Crafting Values in Organizational Change Processes

Sjaña S. Holloway1

A. Georges L. Romme2

Evangelia Demerouti3

1Owner & Founder at E.T. P. Enterprise, The Netherlands. |

AbstractThis paper explores employees’ use of organizational values in the context of a post-merger integration (PMI) change process, which entails adopting a new set of values. Within such a dynamic corporate context, organizational values may assist employees in proactively managing their work performance and job satisfaction by putting organizational values into practice and using them (‘crafting’) in the context of work. A four-week diary study was conducted in which 71 employees participated. Diary records and validated questionnaire data were collected during a post-merger integration process in a multi-national corporation, and were then analyzed using multi-level modelling. This study suggests that using and practicing organizational values can affect people's motivation to act proactively in changing work settings. We discuss the implications of our findings for future work in helping organizational members craft their work by drawing on organizational values for sustainable collaboration. |

Licensed: |

|

Keywords: |

|

| (* Corresponding Author) |

1. Introduction

Organizational values form the cornerstone of a company’s identity since they reflect the company’s principles and mission. Importantly, these values have to be adopted and put into active use by the employees. This study examines employees’ use of organizational values in the context of a post-merger integration (PMI) change process. Within such a dynamic corporate context, employees may want to use organizational values to proactively manage their work performance and job satisfaction. This study also explored whether using and practicing organizational values can affect people's work engagement.

To address this research challenge, work engagement, which is a positive, fulfilling and work-related state of mind that is characterized by vigor, dedication and absorption, (Schaufeli & Bakker, 2010; Schaufeli, Salanova, González-Romá, & Bakker, 2002) was selected. Work engagement has been shown to be important for both organizations and employees. Previous research on work engagement has examined its positive relation to personal and job resources (Bakker & Demerouti, 2007; Kira, van Eijnatten, & Balkin, 2010). Studies have suggest that organizational values have both stable and shifting capacities (Beauregard, 2011; Seevers, 2000; Zueva-Owens, Fotaki, & Ghauri, 2012) for example, in guiding the behavior of employees (Adler & Gundersen, 2007; Rhoades & Eisenberger, 2002) enabling or inhibiting organizational change (Amis, Slack, & Hinings, 2002) and influencing the development of organizational strategy (Bansal, 2003; Carlisle & Baden-Fuller, 2004).

Drawing on a study conducted in a large corporation that had undergone through a merger, we explore the within-person variability in value use by collecting longitudinal data (over a period of four weeks) and subsequently analyzing these data. This approach serves to examine organizational value use as an extension to the well-established nomologic between work engagement and resources (i.e. personal and job) (Bakker & Demerouti, 2008; Xanthopoulou, Bakker, Demerouti, & Schaufeli, 2007, 2009). We also introduce the concept of the use of organizational values as a proactive mediator in the relation between work engagement, work performance, and satisfaction.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. The next section outlines our conceptual framework. We then describe the methods and general measurements adopted. Finally, we outline and discuss the main results of this study.

2. Conceptual Framework

To understand the relationship between organizational value use and work engagement (i.e., work performance and job satisfaction), we adopt a holonic interpretation of social and human development (Edwards, 2005; Wilber, 1999, 2000). This holonic lens serves to differentiate the intentional, behavioral, social, and cultural domains (Edwards, 2005).

In the domain of intentional thought, values are used in the interest of one’s own personal interpretation of a value. In the behavioral domain, values are used in the context of setting goals with organizational values in accordance with one’s own purposes. Using values in the (social) roles domain means propagating these values to and with other people. Value use in the cultural domain means adopting or adapting a particular value in the work done with others.

The holonic perspective is instrumental in exploring the relationship between the subjective (cf. intangible experiences) and the objective (cf. tangible behaviors) as an aspect of reality, and as such the balance between interior-personal and cultural life as well as between exterior-behavioral and functional life (Cacioppe & Edwards, 2005; Edwards, 2005).

2.1. Use of Values

Organizational values can have a functional or formal linguistic function in communication (Chomsky, 1986; Chomskye, 2005; Givón, 1993; Jayaseelan, 1993). The formal use is characterized by the innate structure of the values themselves. The formal definitions produced by the organization and its efforts to create a particular atmosphere would fall under this category. The functional use would be the holonic qualities that values have in language orientation, including intention/thought/cognition (Dummett, 1993) functionalist behaviors (Pandey, 2004) social roles (Bauman & Briggs, 1990; Itkonen, 1978) and cultural characteristics (Carey, 1989, 2008) in which these organizational values are used. The proactive use of organizational values by an individual or agent is part of a developmental iteration process which occurs in the communication with others. This iterative process is part of innovative knowledge discovery and developmental endeavors (Kerssens-van Drongelen, 2001).

In this study, the development of value use or value crafting (i.e., interpreting, applying, propagating, and adopting) relates to a person or agent using a particular organizational value in relation to their context, situation, and engagement (i.e., work performance and job satisfaction).

As such, the idea of balancing the personal (thoughts) with cultural life and the behavioral (actions) functional life (Cacioppep & Edwards, 2005b; Cacioppes & Edwards, 2005a) serves to better understand the relation between work engagement and use of values in the context of developing positive perceptions of one’s own work performance and satisfaction.

We suggest the use of organizational values within an organization consists of developing intentional thought about any given value, exhibiting behavior by setting goals with organizational values, propagating these values in (social) roles to and with other people, and adopting or adapting a particular value culturein applying this in the work done with others (Holloway, van Eijnatten, & van Loon, 2011). Therefore, organizational values can embody the overarching formal intent of an organization and can also be flexible enough for the functional intent of employees to use in their work.

2.2. The Role of Resources

The inclusion of resources is important in terms of their nomological relation with work engagement. We focused on two job resources and two personal resources that may be important for value use: participation and leadership respectively, and organization-based self-esteem (OBSE) and general self-efficacy (GSE).

Employee participation is fueled by the degree to which workers believe they can make decisions, participate, and have an impact at work (Weber & Weber, 2001; White & Ruh, 1973).

One approach to participation proposes that management uses employee participation to enhance employee attachment as part of a strategy to subjugate them (Doughty & Rinehart, 2004; Joensson, 2008) while a more humanistic view would see participation as a benefit to growth, inclusion, and identification with the organization (Fuller et al., 2006; Joensson, 2008).

Therefore, in our study participation is considered to be an exterior expression of individual behavior in the workplace.

Leadership is the ability to affect people within an organization toward the achievement of goals (Robbins & Coulter, 2002). Leaders within an organization help create, develop and foster its culture by reinforcing norms and behaviors expressed within the boundaries of the organization.

The link between both tactical and strategic thinking lies with a leader’s ability to build the culture and value needed to move forward. Leaders can show the direction of the company goals through their communications (Bass & Avolio, 1993; Ogbonna & Harris, 2000). In this way, leaders can create mechanisms for cultural development and the reinforcement of norms and behaviors as expressed within the boundaries of the organization’s culture. In the present study, leadership is therefore considered to be an exterior expression of social role behaviors within the organizational community.

The construct of OBSE developed by Pierce, Gardner, Cummings, and Dunham (1989) reflects the self-perceived value of individuals and their membership within an organization and its various contexts. The ability of individuals to meet demands in many organizational contexts and their tendency to feel successful can spill over into particular situations (Chen, Gully, & Eden, 2001; Yeo & Neal, 2006).

In this study, OBSE refers to an individual’s inner thoughts and feelings regarding the organizational community.

GSE is perceived as reflecting a more general degree of domain-specific functioning (Schwarzer & Jerusalem, 1995). GSE emerges over the course of a person’s life and can expand as successes are accumulated and associated with other self-evaluating constructs (Chen et al., 2001; Judge, Bono, & Locke, 2000).

In this study, GSE represents individuals’ inner thoughts and feelings about themselves. Resources are structural or psychological assets that may be used to facilitate performance, reduce demands, or generate additional resources (Bakker & Demerouti, 2007; Demerouti, Bakker, Nachreiner, & Schaufeli, 2001; Kira et al., 2010).

2.3. Work Engagement and the Research Hypotheses

Work engagement is characterized by vigor, dedication and absorption (Schaufeli & Bakker, 2010; Schaufeli et al., 2002) as “absorption is a distinct aspect of work engagement that is not considered to be the opposite of professional inefficacy” (Schaufeli & Bakker, 2003). Items related to absorption were not used in this study.

In the current study, the characteristics of vigor and dedication were examined on a weekly-level, therefore we use the t

erm weekly work engagement (cf. (Bakker & Bal, 2010; Bakker & Sanz-Vergel, 2013)). Vigor is associated with high energy levels and mental resilience while working with the willingness to invest effort in the work being done, regardless of the circumstance. Dedication is associated with experiencing a sense of significance, enthusiasm, inspiration, and challenge while working. To put it differently, vigor and dedication are considered to be associated with energy, activation and identification (Schaufeli & Bakker, 2003). In this respect, job resources enhance daily functionality as well as reduce work demands at the associated psychological and physiological price of a person.

Job resources refer to the organizational aspects of a job that are supposed to have the potential for inherent and extrinsic motivational properties to help employees meet their working goals (Demerouti et al., 2001; Xanthopoulou et al., 2007).

Personal resources can be a source of strength and allow an individual to develop and build upon external work skills, which can manifest themselves in autonomous and social actions (Kira et al., 2010). Research has shown the important relationship between resources and employee engagement, such that work engagement has a positive impact on work performance (Bakkerp, 2009). Based on the above reasoning, the following hypothesis is derived:

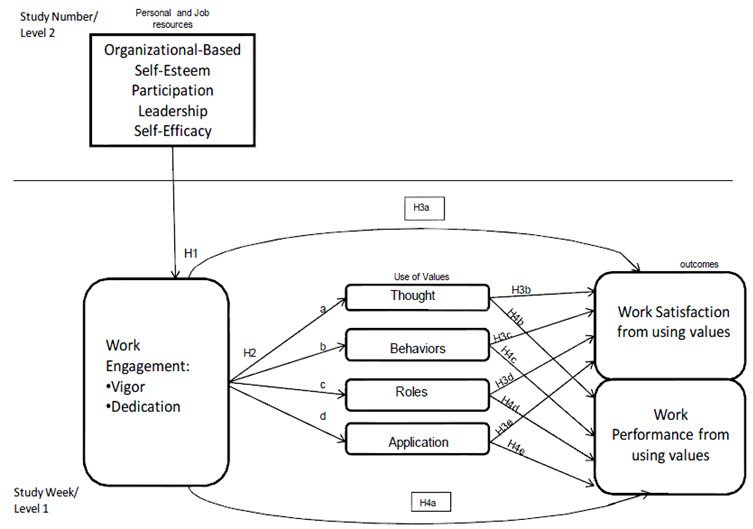

H1: General perceptions of work and personal resources (i.e. OBSE, Participation, Leadership, and Self-efficacy) are positively associated with weekly work engagement.

There is also an interest in the connection between weekly work engagement and the four developmental domains.

Therefore, we look at how weekly work engagement is connected to proactively using organizational values in accordance with the holonic view taken in the research. Previous research has found work engagement to be positively related with in-role and extra-role performance (Halbesleben & Wheeler, 2008; Schaufeli, Bakker, & Salanova, 2006) and unit performance (Harter, Schmidt, & Hayes, 2002). Prior research has also revealed that work environments where employee resources and engagement were high resulted in better team results (e.g. Salanova and Peiró (2005)).

Work engagement has also mediated the relationship of self-efficacy, task and contextual performance (Xanthopoulou, Baker, Heuven, Demerouti, & Schaufeli, 2008). To provide clarification of the relation between weekly work engagement and the use of organizational values, because engaged employees may be more willing to invest effort in adopting new values, we examine the development of intentions (thoughts), set goals (behaviors), convince others (roles), and (applications) of organizational values in work (SjañaSHolloway et al., 2011). We thus hypothesize:

H2 a-d: Weekly work engagement is positively associated with the use of values as expressed in (a) thoughts (b) behaviors (c) roles and (d) applications.In this study, individual and collective decision-making processes explore the relationship between the subjective (cf. intangible experiences) and the objective (cf. tangible behaviors) (Edwards, 2005). Taking the vantage point that this is ever-present, we can argue that there is a relation between work engagement and perceived satisfaction with using organizational values. We thus hypothesize:

H3a: Weekly work engagement is positively associated with satisfaction about the result of using organizational values.

H3b-e: The use of organizational values expressed in (b) thoughts, (c) behaviors, (d) roles and (e) applications (partially) mediates the relationship between weekly work engagement and satisfaction with the result of using organizational values.

We can also argue that there is a relation between work engagement and perceived work performance with using organizational values (Hollowaye, 2014). We thus hypothesize:

H4a: Weekly work engagement is positively associated with perceived work performance with using organizational values.

H4b-e: The use of organizational values expressed in (b) thoughts, (c) behaviors, (d) roles, and (e) applications (partially) mediates the relationship between work engagement and perceived work performance with using organizational values.

Figure-1. Model of hypothesized relationships between work and personal resources, work engagement, use of organizational values, work performance, and satisfaction with the result of the use of a value.

3. Methods

The present study was conducted in ten subsidiaries of a newly merged international corporation located in the Netherlands, the United Kingdom, Denmark, Iceland and the USA. The corporation planned to have a new cultural structure based on the development of new organizational values. An open campaign was set up within the subsidiaries to assist in the development of new corporate values. Eight new organizational values (e.g. commitment, innovation, fun, success, teamwork) were developed that were focused on social concerns (i.e. relating to customers, vendors, and interdepartmental teamwork) within the organization along with a new vision and mission for the corporation. Series of meetings were held to address the direction of the newly merged corporation and development of a strategy to promote the new cultural and structural changes throughout the organization. Participants for our study were drawn from the more than 550 people with various functions in the company (e.g. managers, engineers, and technicians) who participated in those meetings.

An email was sent out to the HRM managers of each of the subsidiaries and to the corporate HR director to obtain consent to contact participants of those meetings. Participants had to meet two main requirements for participation: (1) they needed to have access to the Internet or, alternatively, state their need for paper-and-pencil surveys; and (2) they needed to have adequate English language skills. After receiving permission from all HRM managers, we were able to access the email addresses and locations of all participants. An email was sent describing the research to introduce the study and address any questions participants might have regarding the study.

At the end of that week, we sent an invitation to participate in the research to all participants. One hundred participants who had attended the company meetings volunteered to participate in the study. To encourage participation, we offered organizational feedback as well as contact with one of the researchers at the end of the research period for personal analysis. This resulted in an initial group of one hundred participants, from which 71 volunteers from nine different subsidiaries completed all four weeks of the study.

The study required people to complete a general questionnaire at the start of the study and subsequent diaries for four consecutive weeks. Participants filled in the first weekly survey at the end of the same week in which they filled in the general questionnaire.

The weekly surveys had to be completed and delivered (usually on Friday, but at least before Monday morning) for four consecutive weeks. After completion of the first weekly survey, 15 people would only be able to continue in a less consistent manner (e.g. due to vacation). Thus, the weekly diary period was extended to last eight consecutive weeks.

This allowed those people who were unable to participate in consecutive weeks to still participate in the full four-week study. A link to an on-line diary was sent to volunteers on the Thursday morning of each week. On Monday of the following week, a reminder email was sent out to those participants who had not filled in the diary from the previous week.

When participants missed a week in the survey, they could start again the following Thursday. The people who used a paper diary were sent a general survey and four weekly survey booklets. They were asked to mail the general survey and booklets back at the end of the four weeks.

An on-line diary study was used for data collection. The term diary study refers to a classification of methods using daily or weekly experience-sampling, event-sampling, or other studies to assess episodic changes (Ohly & Fritz, 2010; Sonnentag, 2003). Diary studies allow researchers to better understand the context of work. It allows for the capture of weekly events, and the analysis of episodic fluctuations over an extended period (McCullough, Bono, & Root, 2007; Ohlys, Sonnentag, Niessen, & Zapf, 2010). These methods have been used to capture the weekly cycles of change rather than linear changes in organizations (Binnewies, Sonnentag, & Mojza, 2009; Larsen & Kasimatis, 1990).

Another benefit of diary studies is the avoidance of strong retrospective bias (e.g. recall) that may occur when data are collected weeks or years after events actually happened (Affleck, Zautra, Tennen, & Armeli, 1999; Bolger, Davis, & Rafaeli, 2003; Tennen, Suls, & Affleck, 1991). We used the internet to capture information from participants, who were spread around the globe (Carter & Mankoff, 2005; Fricker & Schonlau, 2002). The online version of the diary was completed by 69 participants, while 2 participants chose to complete a paper-based version.

In total 71 individuals from different subsidiaries in the USA (N=15), Denmark (N=11), The Netherlands (N=22), Iceland (N=20), and the UK (N=3) completed all four weeks of the study, giving a response rate of 70%. The typical employee was male (98%) female (2%); 45 years of age (SD =14); had 19 years organizational tenure (SD=13); worked 38 hrs/week (SD=17); had a high school education (16%), bachelors (34%), masters (30%) or other vocational training (20%).The sample size was adequate to test the hypotheses with 4 x 71 = 284 data points (cf. Hox (2002)).

4. General Measures

4.1. Personal resources

General Self-Efficacy (α = .81) was assessed with three items (e.g. ‘I am confident that I could deal efficiently with unexpected events’) based on a scale developed by Schwarzer and Jerusalem (1995). These items were scored on a 7-point scale (1= ‘Strongly agree’ to 7= ‘Strongly disagree’).

Organizational-based self-esteem (α = .92) was assessed with three items (e.g. ‘The organization believes in me’), based on scales developed by Pierce et al. (1989). These items were scored on a 7-point scale (1= ‘Strongly agree’ to 7= ‘Strongly disagree’).

4.2. Job Resources

Leadership (LMX) (α = .89) was assessed with three items (e.g. ‘My immediate supervisor understands my problems and concerns related to my work’) adapted from Scandura, Graen, and Novak (1986). These items were scored on a 7-point scale (1= ‘Strongly agree’ to 7= ‘Strongly disagree’).

Participation (α = .81) was measured with 3 items (e.g. ‘I can contribute to the shaping of changes’), based on scales developed by Miller, Johnson, and Grau (1994). These items were scored on a 7-point scale (1= ‘Strongly agree’ to 7= ‘Strongly disagree’). NB: for both job and personal resources, higher scores indicate a lower level of the respective resource.

4.3. Weekly measures

Work engagement (α = .92) was measured with vigor and dedication items (i.e. vigor: 3 items: ‘During this past week at work, I felt bursting with energy’; Dedication, 3 items:

‘This past week I’ve been enthusiastic about my job’) from the Utrecht Work Engagement scale (Schaufeli et al., 2006). These items were adjusted to reflect the past week and scored on a 5-point scale (1 = ‘not at all’ to 5 = ‘very much’).

Use of values was measured with a single item by asking participants if they had thought about-, convinced others to use-, set a goal with-, or applied a particular value over the course of the workweek. There were eight organizational values (e.g. commitment, innovation, and teamwork) and we used the average of the values over the course of the four-week study.

The single-item measures, (i.e. ‘what did you do with the value of XYZ, this week?’; ‘I set a goal with this value, this week’; ‘I convinced others to apply the value to their work’; ‘I thought about this value, this week’; ‘I actually applied this value to my work, this week’), were scored with a report mark 0 = no, 1 = yes. If yes, we requested a specific example be given to indicate what particular goal, what role in convincing others to use the value, and what thought or action had been taken.

This was used to gather information about whether the respondent used specific organizational values over the course of the study. If a person did not use a particular value, there was the option to go to the next value and answer an identical set of questions referring to the four perceived uses of organizational values. There was also an ‘other’ option for participants to give responses that were (perceived to be) outside the four theoretical summations of value use.

Perceived satisfaction with the use of value was measured with a single item (i.e. ‘Are you satisfied with the outcome of using the value of XYZ, this week?’). This was scored on a 5-point response scale (1= ‘very dissatisfied’ to 5= ‘very satisfied’).

Perceived creation of better work performance with the use of organizational values was measured with a single item, (i.e. ‘Did the use of XYZ help you create better work performance, this week?’). This was scored on a 5-point response scale, (1= ‘not at all’ to 5 = ‘very much’).

The last two constructs were measured with a single item in a Likert-scale format. Previous research by Wanous, Reichers, and Hudy (1997); Wrzesniewski and Dutton (2001) and Nagy (2002) suggest these single items are reliable and valid when one is interested in a global evaluation of a construct.

4.4. Statistical Analysis

The week-level data are nested within individuals. For this reason, a multilevel analysis approach was adopted. Multilevel analysis refers to statistical methods that are used for data sets with different levels of analysis involving nested structures.

Grand mean centering was conducted for level-two variables and person centering for level-one variables. Grand mean centering and person centering were done as recommended by Ohlys et al. (2010).

5. Results

5.1. Descriptive Statistics and Direct Effects

Table 1 shows the means, standard deviations, and correlations among all the study variables. Week-level variables across the 4 weeks were averaged to correlate them with variables measured at the general level. This was done only for the calculation of the correlations, whereas all other analyses were conducted with the original, multi-level data.

| Mean | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | |

| General Variables | |||||||||

| 1. Self-efficacy | 1.697 | .554 | - | ||||||

| 2. Participation | 2.047 | .698 | .244** | - | |||||

| 3. OBSE | 2.024 | .727 | .129* | .474** | - | ||||

| 4.Leadership | 2.268 | .792 | -.024 | .355** | .308** | - | |||

| Week-level variables | |||||||||

| 5. Job satisfaction | 3.673 | .807 | -.071 | -.142* | .146* | -.051 | - | ||

| 6. Work performance | 3.154 | .843 | -.048 | -.257** | -.260** | -.118* | .739** | - | |

| 7. Work engagement | 3.44 | .869 | -.027 | -.300** | -.498** | -.220** | .507** | .643** | - |

| 8. Use of value | .264 | .169 | -.252** | -.148* | -.205** | -.081 | .208** | .316** | .274** |

Note: ** Correlation is significant at the 0.01 level (2-tailed) *Correlation is significant at the 0.05 level (2-tailed). |

5.2. Preliminary Analysis

The variability of the week-level measures was examined. Results showed that 64% of the variance in work engagement, 37% of the variance in satisfaction, and 52% in work performance were attributed to between-person variations.

For the use of organizational values thinking and setting goals, this was 83% and 82%, and for application and convincing of others, it was 54% and 56%, respectively. The findings suggest that a substantial proportion of the variance can be explained by within-person fluctuations across the 4 weeks, which supports the use of multilevel analysis.

5.3. Testing the Hypotheses

According to hypothesis 1, general perceptions of work and personal resources (i.e. (a) OBSE, (b) Participation, (c) Leadership and (d) Self-efficacy) relate positively to weekly work engagement. We tested this hypothesis for work and personal resources, while controlling for years at the company as a level-two variable.

Results of the multilevel analysis show that the relation between OBSE and work engagement (γ = -.538, SE = .114, t = -4.895, p < .001) was significant and negative rather than positive as we predicted. The other resources Participation (γ = .086, SE = .123, t = .699, n.s.) Leadership (γ = .045, SE = .098, t = .459, n.s.) and Self-efficacy (γ = .075, SE = .133, t = .563, n.s.) were not significant. Therefore, hypothesis 1 was rejected.

According to hypothesis 2, employee work engagement at the week level is positively related to using organizational values: (a) thoughts; (b) behaviors; (c) roles; and (d) applications. We tested this hypothesis for work engagement and each proposed ‘value use’(i.e thoughts, behaviors, etc.) separately, while controlling for years at the company as a level-two variable. Results of the multilevel analysis showed thoughts (γ =.056, SE = .023, t = 2.434, p < .001), behaviors (γ =.046, SE = .018, t = 2.555, p < .001), roles (γ =.056, SE = .019, t = 2.947, p < .001), and applications (γ =.144, SE = .021, t = 6.857, p < .001) to be significantly and positively related to work engagement. All four domain interpretations of value use are significant and predicted by weekly work engagement. Therefore, hypotheses 2a, 2b, 2c and 2d are confirmed.

Hypotheses 3 and 4 suggest a mediation effect; hence several models were nested. Model 1 is the null model where the intercept is the only predictor. Model 2 includes work engagement and the number of years at the company serves as a control variable. In model 3, we included the use of organizational values as predictors.

To test the hypotheses, three conditions of mediation must be met (Mathieu & Taylor, 2007): (1) work engagement at the week level should be positively related to using organizational values; (2) use of organizational values should be positively related to perceived work performance or satisfaction with the result of using a value; (3) after including the mediator, the previously significant relationships between work engagement and work performance and satisfaction, respectively, should either turn insignificant (full mediation) or significantly weaker (partial mediation) (Baron & Kenny, 1986; Pitariu & Ployhart, 2010).

To test the significance of the indirect effects, we used the parametric bootstrap method recommended by Preacher, Zyphur, and Zhang (2010) to create confidence intervals. We used the online interactive tool developed by Selig and Preacher (2008) which generates an R-code to obtain confidence intervals for the indirect effect.

Hypotheses 3a-e suggest that (a) work engagement is positively associated with the perceived satisfaction regarding the result of using a value; and the relationship between employee work engagement and perceived satisfaction with the result of using a value is (partially) mediated by the use of organizational values by (b) thoughts, (c) behaviors, (d) roles, and (e) applications. We can conclude from the earlier analysis of hypothesis 2 that condition 1 of mediation has been met.

There is a relation between work engagement and the use of organizational values. Condition 2 of mediation, the use of organizational values should be positively related to satisfaction with the result of using a value, is met for the application of organizational values, which is positively and significantly related to satisfaction with the result of the use of a value.

As for condition 3 of mediation, inclusion of the application of organizational values in work, the relationship between weekly work engagement and satisfaction becomes substantially weaker. The results can be seen in Table 2 (see model 2). Therefore, partial mediation is established and hypotheses 3a and 3e are confirmed, but hypotheses 3b, 3c, and 3d are rejected. This was because thoughts, behaviors and roles (mediators) were not related to satisfaction (outcome), and as such condition 2 was not met. The Monte Carlo test showed that the indirect effect of work engagement to satisfaction with the result of using a value through application was significant and positive (lower bound = .069 to upper bound = .263) since the biased corrected 95% confidence interval did not include zero.

| Perceived satisfaction from using values | Null |

1 |

2 |

||||||

| Variables | Estimate |

SE |

t |

Estimate |

SE |

t |

Estimate |

SE |

t |

| Intercept | 3.673 |

.07 |

52.471*** |

3.673 |

.07 |

52.5*** |

3.673 |

.07 |

52.5*** |

| Years at company | .002 |

.004 |

.5 |

.002 |

.004 |

.5 | |||

| work engagement | .480 |

.078 |

6.154*** |

.322 |

.083 |

3.879*** | |||

| thought | -.100 |

.235 |

-.425 | ||||||

| set goals | -.156 |

.295 |

-.528 | ||||||

| role | .336 |

.292 |

1.150 | ||||||

| applied | 1.076 |

.244 |

4.409*** | ||||||

| - 2 x log | 636.653 |

601.791 |

580.864 | ||||||

| Δ – 2 x log | 34.86*** |

20.927*** | |||||||

| Δ df | 2 |

4 | |||||||

| Level 1 (Within-Person) Variance | .40 |

.03 |

.35 |

.03 |

.31 |

.03 |

|||

| Level 2 (Between-Person) Variance | .24 |

.05 |

.26 |

.06 |

.26 |

.05 |

Note: ***Correlation is significant at the 0.001 level. |

Hypotheses 4a-e suggest that (a) work engagement is positively related to perceived work performance with the result of using organizational values; and the relationship between employee work engagement and perceived work performance with the result of using organizational values is (partially) mediated by the use of organizational values expressed in (b) thoughts, (c) behaviors, (d) roles and (e) applications. The confirmation of hypothesis 2 implies that condition 1 of mediation has been met: there is a significantly positive relation between work engagement and the use of organizational values.

Condition 2 of mediation implies that using organizational values should be positively related to work performance; this condition was met for the application of organizational values and the convincing of others to use organizational values (i.e. roles). These two value use conditions that are positively and significantly related to work performance see Table 3, model 2).

As for condition 3 of mediation, inclusion of the application of organizational values in work, the relation between weekly work engagement and performance becomes substantially weaker; therefore, this condition was also satisfied.

These results are presented in Table 3, model 2. Therefore, we conclude there is partial mediation in the form of the confirmed hypotheses 4a, 4d and 4e while hypotheses 4b and 4c are rejected. As thoughts and behaviors (mediators) were not related to performance (outcome), condition 2 was not met.

The Monte Carlo test showed that the indirect effects of work engagement to performance through roles and applications were significant and positive (lower bound = .013 to upper bound = .018 and lower bound = .066 to upper bound = .240, respectively).

| Perceived work performance from using values | Null |

1 |

2 |

||||||

| Variables | Estimate |

SE |

t |

Estimate |

SE |

t |

Estimate |

SE |

t |

| Intercept | 3.154 |

08 |

39.425*** |

3.154 |

.08 |

39.425*** |

3.154 |

.08 |

39.425*** |

| Years at company | .-003 |

.005 |

.-6 |

.-003 |

.005 |

.-6 |

|||

| work engagement | .516 |

.069 |

7.478*** |

.349 |

.072 |

4.847*** |

|||

| thought | -.181 |

.205 |

-.883 |

||||||

| set goals | .048 |

.257 |

.187 |

||||||

| role | .598 |

.254 |

2.354* |

||||||

| applied | .998 |

.212 |

4.708*** |

||||||

| - 2 x log | 619.252 |

569.838 |

540.768 |

||||||

| Δ – 2 x log | 49.414*** |

29.07*** |

|||||||

| Δ df | 2 |

4 |

|||||||

| Level 1 (Within-Person) Variance | .34 |

.03 |

.27 |

.02 |

.24 |

.02 |

|||

| Level 2 (Between-Person) Variance | .37 |

.08 |

.38 |

.08 |

.39 |

.07 |

Note: ***Correlation is significant at the 0.001 level. |

6. Discussion

The objective of this study was to examine employees’ use of organizational values in the context of a post-merger integration (PMI) change process. By adopting a holonic interpretation of social and human development (Edwards, 2005; Wilber, 1999, 2000) this study identified and empirically examined the relationship between organizational value use, work engagement and personal and job resources in a dynamic corporate context, where employees may want to use organizational values to proactively manage their work performance and job satisfaction.

Our analysis demonstrates that the work engagement of employees is positively related to their work performance and job satisfaction about using values. Specifically, the use of organizational values in weekly work (partially) mediates the relation between work engagement and perceived employee work performance. Also, organizational values in weekly work (partially) mediate the relation between work engagement and perceived satisfaction with value use. Our findings suggest that employees used organizational values to apply organizational values and convince others to use organizational values in work.

Although hypothesized, we failed to find a direct relation with all of the selected resources (i.e. job and personal) and weekly work engagement. OBSE was the only resource found to be significantly and negatively related to weekly work engagement. This finding may be considered an anomaly because the influence of personal resources to motivate employees has been identified in previous work (Hackman & Oldham, 1980; Piccolo & Colquitt, 2006). Moreover, the relationship between work engagement and job resources has been documented in prior research as well (Demerouti et al., 2001; Xanthopoulou et al., 2008).

The nomological relation between personal and job resources and work engagement is well established. However, in the context of the current study, involving major organizational changes as a result of post-merger integration efforts, the inclusion of intersubjective and symbolic representation of the organization (i.e. values) may have undermined the subjective awareness and individual meaning of resources (i.e. job and personal) at the time of this study. In such an instance, the subjective meaning of resources may be void of fixed meaning and more fluid in their interpretation and representation.

As hypothesized, we did find that weekly work engagement is positively related to the holonic interpretation of social and human development (Edwards, 2005; Wilber, 1999, 2000) used in this study. This holonic lens served to differentiate the development of intentional thoughts, behaviors, (social) roles, and the application of values.

Our findings indicate that work engagement for the participants in this study is, to a large extent, directly associated with the level of satisfaction regarding the result of the use of a value, and with perceived work performance. The relationship between work engagement and perceived satisfaction and performance is consistent with earlier studies on work engagement (Beauregard, 2011; Schaufeli & Bakker, 2010; Zueva-Owens et al., 2012).

In addition, we hypothesized the use of values mediated the relationship between weekly work engagement and the outcome of both perceived satisfaction and work performance. In both cases, ‘thoughts’ and ‘behaviors’ were not significant. However, (social) roles and application were significant in both cases. The majority of previous research on employee proactivity in the workplace targeted aspects of work tasks, comprehension of work, and social roles within work (Berg, Dutton, & Wrzesniewski, 2013; Wrzesniewski & Dutton, 2001).

However, prior work has not explored whether using and practicing organizational values can affect people's work engagement. In the current study, organizational values were being deliberately used or put into practice as flexible mechanisms for facilitating or provoking proactive behavior in the workplace.

6.1. Implications for Practice

The impact of organizational values on employees has been identified as an important factor in employees’ work performance, morale, health, and ability to cope with structural and cultural changes within an organization (Beauregard, 2011; Hobfoll, 2002; Zueva-Owens et al., 2012). Our results suggest that employees used organizational values within a dynamic corporate context (i.e. M &A and PMI), which motivated them to act proactively.

As such, the empirical results are important for organizational change processes, particularly with regard to how values can be deliberately used in the workplace (Holloway et al., 2011; Hollowaye, 2014). Bandura (1969) emphasized that people are more likely to perform and enact new behaviors if the new behaviors are pertinent and beneficial to their lives. Thus, our findings imply that organizational values could be beneficial for creating new behaviors for all stakeholders in an organizational change process.

Our analysis demonstrates the use of organizational values in weekly work (partially) mediates the relation between work engagement and the study outcomes. In our study, individuals applied values in their work, and by convincing others to use values, during a corporate change process. This implies that teamwork may be substantially enhanced by actively using organizational values.

6.2. Limitations and Future Research

A key limitation of this study is that the dataset was comprised of people who were selected to participate in a transition meeting within a company at the PMI stage. Moreover, the participants who volunteered to take part in the study were more likely to be positive and open to the idea of using organizational values than people who decided not to participate. The group also primarily involved managers. We therefore need to be cautious in generalizing these findings beyond this rather homogeneous group.

Another limitation is that we focused on perceived satisfaction and work performance and value usage at the individual level, rather than the group or departmental level. Future research could include work groups and more types of values (e.g. national and personal). Further research is also needed to examine the contextual conditions of our findings with regard to subjective awareness and individual meaning of organizational values in different settings and organizations.

It may also be worthwhile to investigate the changing nature of organizational values as a construct. As an example, organizational citizenship behaviors (Bateman & Organ, 1983) were historically focused on five main categories (i.e. altruism, conscientiousness, sportsmanship, courtesy, and civic virtue). Dekas, Bauer, Welle, Kurkoski, and Sullivan (2013) pointed out that modern working environments have fundamentally changed and require a broader examination of constructs. This is also the case for organizational values, since their influence may go far beyond the espousal of leaders (Brown & Treviño, 2009; Cha & Edmondson, 2006; Fanelli & Misangyi, 2006).

In modern work environments, employees, stakeholders, social media, and other actors (Kraatz, Ventresca, & Deng, 2010; Suddaby, Elsbach, Greenwood, Meyer, & Zilber, 2010) are also influencers of organizational values. Putting organizational values into practice (Cha & Edmondson, 2006; Holloway, van Eijnatten, Romme, & Demerouti, 2016; Sjaña S Holloway et al., 2011; Schatzki, 2002) is the next step in the research stream of organizational values in order to draw on their potential as connectors for the various streams of influence that are part of organizational change processes. This can be identified classically as structures, process, and context (Hannan & Freeman, 1984; Pettigrew, Woodman, & Cameron, 2001; Van de Ven & Huber, 1990). It is worthwhile for future researchers to investigate more deeply in how organizational values can be used/crafted and put into practice in order to promote sustainability and innovation (Garud & Gehman, 2012; Garud, Gehman, & Kumaraswamy, 2011) and actionable knowledge development (Gherardi, 2006; Sjana S Holloway et al., 2016; Nicolini, 2011).

Accordingly, future research can serve to develop a broader and deeper understanding of the use of organizational values in different organizational contexts. In doing so, one can examine enduring effects as well as less enduring effects beyond the limitation of the data collection period in our study.

In this study, perceptions of behavior were measured. The survey is a self-report measure, which may be biased in terms of compliance effects.

We assumed the amount of time a person uses organizational values would be restricted at this stage, and in order to be less burdensome on participants, a weekly questionnaire was decided upon as the most informative and least taxing (cf. (Bakker & Bal, 2010; Totterdell, Wood, & Wall, 2006)). Future research will need to test whether other types of data (e.g. qualitative and quantitative methods) produce similar or highly different results.

6.3. Conclusion

In this paper, we have studied how organizational values can be used in the work that people do in the context of major organizational change. A key finding is that applying organizational values and convincing others to use organizational values at work can lead to better perceived work performance and satisfaction. We argued that a holonic interpretation of social and human development (Edwards, 2005; Wilber, 1999, 2000) serves to differentiate intentional, behavioral, social, and cultural development domains when using organizational values at work.

The four domains of development are important for a sustainable approach to organizational development and change. As such, the deliberate use or crafting of values is an important step towards better understanding and managing the motivational quality of organizational values in work environments characterized by proactive and innovative organizational change.

This is important because many organizations are currently facing the need to transform. The changing structure of individual and team work may thus require the fluidity that the crafting of organizational values can bring to organizational change efforts.

References

Adler, N. J., & Gundersen, A. (2007). International dimensions of organizational behavior: Cengage Learning.

Affleck, G., Zautra, A., Tennen, H., & Armeli, S. (1999). Multilevel daily process designs for consulting and clinical psychology: A preface for the perplexed. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 67(5), 746.

Amis, J., Slack, T., & Hinings, C. R. (2002). Values and organizational change. The Journal of Applied Behavioral Science, 38(4), 436-465.

Bakker, A. B., & Bal, M. P. (2010). Weekly work engagement and performance: A study among starting teachers. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 83(1), 189-206.

Bakker, A. B., & Demerouti, E. (2007). The job demands-resources model: State of the art. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 22(3), 309-328.

Bakker, A. B., & Demerouti, E. (2008). Towards a model of work engagement. Career Development International, 13(3), 209-223.

Bakker, A. B., & Sanz-Vergel, A. I. (2013). Weekly work engagement and flourishing: The role of hindrance and challenge job demands. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 83(3), 397-409.

Bakkerp, A. B. (2009). Building engagement in the workplace. The Peak Performing Organization, 50-72.

Bandura, A. (1969). Principles of behavior modification. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston.

Bansal, P. (2003). From issues to actions: The importance of individual concerns and organizational values in responding to natural environmental issues. Organization Science, 14(5), 510-527.

Baron, R. M., & Kenny, D. A. (1986). The moderator–mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51(6), 1173-1182.

Bass, B. M., & Avolio, B. J. (1993). Transformational leadership and organizational culture. Public Administration Quarterly, 17(1), 112-121.

Bateman, T. S., & Organ, D. W. (1983). Job satisfaction and the good soldier: The relationship between affect and employee “citizenship”. Academy of Management Journal, 26(4), 587-595.

Bauman, R., & Briggs, C. L. (1990). Poetics and performances as critical perspectives on language and social life. Annual Review of Anthropology, 19(1), 59-88.

Beauregard, T. A. (2011). Direct and indirect links between organizational work–home culture and employee well‐being. British Journal of Management, 22(2), 218-237.

Berg, J. M., Dutton, J. E., & Wrzesniewski, A. (2013). Job crafting and meaningful work. In B. J. Dik, Z. S. Byrne and M. F. Steger (Eds.), Purpose and meaning in the workplace (pp. 81-104). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Binnewies, C., Sonnentag, S., & Mojza, E. J. (2009). Daily performance at work: Feeling recovered in the morning as a predictor of day-level job performance. Journal of Organizational Behavior: The International Journal of Industrial, Occupational and Organizational Psychology and Behavior, 30(1), 67-93.

Bolger, N., Davis, A., & Rafaeli, E. (2003). Diary methods: Capturing life as it is lived. Annual Review of Psychology, 54(1), 579-616.

Brown, M. E., & Treviño, L. K. (2009). Leader–follower values congruence: Are socialized charismatic leaders better able to achieve it? Journal of Applied Psychology, 94(2), 478-490.

Cacioppe, R., & Edwards, M. (2005). Seeking the Holy Grail of organisational development: A synthesis of integral theory, spiral dynamics, corporate transformation and action inquiry. Leadership & Organization Development Journal, 26(2), 86-105. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1108/01437730510582536.

Cacioppep, R., & Edwards, M. (2005b). Seeking the Holy Grail of organisational development: A synthesis of integral theory, spiral dynamics, corporate transformation and action inquiry. Leadership and Organization Development Journal, 26(2), 86-105.

Cacioppes, R., & Edwards, M. G. (2005a). Adjusting blurred visions: A typology of integral approaches to organisations. Journal of Organizational Change Management, 18(3), 230-246.

Carey, J. W. (1989). A cultural approach to communication. Communication as culture: Essays on media and society. Boston: Unwin Hyman.

Carey, J. W. (2008). Communication as culture, revised edition: Essays on media and society. New York: Routledge.

Carlisle, Y., & Baden-Fuller, C. (2004). Re-applying beliefs: An analysis of change in the oil industry. Organization Studies, 25(6), 987-1019.

Carter, S., & Mankoff, J. (2005). When participants do the capturing: The role of media in diary studies. Paper presented at the Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems. ACM.

Cha, S. E., & Edmondson, A. C. (2006). When values backfire: Leadership, attribution, and disenchantment in a values-driven organization. The Leadership Quarterly, 17(1), 57-78.

Chen, G., Gully, S. M., & Eden, D. (2001). Validation of a new general self-efficacy scale. Organizational Research Methods, 4(1), 62-83.

Chomsky, N. (1986). Knowledge of language: Its nature, origin, and use: Greenwood Publishing Group.

Chomskye, N. (2005). Three factors in language design. Linguistic Inquiry, 36(1), 1-22.

Dekas, K. H., Bauer, T. N., Welle, B., Kurkoski, J., & Sullivan, S. (2013). Organizational citizenship behavior, version 2.0: A review and qualitative investigation of OCBs for knowledge workers at Google and beyond. Academy of Management Perspectives, 27(3), 219-237.

Demerouti, E., Bakker, A. B., Nachreiner, F., & Schaufeli, W. B. (2001). The job demands-resources model of burnout. The Journal of Applied Psychology, 86(3), 499-512.

Doughty, H. A., & Rinehart, J. W. (2004). Employee empowerment: Democracy or delusion. The Innovation Journal: The Public Sector Innovation Journal, 9(1), 1-24.

Dummett, M. A. (1993). The seas of language. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Edwards, M. G. (2005). The integral holon: A holonomic approach to organisational change and transformation. Journal of Organizational Change Management, 18(3), 269-288.

Fanelli, A., & Misangyi, V. F. (2006). Bringing out charisma: CEO charisma and external stakeholders. Academy of Management Review, 31(4), 1049-1061.

Fricker, R. D., & Schonlau, M. (2002). Advantages and disadvantages of Internet research surveys: Evidence from the literature. Field Methods, 14(4), 347-367.

Fuller, J. B., Hester, K., Barnett, T., Frey, L., Relyea, C., & Beu, D. (2006). Perceived external prestige and internal respect: New insights into the organizational identification process. Human Relations, 59(6), 815-846.

Garud, R., & Gehman, J. (2012). Metatheoretical perspectives on sustainability journeys: Evolutionary, relational and durational. Research Policy, 41(6), 980-995.

Garud, R., Gehman, J., & Kumaraswamy, A. (2011). Complexity arrangements for sustained innovation: Lessons from 3M Corporation. Organization Studies, 32(6), 737-767.

Gherardi, S. (2006). Organizational knowledge: The texture of workplace learning. Malden, MA: Blackwell.

Givón, T. (1993). English grammar: A function-based introduction (Vol. 2): John Benjamins Publishing.

Hackman, J. R., & Oldham, G. R. (1980). Work redesign. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley.

Halbesleben, J. R., & Wheeler, A. R. (2008). The relative roles of engagement and embeddedness in predicting job performance and intention to leave. Work & Stress, 22(3), 242-256.

Hannan, M. T., & Freeman, J. (1984). Structural inertia and organizational change. American Sociological Review, 49(2), 149-164.

Harter, J. K., Schmidt, F. L., & Hayes, T. L. (2002). Business-unit-level relationship between employee satisfaction, employee engagement, and business outcomes: A meta-analysis. Journal of Applied Psychology, 87(2), 268-279.

Hobfoll, S. E. (2002). Social and psychological resources and adaptation. Review of General Psychology, 6(4), 307-324.

Holloway, S. S., van Eijnatten, F. M., Romme, A. G. L., & Demerouti, E. (2016). Developing actionable knowledge on value crafting: A design science approach. Journal of Business Research, 69(5), 1639-1643.

Holloway, S. S., van Eijnatten, F. M., & van Loon, M. (2011). Value crafting: A tool to develop sustainable work based on organizational values. Emergence: Complexity and Organization, 13(4), 18-36.

Hollowaye, S. S. (2014). Value crafting: Using organizational values for the development of sustainable work organizations. PhD Thesis. University of Technology, Eindhoven.

Hox, J. (2002). Multilevel analysis: Techniques and applications. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

Itkonen, E. (1978). Grammatical theory and metascience: A critical investigation into the methodological and philosophical foundations of" autonomous" linguistics (Vol. 5). Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing.

Jayaseelan, K. A. (1993). Formal and functional explanations in linguistics. In S. K. Verma and V. Prakasm (Eds), New Horizons in Functional Linguistics (pp. 1-15). Hyderabad: Booklinks Corporation.

Joensson, T. (2008). A multidimensional approach to employee participation and the association with social identification in organizations. Employee Relations, 30(6), 594-607.

Judge, T. A., Bono, J. E., & Locke, E. A. (2000). Personality and job satisfaction: The mediating role of job characteristics. Journal of Applied Psychology, 85(2), 237-249.

Kerssens-van Drongelen, I. (2001). The iterative theory-building process: rationale, principles and evaluation. Management Decision, 39(7), 503-512.

Kira, M., van Eijnatten, F. M., & Balkin, D. B. (2010). Crafting sustainable work: Development of personal resources. Journal of Organizational Change Management, 23(5), 616-632.

Kraatz, M. S., Ventresca, M. J., & Deng, L. (2010). Precarious values and mundane innovations: Enrollment management in American liberal arts colleges. Academy of management Journal, 53(6), 1521-1545.

Larsen, R. J., & Kasimatis, M. (1990). Individual differences in entrainment of mood to the weekly calendar. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 58(1), 164-171.

Mathieu, J. E., & Taylor, S. R. (2007). A framework for testing meso‐mediational relationships in organizational behavior. Journal of Organizational Behavior: The International Journal of Industrial, Occupational and Organizational Psychology and Behavior, 28(2), 141-172.

McCullough, M. E., Bono, G., & Root, L. M. (2007). Rumination, emotion, and forgiveness: Three longitudinal studies. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 92(3), 490-505.

Miller, V. D., Johnson, J. R., & Grau, J. (1994). Organizational change. Journal of Applied Communication Research, 22, 59-80.

Nagy, M. S. (2002). Using a single-item approach to measure facet job satisfaction. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 75(1), 77-86.

Nicolini, D. (2011). Practice as the site of knowing: Insights from the field of telemedicine. Organization Science, 22(3), 602-620.

Ogbonna, E., & Harris, L. C. (2000). Leadership style, organizational culture and performance: Empirical evidence from UK companies. International Journal of Human Resource Management, 11(4), 766-788.

Ohly, S., & Fritz, C. (2010). Work characteristics, challenge appraisal, creativity, and proactive behavior: A multi‐level study. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 31(4), 543-565.

Ohlys, S., Sonnentag, S., Niessen, C., & Zapf, D. (2010). Diary studies in organizational research: An introduction and some practical recommendations. Journal of Personnel Psychology, 9(2), 79-93.

Pandey, P. (2004). Formal and functional aspects of phonological knowledge. In: R. K. Agnihotri et. al. (Eds.). Paper presented at the Proceedings of: The International Seminar on the Construction of Knowledge. Udaypur: Vidya Bhavan.

Pettigrew, A. M., Woodman, R. W., & Cameron, K. S. (2001). Studying organizational change and development: Challenges for future research. Academy of Management Journal, 44(4), 697-713.

Piccolo, R. F., & Colquitt, J. A. (2006). Transformational leadership and job behaviors: The mediating role of core job characteristics. Academy of Management Journal, 49(2), 327-340.

Pierce, J. L., Gardner, D. G., Cummings, L. L., & Dunham, R. B. (1989). Organization-based self-esteem: Construct definition, measurement, and validation. Academy of Management Journal, 32(3), 622-648.

Pitariu, A. H., & Ployhart, R. E. (2010). Explaining change: Theorizing and testing dynamic mediated longitudinal relationships. Journal of Management, 36(2), 405-429.

Preacher, K. J., Zyphur, M. J., & Zhang, Z. (2010). A general multilevel SEM framework for assessing multilevel mediation. Psychological Methods, 15(3), 209.-233.

Rhoades, L., & Eisenberger, R. (2002). Perceived organizational support: A review of the literature. Journal of Applied Psychology, 87(4), 698-714.

Robbins, S. P., & Coulter, M. K. (2002). Management (7th ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Salanova, M., Agut, S., & Peiró, J. M. (2005). Linking organizational resources and work engagement to employee performance and customer loyalty: The mediation of service climate. Journal of Applied Psychology, 90(6), 1217-1227.

Scandura, T. A., Graen, G. B., & Novak, M. A. (1986). When managers decide not to decideautocratically: An investigation of leader–member exchange and decision influence. Journal of Applied Psychology, 71(4), 579-584.

Schatzki, T. R. (2002). The site of the social: A philosophical account of the constitution of social life and change. University Park, PA: Pennsylvania State University Press.

Schaufeli, W. B., & Bakker, A. B. (2003). Utrecht work engagement scale: Preliminary manual. Utrecht, Utrecht University. Occupational Health Psychology Unit.

Schaufeli, W. B., & Bakker, A. B. (2010). Defining and measuring work engagement: Bringing clarity to the concept. In A. B. Bakker and M. P. Leiter (Eds.), Work engagement: A handbook of essential theory and research (pp. 10–24). New York: Psychology Press.

Schaufeli, W. B., Bakker, A. B., & Salanova, M. (2006). The measurement of work engagement with a short questionnaire a cross-national study. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 66(4), 701-716.

Schaufeli, W. B., Salanova, M., González-Romá, V., & Bakker, A. B. (2002). The measurement of engagement and burnout: A two sample confirmatory factor analytic approach. Journal of Happiness Studies, 3(1), 71-92.

Schwarzer, R., & Jerusalem, M. (1995). Generalized self-efficacy scale (pp. 35–37). In J. Weinman, S. Wright, and M. Johnston (Eds.), Measures in health psychology: A user’s portfolio. Causal and control beliefs. Windsor, UK: NFER-NELSON.

Seevers, B. S. (2000). Identifying and clarifying organizational values. Journal of Agricultural Education, 41(3), 70-79.

Selig, J. P., & Preacher, K. J. (2008). Monte Carlo method for assessing mediation: An interactive tool for creating confidence intervals for indirect effects. Computer software.

Sonnentag, S. (2003). Recovery, work engagement, and proactive behavior: A new look at the interface between nonwork and work. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(3), 518-528.

Suddaby, R., Elsbach, K. D., Greenwood, R., Meyer, J. W., & Zilber, T. B. (2010). Organizations and their institutional environments—bringing meaning, values, and culture back in: Introduction to the special research forum. Academy of Management Journal, 53(6), 1234-1240.

Tennen, H., Suls, J., & Affleck, G. (1991). Personality and daily experience: The promise and the challenge. Journal of personality and social psychology, 59(3), 313-337.

Totterdell, P., Wood, S., & Wall, T. (2006). An intra‐individual test of the demands‐control model: A weekly diary study of psychological strain in portfolio workers. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 79(1), 63-84.

Van de Ven, A. H., & Huber, G. P. (1990). Longitudinal field research methods for studying processes of organizational change. Organization Science, 1(3), 213-219.

Wanous, J. P., Reichers, A. E., & Hudy, M. J. (1997). Overall job satisfaction: How good are single-item measures? Journal of Applied Psychology, 82(2), 247-252.

Weber, P. S., & Weber, J. E. (2001). Changes in employee perceptions during organizational change. Leadership and Organization Development Journal, 22(6), 291-300.

White, J. K., & Ruh, R. A. (1973). Effects of personal values on the relationship between participation and job attitudes. Administrative Science Quarterly 18(4), 506-514.

Wilber, K. (1999). Integral psychology: Transformations of consciousness; selected essays. Boston, MA: Shambhala Publications, 4.

Wilber, K. (2000). A theory of everything: An integral vision for business, politics, science, and spirituality. Boston, MA: Shambhala Publications.

Wrzesniewski, A., & Dutton, J. E. (2001). Crafting a job: Revisioning employees as active crafters of their work. Academy of Management Review, 26(2), 179-201.

Xanthopoulou, D., Baker, A. B., Heuven, E., Demerouti, E., & Schaufeli, W. B. (2008). Working in the sky: A diary study on work engagement among flight attendants. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 13(4), 345-356.

Xanthopoulou, D., Bakker, A. B., Demerouti, E., & Schaufeli, W. B. (2007). The role of personal resources in the job demands-resources model. International Journal of Stress Management, 14(2), 121-141.

Xanthopoulou, D., Bakker, A. B., Demerouti, E., & Schaufeli, W. B. (2009). Reciprocal relationships between job resources, personal resources, and work engagement. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 74(3), 235-244.

Yeo, G. B., & Neal, A. (2006). An examination of the dynamic relationship between self-efficacy and performance across levels of analysis and levels of specificity. Journal of Applied Psychology, 91(5), 1088-1101.

Zueva-Owens, A., Fotaki, M., & Ghauri, P. (2012). Cultural evaluations in acquired companies: Focusing on subjectivities. British Journal of Management, 23(2), 272-290.