r=0

History is rife with examples of leaders who manipulate fear to distract, mislead and undermine the will of the very people who put them in power. In this example, I am thinking of the oft quoted portion of FDR’s March 4, 1933 inaugural speech in which he stated “the only thing we have to fear is fear itself”. See Retrieved from https://www.archives.gov/education/lessons/fdr-inaugural/ . Graham, Otis L., Jr. An Encore for Reform: The Old Progressives and the New Deal. New York: Oxford University Press, 1967.

2. History is rife with examples of leaders who manipulate fear to distract, mislead and undermine the will of the very people who put them in power. In this example, I am thinking of the oft quoted portion of FDR’s March 4, 1933 inaugural speech in which he stated “the only thing we have to fear is fear itself”. See Retrieved from https://www.archives.gov/education/lessons/fdr-inaugural/ . Graham, Otis L., Jr. An Encore for Reform: The Old Progressives and the New Deal. New York: Oxford University Press, 1967.

3. The understanding of metaphor in this paper is based on the cognitive and conceptual view of metaphor outlined by Lakoff and Johnson (1980). This theory of conceptualization of metaphor

is a means of understanding something in terms of something else by “mapping” one conceptual domain to another domain. The theory is useful for this methodology since it makes plausible

assumption on a theory level about what expressions may potentially be understood metaphorically. This conceptual view also implies that metaphors are pervasive in everyday visualization. People understand metaphors according to their respective environment, context and culture as Wee (2006) explains that, metaphors are viewed primarily from cognitive perspective as well as their cultural understanding. It should be noted that the field of metaphor studies has grown tremendously in recent years, and now has at least two clear branches. One branch continues the traditional view of metaphor within the context of philosophy of language or of literary studies, in which it primarily viewed as a rhetorical device. The other view is more in line with a cognitive perspective and considers metaphors (in language and in visualization) as a reflection of the world around us. For further reading on linguistic study of metaphor in communication studies, see:

Lakoff, G. & Johnson, M. (1980). Metaphors We Live By. The University of Chicago Press.

Wee, L. (2006). The cultural basis of metaphor revisited. In Pragmatics & Cognition, 14(1): 111-128.

Bermel, N. (2007). Linguistic authority, language ideology and metaphors. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter.

Charteris-Black, J. (2009). Metaphor and political communication. metaphor and discourse. Eds. Andreas Musolff and Jorg Zinken. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. pp: 97-109.

Franke, W. (2000). Metaphor and the making of sense: The contemporary metaphor renaissance. Philosophy and Rhetoric, 33(2): 137-53. Web. 4 Dec. 2009.

4.Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/world/2015/sep/02/shocking-image-of-drowned-syrian-boy-shows-tragic-plight-of-refugees.

5. The bigoted cry of ‘love it or leave it’ did not start, of course, with the current US presidential race.

6. We know this detail because of the testimony of the 15 survivors to the press.

7. There was no search effort mounted to rescue the Medusa since the fate of the ship had not immediately been known. According to contemporary newspaper accounts, the meeting was purely serendipitous.

9. Strangely enough nobody commissioned the work but the artist believed that the incident he was portraying would generate great interest from the public and in so doing he believed his career would take off.

10. The crewman is said to be Jean Charles. His placement as the sole actor set to insure the rescue of the raft is probably the result of Géricault’s abolitionist sympathies.

11. The painting was not purchased when it was displayed in the Salon of 1819. Géricault took it on tour to London where admission to see it made him financially secure. Finally, upon the artist’s death, it was priced at 6,000 francs at the posthumous sale of the artist's possessions. Even then it did not pass directly to the state collection. It was bought by Dedreux-Dorcy, a friend of Géricault, for an additional five francs. Later he sold it to the State for the same amount.

12. See Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8u9a3Om7dZ4 to view the performance, which dates from 2013. Interestingly, this performance piece is not listed among her oeuvre at her site: Retrieved from http://www.patriciaruizbayon.com/menu.htm.